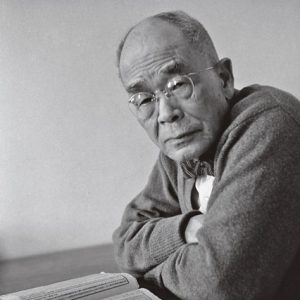

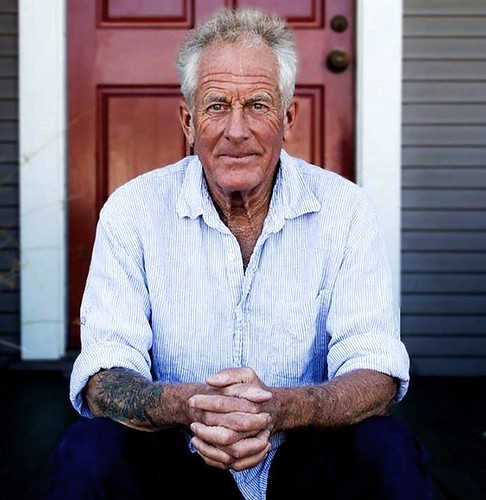

As a self-taught oxy-acetylene welder and former metal sculptor, I have a lifelong attraction toward steel and bronze, whether ground to brilliant perfection or left to rust, old and abandoned. As a meditator, I am drawn to the cultivation of awareness, what Buddhists call the view or awakening, a continual practice of returning again and again to this moment just as it is. I recently spent an enchanted afternoon with artist David Kimball Anderson at his home and studio in Santa Cruz, California, absorbing the simple beauty of our conversation, his wife Lis’s garden, and their giant black Labrador Luke. David generously shared his sculptures, works on paper, and some of the stories behind them, and we bonded over nature, metal, and the literal art of meditation.

As David says, there is a story, a reason, or a drive behind each piece. His practice through the work is to “to take foot off gas, put things in neutral, to realize a pause, quieting the chattering mind.” Long ago, a student of his was trekking in Nepal and came to Namche Village, where she became very sick. She needed to be sent, lashed on a pony, up a steep trail alone, then to be airlifted out to Kathmandu. David made a piece about the pony who carried her called Pony Trough, an ode to this hardworking creature. Another lovely work is cast aluminum cornice with some simple prayer flags, like a postcard from Namche. Though minimal, the gesture is evocative of place, meaning, devotion, lineage. Born from tradition, it bridges East and West, past and present.

The story behind Trungpa’s Ladder is from Born in Tibet, Chögyam Trungpa’s autobiography. In his account of fleeing the Communist invasion, Trungpa and many others fled over rough terrain for months. They came to a precipice over a river and needed to somehow get down the steep embankment in order to cross. They had to lash together long logs and then carve out stairs that were very tiny. Their entourage included some very old lamas, and everyone helped them make their way down this rickety ladder to a landing place in the river. Like much of David’s work, Trungpa’s Ladder is both straightforward and layered with meaning, both apparent and implied in the visceral experience. He lets the viewer enter to make their own connection.

David often finds appealing objects, either manmade or natural, and recreates them in iron and steel to enjoy their visual, tactile presence. David created a close replica of a water trough that he found far out in a cow pasture, complete with calcium deposits and errant wildflowers, all in steel. Relating to David’s sculptures and drawings has the satisfaction of reading Walt Whitman or Mary Oliver, or Basho with his sense of karumi, or lightness.

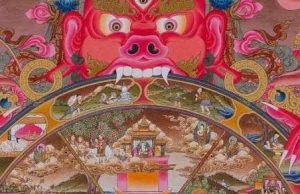

David’s subject matter moves fluidly between organic chemistry, the heavens, bodily energies and senses, nostalgia, emotion, time, and space. He takes inspiration from the immediate sensory world. Nature inspires him very much, as does old farm equipment, rusted steel fixtures, and religious articles. He shared that, “Where I surf in Santa Cruz there are concrete slabs, and where I walk in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, there are these rocks with great appeal. I participate with the image I create based on what I see from observation. I often photograph and then recreate in steel. The format is more modernist sculpture.” David’s references are many, including descansos, the New Mexican roadside shrines to the dead. Like Tibetan prayer wheels, or the religious items available in Rome, David enjoys objects and events that invite the public into spiritual experience. What he loves about the descansos in New Mexico is that on holidays, families come out to honor their dead, as in a wake. For him, spiritual practice includes not just meditation and mindfulness, or science and astronomy, but once again, active observation and thus participation.

