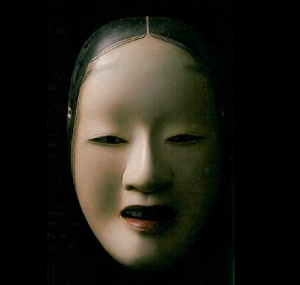

Japanese Noh is one of the world’s great performance forms. In Japan, Noh theater has continued since the 13th century as a living distillation of Japanese aesthetic sensibilities, and Samurai-era Zen Buddhist thinking about the afterlife. Noh’s founder, Zeami (pronounced zay-AH-mee) rose from the humble ranks of traveling performers in the 14th century to become the favorite of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, who educated him and provided opportunities for artistic uplift. In return, Zeami created Noh from the earlier art form sarugaku. Noh has attained a kind of artistic eternity thanks to the genius of Zeami, who brought Noh to epitomize classical artistic expression.

But Shogun Yoshimitsu’s son, Yoshimochi, who became the successor shogun, did not favor Zeami. The new shogun was not artistically inclined, and was accused of being unable to fathom Zeami’s sophistication—even by his own father. After Yoshimitsu died in 1408, Yoshimochi placed Zeami’s nephew as the headmaster of the Kanze school of Noh, against Zeami’s wishes. In 1434, Zeami—the most celebrated performer and playwright of the capital, Kyoto, and the favorite of Shogun Yoshimitsu—was exiled by Yoshimochi to Sado Island, known as the Isle of Exile. Two years later, still in exile, Zeami completed his final work, detailing his desolation with a spirit of acquiescence, fated karma, and gratitude for his father who gave him his art; and for Shogun Yoshimitsu, who favored and educated him. The end of Zeami’s life is shrouded in mystery. It is thought he was pardoned after some years and lived out his life as a Buddhist renunciate. Although Zeami was contemplative by nature, he was admired for his physical beauty as well as his artistic accomplishments. This exile is a tragic ending for the devoted artist who gave the world one of its loftiest arts.

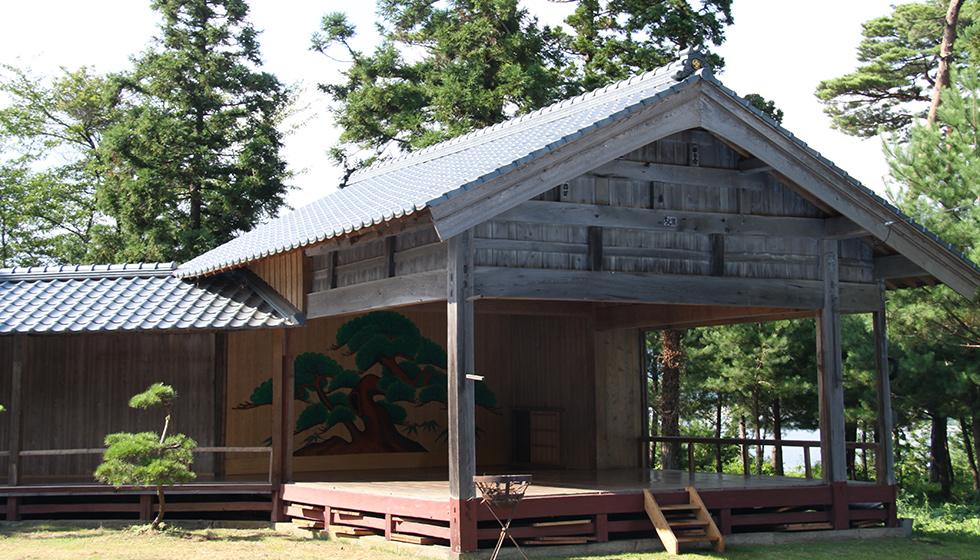

Sado, where Zeami was exiled, has, since his unjust punishment, celebrated Zeami’s life as few other places have. The island was known as the Island of Exile; and Zeami was not the first to be banished there. Sado, far north of Kyoto, off the western coast of Japan, was a lonely displacement from the bustling capital. Despite the notoriety of the island, Noh has come to be celebrated as a sacred trust on Sado, once boasting 200 Noh stages at its peak in the 16th century. Today, more than 30 old Noh stages still exist. It is an architectural feast that sheds light on earlier performance history that is difficult to find and share. This article features six of those 30 extant stages.

