Origami has evolved over the last few decades from a Japanese paper craft practiced mostly by children into an international pastime and a sophisticated form of artistic expression. In the last few decades, a number of artists around the world have been pushing the boundaries of origami by developing new folding techniques and styles and creating artworks that have transcended the world of craft to become a form of visual poetry.

One of these artists is Giang Dinh, from Vietnam, whose stylized figures of humans, animals, and faces are among the most lyrical and spiritual of all the origami artworks created today. In both the Zen-like simplicity of his folding style and the choice of Buddhist subjects for his work, we see in his origami figures a reverence for Buddhist ideals and beliefs that is rare in the often scientific and mathematical world of origami.

Born in 1966 in Hue in central Vietnam, Dinh spent his childhood there. Although not practicing Buddhists, he and his family did occasionally venerate the Buddha in their home, and he has memories of family friends who were Buddhist monks and of visits to pagodas when he was a child in Hue. Dinh studied architecture in Vietnam and moved to the United States in 1989, where he continued his architectural studies. He started creating origami in 1998, and for the last couple of decades has been working as an origami artist as well as an architect and painter. In all areas of his artistic work, he embraces simplicity and elegance. But it is in the realm of origami that Dinh is a true innovator.

Unlike most origami artists, who use thin, custom-made origami paper that can be folded many times, Dinh uses thicker paper such as watercolor paper, which is much harder to fold. However, once folded this heavier paper will hold the slightest fold and allows him to model semi-abstract forms that are at once simple and highly expressive. Dinh compares the crisp, sharp folds that define many origami sculptures to drawings rendered in ink. By choosing to softly—and sometimes only partially—fold his pieces, he instead evokes softer, subtler pencil lines.

Dinh’s origami style is highly admired by many in the origami community and beyond because of his ability to convey the essence of a creature or person in just a few gentle folds, in the same way that a Zen ink painting can depict the essence of a monk or a monkey in just a few well-placed brush strokes. Typically, Dinh works in plain white paper in order to concentrate on the pure form and shadow of the work. Many of his works are wet-folded, a technique developed in the mid-20th century that involves moistening the paper slightly in order to smooth down points and angles and create more naturalistic forms. Whereas many origami artists tend to fold animals, abstract forms, and geometric patterns, Giang Dinh has excelled in creating human figures engaged in dancing or praying, or even taking flight as angels. All of his works—his animals, humans, and deities—radiate a warm and gentle spirit that he seems to have released from the paper through the act of folding.

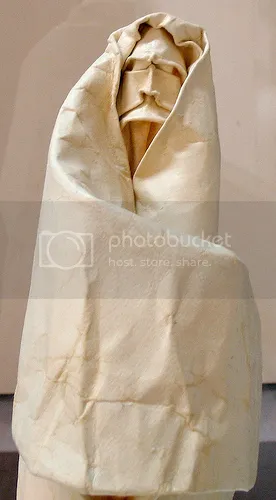

To describe his artistic process, he has quoted Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who wrote, “Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.” This perfection through simplicity is exquisitely apparent in his work Prayer, in which he employs a few simple folds to create the image of a robed figure praying, the most tightly folded element of the form being the hands clasped in prayer. “You can say that the simplicity aspect of my work is inspired by Zen’s art and philosophy. I love Haiku,” admits Dinh. However, he also points out other artistic influences. “I love the works of Brancusi, Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi . . .”

In another work, Dreamer, a semi-abstract figure is seated in the lotus position apparently in meditation, his whole form merging with, or perhaps emerging from, the ground on which he sits.

In some of his folded paper sculptures, Dinh depicts both actual and legendary Buddhist characters. Most well known is his Buddha, folded from cream-colored watercolor paper in the form of the head of the Buddha, recognizable by his ushnisha, or cranial protuberance, and his elongated earlobes, but without any facial details. This powerful faceless image reminds us of the Zen rejection of icons so that one will focus on the Buddha’s teachings. His figure of Bodhidharma, the patriarch of meditational Buddhism, is almost as mysterious, a tall form that is mostly hood, with a rugged face peering out from a single opening. Through expert folding, Dinh succeeds in conveying the sullen expression—complete with bulging eyes—that is often depicted in Zen paintings of this legendary teacher.

In another Buddhist piece, Bukan and Tiger, Dinh depicts the Chinese Chan master Feng Gan, seated on a mat with his pet tiger. Executed with a few simple folds in humble brown paper, the sculpture possesses the tenderness and humor that are typical of Zen portraiture in other media, including the ink paintings on which this piece was modeled. The sensitivity of his delicate folding here exemplifies Dinh’s brilliance as an origami artist and his deep affinity for the spiritual nature of the subject he is depicting. “I do read about Buddhism and Zen, and feel very close to Buddhism’s principal teaching,” explains Dinh. “I can imagine myself to be a Buddhist monk.”

More of Giang Dinh’s work can be found at his website giangdinh.

Meher McArthur is an Asian art curator, writer, and educator based in Los Angeles. She has curated over 20 exhibitions on aspects of Asian art. Her publications include Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs and Symbols (Thames & Hudson, 2002), The Arts of Asia: Materials, Techniques, Styles (Thames & Hudson, 2005), and Confucius: A Biography (Quercus, London, 2010; Pegasus Books, New York, 2011).