“From time immemorial, the circle with its four directions and unifying center has been a cosmic allegory,” writes Lama Tsultrim Allione. In her new book Wisdom Rising: Journey into the Mandala of the Empowered Feminine, the American teacher dives deeply into circles. She is specifically interested in the Mandala of the Five Dakinis, a Tibetan Buddhist image and practice. While intended for female-identified Buddhists who want to reconnect with the sacred feminine, the book also functions as an introduction to mandala practice. With in-depth psychological insight, narratives from Lama Tsultrim’s life, and guided meditations on the sacred mandala, Wisdom Rising skillfully connects an ancient, female-centered idea with the modern day.

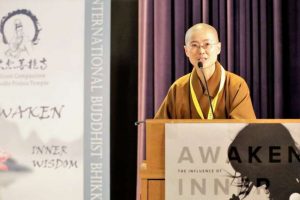

Lama Tsultrim Allione is no stranger to dakini meditation. Recognized as the emanation of Machig Labdrön, the 11th-century Tibetan dakini, she was one of the first Western women to be ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist nun. She founded Tara Mandala, a retreat center in Colorado, and often teaches on dakini practice. Her book Women of Wisdom, published in 2000, profiles six female Tibetan mystics, and she has written extensively on women’s roles in Buddhism, as well as how motherhood, family, and relationships interact with spiritual seeking.

While the dakinis certainly embody a feminine principle in Tibetan Buddhism, they are hardly definable as women. In her latest book, Lama Tsultrim writes that a dakini, sometimes called a sky dancer, is a “feminine energy that enters emptiness, moving through it, a messenger of it.” Often portrayed as fierce figures wielding curved knives and cups of blood, the dakini have the power to cut through illusion. For Lama Tsultrim, dakinis are deeply connected to a particular mandala of the Five Buddha Families, and are embodiments of the fierce, female presence in Buddhism. “When we can embrace her . . . she becomes our greatest ally. She becomes a compassionate support, a refuge, and a mother, but she will tolerate no self-clinging, no egocentric fixation, and she is never deceived,” writes Lama Tsultrim. In other words, the dakini becomes a way to identify where you’re feeling stuck and will help cut you free.

Do you have that friend who’s always busy, rushing around with their smartphone buzzing, striving to perfect their work project? She’s probably a karma family person. What about the relative who is prone to sharp, icy bursts of anger? She might need to work with the vajra dakini. In her book, Lama Tsultrim explains these two as members of the Five Buddha Families. Each “family” represents one section of the mandala, and the associated colors and qualities can be used as a focus for meditation and psychological work. Vajra, for example, is associated with blue, especially the icy blue of winter or the mirror-like wisdom of a mountain lake. Lama Tsultrim writes of the vajra dakini: “Her body is luminous blue and surrounded by wisdom flames . . . she is burning the transformation of anger into the mirror-like wisdom of clarity.” Through visualizing the dakini and her attributes in the mandala, practitioners can access that transformation as well.

The heart of the book is a guided meditation through the mandala itself. Lama Tsultrim helps the practitioner envision herself as a dakini of each family. The powerful practice helps the practitioner connect with blocked or damaged emotions, such as apathy, jealousy, and anger, and use the dakini visualizations to dissolve and transform those experiences. The mandala puts meditators in touch with the “ineffable power of the wild and the wise, the instinctive and sexual, the fierce power of the divine feminine,” Lama Tsultrim writes. This is no austere Zen breathing, but a colorful, complicated, psychologically-rich practice.

There is a psychological current in the book. Lama Tsultrim herself first encountered mandalas through C. G. Jung, and she braids his ideas into the Tibetan practices. Jung used mandalas in his psychological practice, believing them to be representations of the self. For Lama Tsultrim, however, the mandala represents a chance to reconnect with a vision of whole and empowered womanhood that is missing in modern times. She describes moments in her own life, such as after the loss of an infant daughter, when mandala practice helped her reconnect with the essential ground of existence.

By sketching profiles of people in each Buddha family, including how the person acts when embodying the “blocked” qualities and the “transformed” qualities of that family, Lama Tsultrim makes abstract concepts concrete and accessible. She situates each type of person in a party, describing their behavior: Do they go for the bar? Are they chatting up too many women at once? Are they hiding in the corner on their phone? Creating these playful psychological profiles makes each quality of the mandala seem real and recognizable, like friends you’ve encountered before. This technique also helps the reader identify which behaviors they see in themselves, and therefore identify which dakini to focus their practice on.

Grounding the book in 2018, Lama Tsultrim’s introduction gives the mandala practices a distinctly political flavor. She writes that she hopes practitioners can “respond with greater wisdom and effectiveness to the distress, challenges, and chaos of our global reality” after working with the dakini mandala. In particular, she draws parallels between sexual violence, the #MeToo movement, and global climate change, seeking a model for justice that uses feminine principles and empowers women’s voices. While she doesn’t spend much time on politics in the rest of the book, her introduction effectively situates the text as a response to modern times.