Image courtesy of the Pure Land Assembly

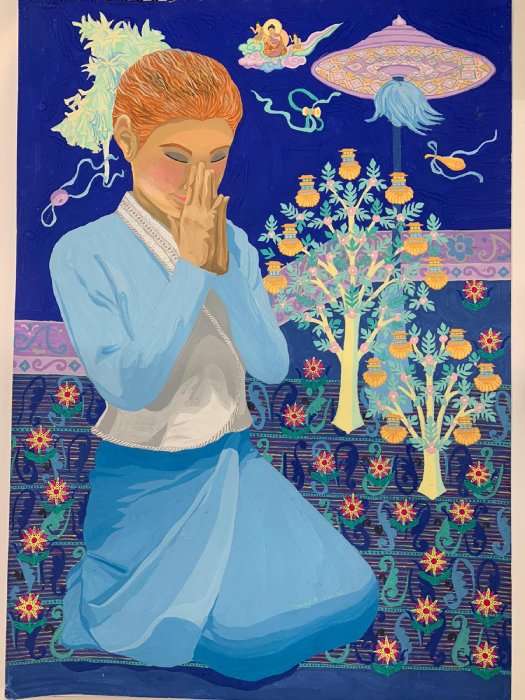

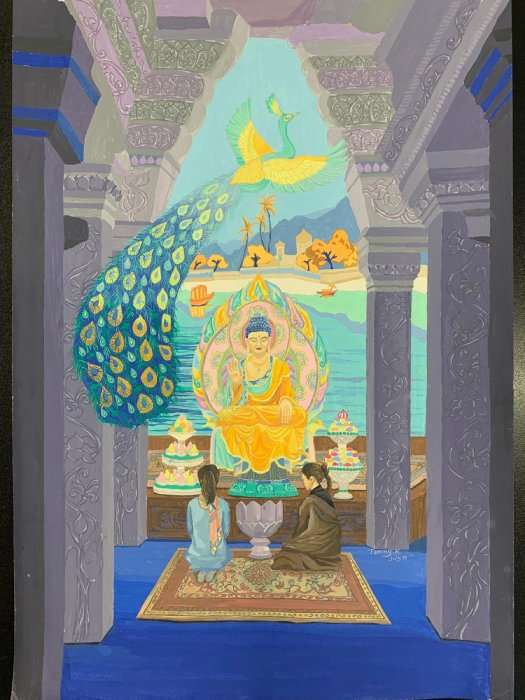

A pregnant woman caressing her swollen belly, which the viewer can sense is pulsing with life. Two ladies, one in laywomen’s robes, sitting in the ethereal hall of a Buddhist temple, heads bowed in contemplation before a shrine and Buddha image, while a phoenix, a creature representing rebirth, flies over them. A woman in meditative prayer, with a parasol and a flying cosmic Buddha on the backdrop. These beautiful pieces of art were painted by Tammy K. Ang, one of several artists trained in Western painting and invited to contribute three pieces of their work for a forthcoming book published by The Pure Land Assembly, a non-profit based in Hong Kong. The book and its accompanying exhibition in December are projects of the Pure Land Assembly team. We spoke to two leading members of the team about the book and exhibition: Ven. Dao Yuan, a young monk with a deep appreciation for the artistic, and Ng Yuen-wah, president of The Pure Land Assembly.

The book is an artistic homage to the bodhisattva Kshitigarbha (Dizang in Chinese, and Jizo in Japanese), whose name is commonly translated as Earth Store or Earth Womb. When it comes to iconography, Kshitigarbha appears as perhaps the most austere or “plain” of the four great Mahayana prime celestials (mahasattva), the others being Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, and Samantabhadra. Whereas these three bodhisattvas are concerned with cosmic compassion, depthless wisdom, and infinite good works respectively, Kshitigarbha’s Great Vow is concerned with freeing beings from the worlds below—the hell realms, a motif of considerable resonance with the Western Christian tradition.

“This is a fairly unique project because it collates art from a range of artists trained in expressionism, realism, impressionism, and so much more,” said Ven. Dao Yuan. “The book will be released in Chinese, English, and French. We hope to reach out to both Western and Asian audiences with this book, since Dizang is less known outside of the Sinophone world. Yet we’re confident that French-speaking audiences will appreciate the artistic emphasis on this bodhisattva, while English readers who already know something about Buddhism may find something new to appreciate in the Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva Pūrvapraṇidhāna Sūtra.”

Image courtesy of the Pure Land Assembly

In the Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva Pūrvapraṇidhāna Sūtra, the bodhisattva who would come to be reborn as Kshitigarbha was a young Brahman woman called Bright Eyes (Prabhacaksuh), who made a vow to save her mother from the hell realms. Her vow was, characteristically, ambitious and far-reaching.