In the middle of our walking conversation, we stopped together to rescue a bee on the sidewalk who was struggling, and moved it to safer place off the path. Observation, relating, leaning in, enacting meditation and compassion seamlessly in the flow of life.

David’s frequent refrain, “So, you see?” says it all. Taken as an invitation—to observe one’s mind, the outer world, and the spaces between—all inform his work as an observer, artist, and good human. His tools are space, form, color, composition, line, relationship, tone, shadow. “A lot of what I do is a process of enjoyment.” This kind of deep, affectionate involvement with phenomena is a key facet of meditation.

David recreated a concrete sink in the orchard, and a huge metal trough for watering livestock in the field, simply for the pleasure of creation and appreciation of the finished pieces. Many of his works are smaller vases with flowers; ikebana in steel and color. “These still lifes are a practice in pause and sensitivity. They are a combination of touch—from the works on paper, in two dimensions—to the observing pieces in three dimensions. These still life sculptures are my daily practice. They are so enjoyable for me to make.”

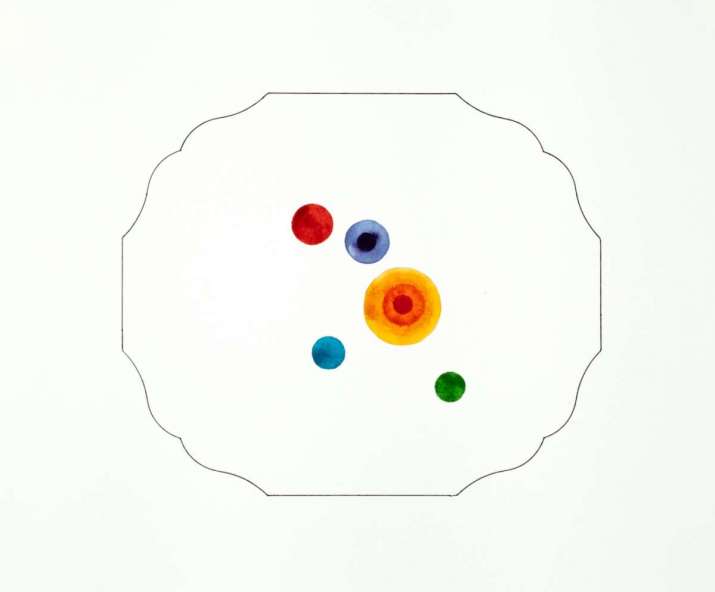

Bands, works on paper, are drawn from Peruvian shaman work with stones which are placed on areas of the body, creating energetic bands of color, centers from where power and protection are sourced, as well as connection or engagement. Not unlike depictions of chakras, as in the golden globe above the head, these drawings of auras or sources of vitality are accessed by visualization. There are very similar depictions across traditional cultures in many parts of the world.

Heat Points drawings explore the interplay of the erotic in touch, the heat points of male and female sensitivity – not a blatant but primary portrayal of this dynamic experience. Points of sensitivity and filaments are touch in the broader reference of organic chemistry. David’s approach is respectful, open, and sensitive in observing the sensual energies and tantric sensibilities of our rich human experience.

Nutrient Points are based on David’s first experience with acupuncture as a skeptic. Since it helped relieve his back pain, he was inspired to make these drawings, investigating and attempting to illustrate the meaningfulness and experience of mindfulness touch. David’s drawings are often more personal whereas his sculptures tend to be more observing and interpreting phenomena.

David sometimes juxtaposes form with emotions such as anger, as portrayed by an abstract, sharp triangular steel piece, meant to hang at eye level in a gallery without any protective barrier. Yet the pokey piece was suspended and lit up above a seated Buddha figure covered in silverleaf, a reminder perhaps of taking all emotions as the path.

David’s work immediately brings one home to the heart, to a feeling of true center and the straightforward beauty of unadulterated observation, like a satisfying conversation with the natural world, or another being. As Henry David Thoreau put it: “Every morning was a cheerful invitation to make my life of equal simplicity, and I may say innocence, with Nature herself.” David’s art is highly attuned to nature, to the life of feeling and enjoyment, and to the great mystery of being human on this Earth.

See more

David Kimball Anderson

DAVID KIMBALL ANDERSON: WORKS 1969-2017 (Radius Books)