“Return to Amida, Return to Amida, So even dewdrops fall,” wrote the Soto Zen hermit Ryokan (1756–1831) famously, and throughout his life he exhorted those experiencing suffering, tribulation, and misery to do just that: to find refuge in the home of Amitabha Buddha. As a believer in Pure Land Buddhism, he knew that Amitabha would be waiting for him at the time of death. Amitabha awaits all beings’ return to him like wayward children to a parent, and when they do, he receives them lovingly, his hand outstretched in welcome.

Of course, such poetic love is not clearly expressed in the Pure Land sutras, which, despite their doctrinal eloquence and clarity, do not possess the kind of literary beauty offered by Japan’s poet-monks. Rather, Pure Land devotional imagery was nurtured in the artistic and aesthetic sensibilities of Chinese and Japanese painters. The motifs these artists imagined were original in concept, but earned their legitimacy through reference to images found in the Pure Land canon. My favorite example of this creativity is the device known as the “Descent of Amitabha” (Ch. Amituofo laiying tu 阿彌陀佛來迎圖; J. Amida raigo zu), which depicts Amitabha reaching out to the devotee to welcome her into his paradise at the moment of death.

The Descent of Amitabha is a distinct genre of Pure Land painting that arose after the appearance of “transformation” paintings (jingbian tu 經變圖 ) at Dunhuang, which give pictorial form to the Contemplation Sutra (Amitayurdhyana Sutra). A narrative-manual on visualizing Amitabha Buddha, the Contemplation Sutra tells the story of Queen Vaidehi’s imprisonment in her own son’s dungeon and the Buddha Shakyamuni’s instruction to help her visualize the Pure Land so that she may escape her world of despair. The mysterious artists of Dunhuang’s jingbian tu, as well as those working at Yulin and other cave sites, laid the foundation for “transforming” textual doctrines into visual reality. Dunhuang jingbian art functioned as an aid for meditation, articulating Queen Vaidehi’s story in the Contemplation Sutra while assisting the meditator in visualizing the Pure Land’s wonders—from the pavilions and saintly residents to the splendid sambhogakaya forms of Amitabha and his attendant bodhisattvas, Avalokiteshvara and Mahasthamaprapta.

One could say that with the jingbian paintings, one already finds oneself in Amitabha’s paradise. Conversely, artworks depicting Amitabha escorting the dead to this paradise may not initially have seemed to be glorious visions. But artists soon came to see this format as more intimate and depicting something that the more “august” and “magisterial” Dunhuang cave art could not: the loving, personal encounter between Amitabha and his devotee, a religious vision that rapidly gained in popularity.

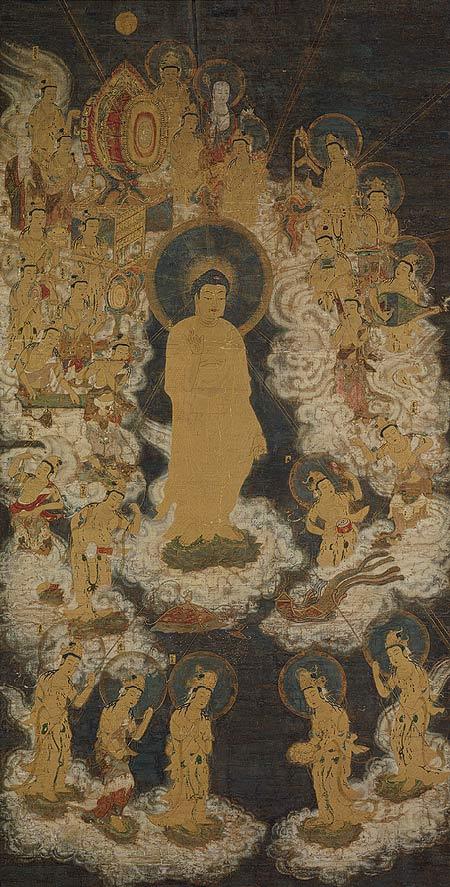

This slightly more varied and creative genre, not widely produced in China until the 12th to 14th century, was a distinct way of envisioning a deceased devotee’s meeting with the Buddha of Infinite Light. The welcome that Amitabha and his host of attendant bodhisattvas give to beings entering the Pure Land is called laiying 來迎 in Chinese (J. raigo). The Pure Land devotee’s faith rewards him with the guarantee of Amitabha’s 19th vow, the vow second in importance only to the 18th. This vow promises that sentient beings who establish the Bodhi Mind (to develop the aspiration for enlightenment), accomplish merit, sincerely aspire to attain Enlightenment, and desire to be reborn in his paradise will see Amitabha appear before them at death surrounded by a multitude of sages. In both Chinese and Japanese paintings, this assembly seems to consist of beings in princely robes and emanating divine light, indicating their status as bodhisattvas.

