The British Library held a conference titled “Unlocking Buddhist Written Heritage” from 7–8 February this year, bringing together scholars from around the world to examine Buddhist texts and manuscripts through the lens of collections. This conference was held in partnership with The School of Oriental and African Studies and supported by the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation. The British Library team is presently releasing a series of recordings of the speakers’ presentations, with full audio and slide visuals available on the British Library YouTube playlist. The second lecture to be uploaded is Dr. Jann Ronis’ speech about the Buddhist Digital Resource Centre (BDRC), of which he is executive director.

This is a special year for BDRC. Already a well known and trusted resource for Buddhists, scholars, and translators worldwide, the organization is engaged in digital cultural preservation projects across Buddhist Asia (specifically, Cambodia, China, Mongolia, Nepal, and Thailand). Having recently reached the 20th anniversary of its launch in 1999 as the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center, Dr. Ronis’ speech highlighted the history and projects of BDRC and how they relate to the themes of collections and collaboration.

First, Dr. Ronis invoked Indra’s Net, which appears in the Avatamsaka Sutra and visually represents the objective of BDRC: connecting Buddhist literature with the world at all levels. Its methodology broadly encompasses being involved in preservation projects across Buddhist Asia, making Buddhist literature accessible, and drawing connections between the literature and the wider world. This motto has two elements: first, BDRC aims to digitally articulate the deep connections already existing between the texts of the Buddhist corpus—coding into software the philological, philosophical, and historical relationships between bodies of Buddhist literature. Furthermore, the organization’s content creation must serve a general audience and not just specialists.

After a tribute to the life of Gene Smith (1936–2010), the founder of the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center and therefore of BDRC (the organization finalized its name change in 2016), Dr. Ronis went on to discuss various digitization projects, non-Tibetan as well as Tibetan. The scale of the latter has actually been upgraded now that BDRC is able to operate in China, which holds the largest collections of Tibetan-language Buddhist texts in various research centers.

BDRC aspires to remain the leader of text digitization in Buddhist Asia. One of the first projects it conducted after its renaming was to scan 11,000 Burmese and Pali manuscripts in the library of Prof. Peter Skilling, one of the foremost experts on Theravada and Southeast Asian Buddhism. While the entire collection has been catalogued, few of the texts have been treated with any conservation methods. Therefore each folio must be washed, cleaned, re-inked, and oiled before it is ready for digitization. This is a project that requires a large team, and the texts are being scanned to a very high archival quality. In Cambodia, a year-long project has partially consisted of fieldwork, with the BDRC team going to village monasteries and requesting to borrow manuscripts to scan in Phnom Penh. BDRC has partnered with Digital Divide Data, a local Cambodian non-profit, to do the digitizing. Another collaboration is being done with Asian Classics Input Project at the National Library of Mongolia. Here, BDRC is scanning more than 40,000 volumes of the library’s Tibetan collection—double the BDRC’s entire present collection of Tibetan-language works. The cataloguing and digitization work has been meticulous while also making rapid progress.

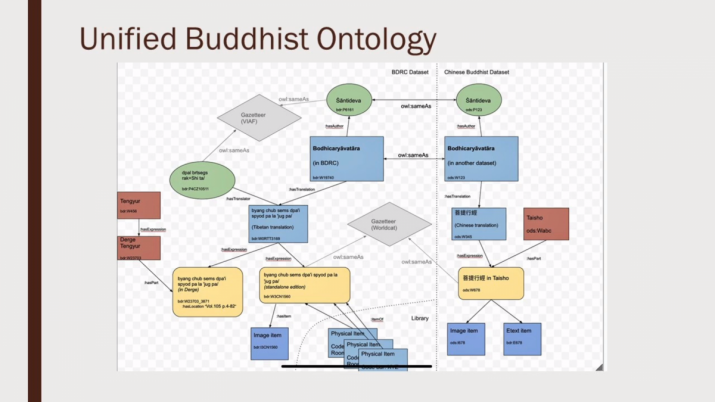

BDRC’s next-generation web platform of the Buddhist Universal Digital Archive (BUDA) was the final subject of Dr. Ronis’ speech. This software, developed in collaboration with Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China, and supported by the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation, was given the epithet a “Buddhist library for the information age.” It has three components: digitization work, a new ontology (a shared vocabulary to name entities by a community of scholars so that different databases can communicate with each other), and a versatile image viewer.

The new framework is called the Unified Buddhist Ontology, which facilitates open access and data sharing to accommodate Buddhism’s canonical and vernacular traditions. Dr. Ronis used the example of Shantideva’s Bodhicharyavatara to illustrate how BDRC’s ontology for this text connects with the Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association’s (CBETA) entry for the Bodhicharyavatara, using digital vocabulary to bridge the different parameters and languages of the databases.

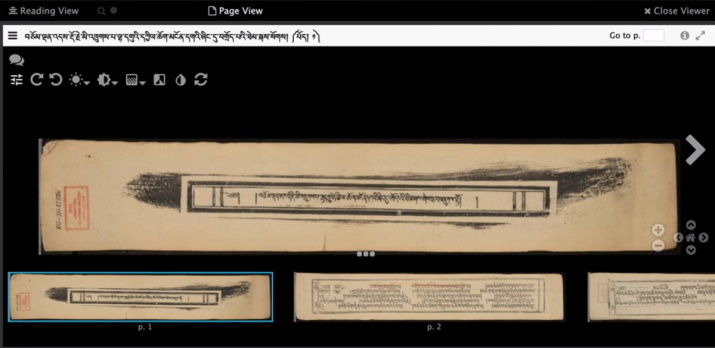

BUDA deploys a state-of-the-art image viewer, with a system called “international image inoperability framework” (IIIF). It provides full-screen viewing, scrolling, image manipulation tools, and precise linking, much like most image editors, but is also able to assemble and curate collections that are drawn from multiple libraries but organized within a single system. This means significantly improved sharing, perhaps the most expansive for a single system. Thanks to these capabilities, the entire Taisho Revised Tripitaka in Chinese script has been brought over onto BUDA’s website. The images can be taken from elsewhere (in this case Japan) but integrated into BUDA’s own framework.

Technological breakthroughs like IIIF allow BDRC to serve the broader community in various ways. For example, institutions such as libraries or other educational institutes no longer need to build and maintain their own archives. In Mongolia and Cambodia, BDRC demonstrated to the countries’ respective culture ministries that it was not scanning texts in an “extractive” way. Instead, BUDA helped BDRC create localized websites in the local language. These websites seamlessly provide all of the scanned texts as a complete archive for fully localized use. It can be used as a high-standard and free (or at minimal cost) reference, without the need to purchase, maintain, and upgrade all of the necessary and expensive equipment. One user of this reference material is none other than the Dzongsar Khyentse Chokyi Lodro Institute, while another is the National Library of Mongolia itself.

Dr. Ronis concluded by identifying the four “pillars” of BDRC’s methodology: preserve, connect, amplify, and enable. Through its various programs (with BUDA perhaps being the most ambitious over the long term), BDRC maintains its position as a premier source for Buddhist texts and preserved material. It fulfils not just the calling of preservation, but of dissemination, and both through the method and technology of digitization. Despite the impressive volume of texts already digitally preserved on BDRC, there is a truly colossal collection of Buddhist scriptures that has not yet enjoyed the attention of BDRC. Some might be in private collections, others in government-funded archives, and others yet unearthed or forgotten. Dr. Ronis is confident that momentum can be maintained and that his organization’s work has only just begun.

See more

An Indra’s net of Dharma for the Information Age (YouTube)

The British Library (YouTube)