Who is the person who desires life, who seeks days of goodness?

Guard your tongue from evil and your lips from deceitful speech.

Shun evil and do good; seek peace and pursue it.— Psalm 34

The meaning is not in the words,

yet it responds to the inquiring impulse.

— Master Tozan’s Song of the Jewel Mirror Samadhi

As I wrote in my previous column, in these contentious times our public and private words can wound or heal. The tone of public discourse today is shockingly harsh. Maybe this has always been the case in the United States. With open access to social media of all brands, poisonous words create their own kind of pandemic. The insult, lies, and bitterness rampant in media inevitably infect the way we speak to each other privately. Harsh speech is normalized before we even notice it, creeping into the most intimate of exchanges.

When we speak unskillfully, our words are arrows. Once released, an arrow cannot be called back. Where it strikes, there is a wound. Even where the best of intentions are at play, and where there has been some healing between people, we find scars. Intention and impact fit together “like front and back foot in walking.” We see this in our relationships, in society, and in the sangha.

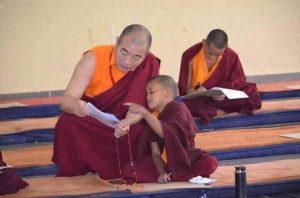

This is the core of engaged Buddhism—how we are in relationship to ourselves and to those around us in widening circles, systems, and societies. Speech and listening are the common coin of relationship. Buddhism, along with other faith traditions, has a lot to say about how we speak. In my previous article I addressed hearing and listening. This month I speak about speaking. Buddhism has clear practices of Right Speech (Pali: samma vacca) the third step on the Noble Eightfold Path. In the Pali Canon (SN 45.8), the Buddha mentions four qualities of Right Speech:

. . . what is right speech? Abstaining from lying, from divisive speech, from abusive speech, & from idle chatter: This is called right speech.

Three of the 10 bodhisattva precepts warn about harmful speech—precepts 4, 6, and 7:

I vow to refrain from false speech.

I vow not to slander.

I vow not to praise self at the expense of others.

Thich Nhat Hanh folds these into his Fourth Mindfulness Training: “Deep Listening and Loving Speech.”

Aware of the suffering caused by unmindful speech and the inability to listen to others, I vow to cultivate loving speech and deep listening in order to bring joy and happiness to others and to relieve others of their suffering. Knowing that words can create happiness or suffering, I vow to learn to speak truthfully, with words that inspire self-confidence, joy, and hope. I am determined not to spread news that I do not know to be certain, and not to criticize or condemn things of which I am not sure. I will refrain from uttering words that can cause division or discord, or that can cause the family or the community to break. I will make all efforts to reconcile and resolve all conflicts, however small.

Arising from the silence of meditation, inevitably we have to say something. We will say something, even if we write it in a note or speak with gestures. Again, the Buddha instructs us about what kind of words are appropriate. He advises us to speak words that are true, useful, timely, and beneficial or motivated by loving-kindness.

Now, a buddha, with powers of omniscience, would not have to guess about these qualities—his or her insight would be sufficient. But for those of us aspiring to the Buddha Way here in samsara, these four conditions of speech can be elusive. If I know my friend well, I might be able to make a good guess about what she might receive as true, useful, timely, and beneficial. And I might guess wrong. If I am speaking with someone I don’t know or with whom I already have conflict, it is likely we will disagree on one or more of these points.

So, is there ever a right time to speak? Are words ever completely true? When we speak, we take a leap into the unknown, and that is okay. It is no different from anything else we do. It is important to clarify our intentions as best we can. Still, we cannot know the impact of our words until they have been spoken and heard. Intention and impact are interdependent. Perhaps silence is better. But there is so much joy and connection in the play of words. I can’t easily give up such human pleasure.

I leave you with a recommendation: we can learn to ask questions before making assertions. Sometimes I might lose myself in the assertion of “my truth.” I’m not alone in that habit. Better to ask questions and create dialogue, remembering that the meaning “responds to the inquiring impulse.” Try it out.

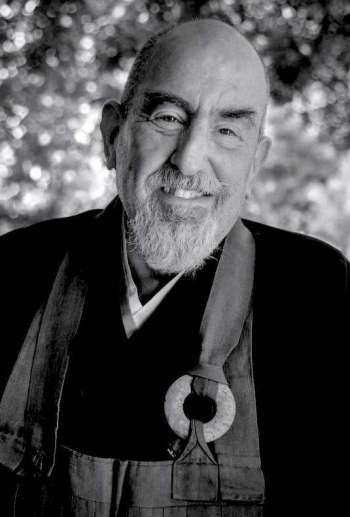

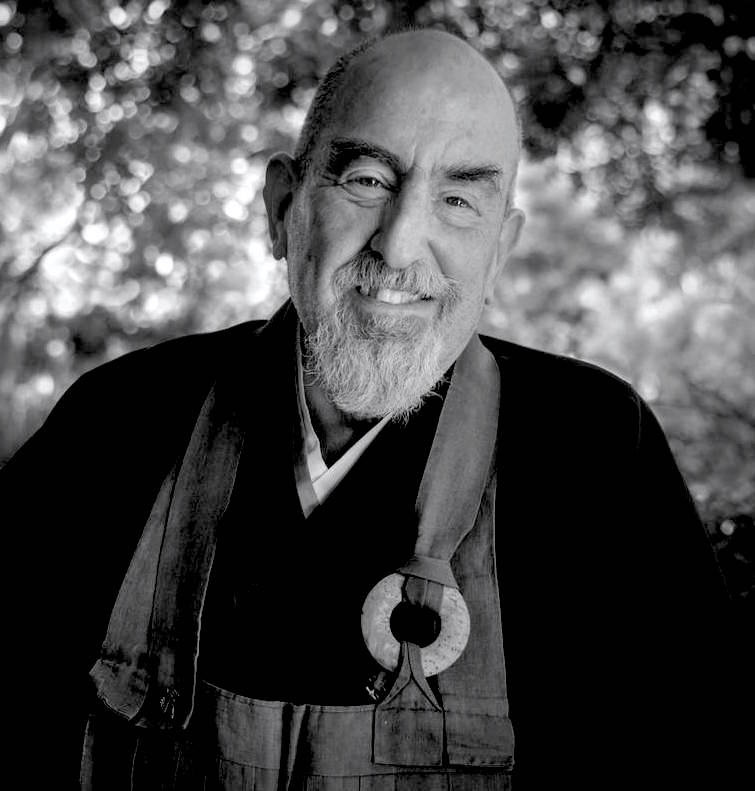

Hozan Alan Senauke

Berkeley, California

January 2022

See more

Berkeley Zen Center

Clear View Project

International Network of Engaged Buddhists

Related features from BDG

Right Speech is Responsible Speech

The Two Bright Guardians of the World

Buddhistdoor View: How Bad Faith and Dissembling Threaten Prospects for Peace

The Foundation of Communication and Leadership