The simplest arrangement of the Descent genre simply depicts Amitabha standing in three-quarter view with his right hand outstretched, a stance unique to him. As seen in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Southern Song-era (1127–1279) Buddha Amitabha Descending from His Pure Land, the Buddha’s left hand remains in the more common meditation mudra (samahita, or dhyana, mudra; in later paintings he holds a lotus), while his outstretched right hand is in the welcome mudra (varada mudra).

Amitabha’s varada mudra is open and relaxed, and expresses delight at meeting the devotee. The hand is extended in an inviting and intimately personal gesture, urging the practitioner to take it so she can join Amitabha in his paradise. It is totally unlike any other mudra, most of which express a teaching, a virtue or, in the tantric traditions, a specific power. This is a mudra that is made for sentient beings, an expression of Amitabha’s relationship with them and of his unconditional love.

It is in Japan that that the Descent motif enjoyed more rapid development. After the Chinese Tang dynasty (618–907), Japan was no longer simply the recipient of Buddhist texts and art from China. The Fujiwara era (794–1160; named after the powerful regent family that provided courtiers and wives to the imperial clan) of the Heian period (794–1185) saw the consolidation of Pure Land Buddhism. Because of this, the

early 11th century witnessed a series of innovations that enriched and diversified the Descent aesthetic. Amitabha remained the central figure, but by referring to the 19th vow, Japanese artists found a unique opportunity to depict Avalokiteshvara and Mahasthamaprapta beside Amitabha (this is a motif that consistently appears throughout the Pure Land canon). This was known in Japanese painting and sculpture as the raigo triad, where one figure could not appear without the other two. For some artists, this inclusion logically extended to the entire host of sages that Amitabha vowed would appear with him at the devotee’s time of death.

We have the genius of Jocho (d. 1057) of the late Fujiwara to thank for the popularization and perfection of the raigo triad style. Jocho was a pioneering Japanese sculptor and painter who executed an early masterpiece of combined yamato-e (Tang dynasty-inspired classical Japanese art) and raigo imagery on the doors of the Phoenix Hall of the temple Hojo-ji in 1053. In Japan, seeing the raigo at death came to be associated with guaranteed enlightenment and rebirth in the Pure Land. It is still common for some Japanese households to have a raigo shrine, and a raigo painting is often presented to a person on their deathbed.

Another aesthetic innovation was the depiction of Amitabha and his attendants descending “over the mountains” (J. kenpon choshoku yamagoe amida zu), also perfected by Jocho. In these paintings, the trio speed over high mountains on clouds, appearing as colossal celestials behind the landscape to whisk the deceased away to the Pure Land. The Descent genre therefore came to consist of three formats: Amitabha alone, Amitabha with his bodhisattva attendants, and Amitabha with his whole entourage. However, we must be careful not to define this rich body of work as some kind of formal school. Rather than any hard and fast rules governing how the entourage or central triad should be depicted, the Descent genre seems to have been an organic, decentralized tradition. Despite its original fidelity to the imagery and doctrines within the Pure Land canon, artists eventually adopted what they felt to be most spiritually significant for Buddhist devotees.

The artistic encounter between savior and saved is best illustrated in the paintings that include the devotee, who looks up at the descending Buddha and his company with arms raised in prayer and gratitude. Depictions like these indicate not only Amitabha’s compassion and love, but also the “naturalness” of returning to his light. Just as Ryokan’s poem describes dewdrops going nowhere else but down, the sun can set nowhere else but in the west. So En’i (1118–90), using the fitting pen name Saigyo, literally “Journey to the West,” wrote:

Over the mountain edges

Slips the moon;

Watching it

I too enter

The west of my heart.

For the Pure Land devotee, she can be certain who will be waiting in the metaphysical west to welcome her home: none other than the Buddha of Infinite Light.