“May my mother be liberated from hell forever. After the age of thirteen, to perform no more severe sins and not to undergo [any] evil realms (animal, preta – hungry ghost and hell). All Buddhas of ten directions, offer kindness and compassion on me, listen to me making this boundless vow on behalf of my mother: ‘If my mother can forever be liberated from the three evil realms and the low-class family or even be reborn as a female for eternal kalpas, I vow in front of the image of Pure-and-Clean-Lotus-Eyes Tathāgata. From today onwards, hundred thousand trillion kalpas in the future, all worlds that have hells and the three evil realms, those sinful suffering sentient beings, I vow to rescue them and liberate them from hells and evil realms, such as animal, preta – hungry ghost, etc. When such people with these sinful retributions have all reach Buddhahood, only then, I will attain ultimate enlightenment.” (Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva’s Initial Vows Sutra, The Pure Land Assembly translation, 67–69)

The realization of Bright Eyes’ Great Vows allowed the future bodhisattva, Kshitigarbha, to possess an array of enlightened activity that could “harrow” the hell realms from preventing sentient beings’ rebirth in the realms below to granting fortunate circumstances in this life.

“We asked 10 artists to take a look at passages of their choice in the Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva Pūrvapraṇidhāna Sūtra, and then allow their muse to guide them with whatever imagery or motif that might inspire them,” said Ng. “The specific artistic style was left up to the artist. We were confident that regardless of what the participants chose, the mother-child relationship and the idea of karmic destiny and being bound for hell would feel real to viewers, along with the compassion and sadness that arises when you put yourself in Bright Eyes’ shoes and know that your own mother is suffering in excruciating agony in hell.” This overwhelming compassion for the suffering endured in hell—which is described vividly in the sutra and also the subject of several artists in the upcoming book—is the source of Kshitigarbha’s vows and therefore his power. As the Buddha said:

“The mother of Prabhacaksuh is now Moksa (Liberation) Bodhisattva. The woman named Prabhacaksuh is now Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva. “Throughout these far long kalpas, [Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva] with such loving-kindness and compassion, [he has] made vows as many as sand grains of the Ganges River and guided numerous sentient beings. ‘In the future, if any men and women who does not practise wholesome deeds, who commit evil deeds, or even do not believe in the Law of Cause and Effect, who commit sexual misconduct, false speech, speeches that sabotage relationship, harsh speech, people who slander the Mahayana (the Great vehicle), etc., these sentient beings with such deeds will inevitably fall into the evil realms. However, if they encounter a learned friend who persuade them to take refuge to Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva, even for a moment as quick as the flick of a finger, such sentient beings will immediately liberate from the retributions of the three evil realms.’” (Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva’s Initial Vows Sutra, The Pure Land Assembly translation, 69–71)

Pregnancy, the glimpse of the transcendent, the mother-child relationship, these quintessentially human experiences famously hold unique power over the folklore of Chinese culture. The last phenomenon, the mother-child bond, became considerably “masculinized” over time: Kshitigarbha was a young woman when she made her Great Vow, an important point that would more appropriately fit a mother-daughter narrative. Yet literary tropes of the mother-son bond emerged in a particularly strong fashion in the Chinese context of a consolidated, Neo-Confucian, Song patriarchal political and cultural system.

This was not entirely by chance. Confucius was raised by his mother for much of his life as his father died when he was only three. He honored her for three years after her passing, establishing a custom of long mourning by sons for deceased mothers. Mother-son propriety and reciprocal love and loyalty were preoccupations of moral philosophers across China. It was precisely during the High Tang, in the seventh century, that the Tripitaka master and translator Sikṣananda provided a Chinese version of the Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva Pūrvapraṇidhāna Sūtra—it does not seem a coincidence that Kshitigarbha’s story resonates perhaps more viscerally with Chinese Buddhists than any other single story, including those of his peer bodhisattvas. Ng noted that the visual media of a book and an exhibition should help bring the motifs and stories within the sutra to life. “Not everyone pays attention to the Sanskrit or Chinese text, and not everyone knows where and how to access English translations,” she said. “Art, particularly of this professional, authentic quality, might be a different story.”

“This book and exhibition transcend any kind of sectarianism,” noted Ven. Dao Yuan. “It’s really about the condition of hell—whether physical and visual or mental and internal—and the rescue of the human condition. Hell and karma are both real, and I hope that this project can help people discern these metaphysical and moral realities.” In this sense, The Pure Land Assembly’s project is a visual accompaniment to the ancient sutra that gave humanity a glimpse into the misery and pain of hell. The suffering and karmic consequences are only half of the story. After all, it is Kshitigarbha’s harrowing of the hell realms that forms the conclusion of the sutra: “If wholesome men or wholesome women of the future have only one thought of respect for the Buddhadharma, I will use hundreds of thousands of skillful means to lead them to deliverance, so that they will be liberated from Saṃsara quickly.” (Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva’s Initial Vows Sutra, The Pure Land Assembly translation, 209)