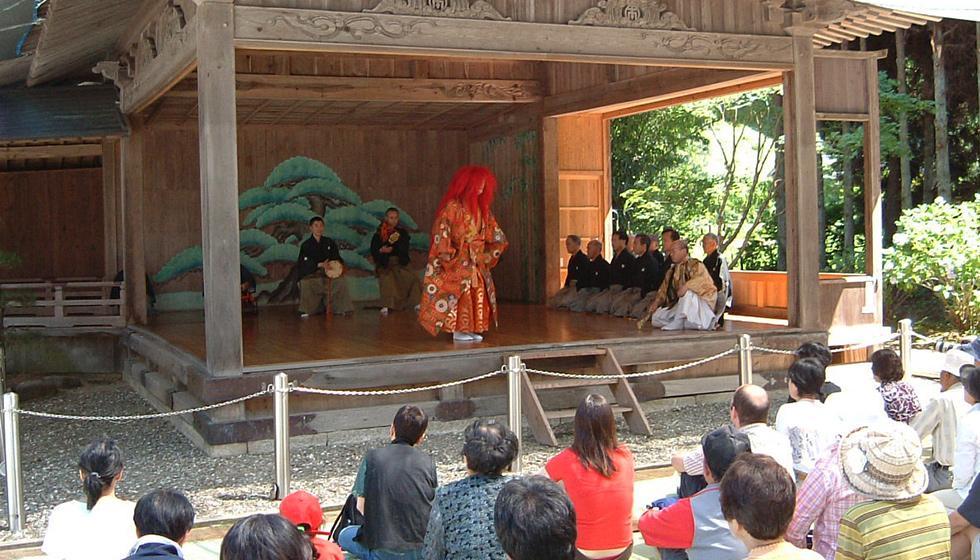

The back of the stage is a fixed panel on which is always painted a pine tree—the eternal setting of Noh, evoking the Yōgō pine tree at Kasuga Shrine in Nara, where Noh has been performed since its earliest manifestion as sarugaku in the 12th and 13th centuries. The pine panel is called a “mirror-wall,” as if the performance was facing the god (kami) who inhabits the sacred pine tree. Noh evolved from traveling performances to dramas danced on specific outdoor stages, both temporary and permanent. It was not performed indoors until the late 19th century. Living pine trees are set along the entrance walkway, along which characters move from one world to the next.

Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples alike supported Noh by sponsoring performances on their grounds since as early as the sixth century. It was common until the Meiji era (1868–1912) for temples and shrines to share the same grounds as both a shrine and a temple, both Shinto and Buddhist. Buddhist architecture, having Chinese influences, impacted Shinto shrine architecture, which had hitherto demarcated sacred places, spots, and natural entities, such as waterfalls, boulders, and trees, but not always with a permanent structure for ritual practice. Noh itself is inspired by Shinto ritual dances for priestesses (Jp: miko), which had no narrative content, and were “all space”—a kind of danced emptiness, a ceremonial ritual movement designed to suit higher beings. Noh was also transformed by Buddhism, adopting a Buddhist structure of the afterlife, as souls seek to escape the Wheel of Life and Death, and attain enlightenment. Shinto had no such developed concepts of the afterlife.

The Noh stages on Sado were historically on grounds that were both Shinto and Buddhist: it was common to see a Buddhist temple added to a Shinto shrine; a Shinto shrine added to the grounds of a Buddhist temple. Noh stages were built on both grounds, reflecting the spiritual practices of both. Evolving from a traveling form, Noh was performed outdoors, on open-air stages until the 20th century. The open sides of the stage could be boarded up while the stage was not in use. Open-air performances characterized Noh, whether for samurai on the eve of battle, for farmers making an offering for a good harvest, or for nobility enjoying the artistic sophistication of Noh. The 30 extant stages on Sado remain a testament to a time when both Shinto and Buddhism influenced Noh, when all members of society attended and enjoyed Noh plays, and when Noh was performed on open air stages. Modern theaters are usually a traditional Noh stage with a roof, inside a larger modern building that also serves as the auditorium.

As a part of Sado’s heritage, Noh is a contemporary practice—not a lost historical one—as a ritual offering for a good harvest. Farmers on Sado continue this tradition. As was the case in times past, many government officials today, and people of standing who live on Sado, can perform at least a few lines of a Noh play, often more, and also study the chant and the movement. The plays on Sado are performed in a more relaxed atmosphere than in other parts of Japan. There is a familiarity, a sense of cultural stewardship, and a sense of ease, with audience members eating boxed lunches during shows. Some shrines even allow photography—within the bounds common sense, courtesy, and respect for the performance.

Sado Island is fortunate to have a local group, the Sado Noh Awareness Club (Jp: Sado no noh wo Shiru Kai) lead by the indefatigable Kondo Toshihiro. They seek ever-new ways to raise awareness of Sado’s rich Noh history. It is a testament to the excellent cultural stewardship of the Japanese that the place of Zeami’s exile remains for the world a bastion of Noh.

In modern times, each summer, “Motorcycle Noh” occurs on the mainland. Over the course of two weeks, Noh performers and fans tour the countryside together on motorcycles, to visit sites of great beauty and historical interest, and Noh stages of particular dignity and age. A Noh play is performed at every site along the way. It is remarkable that a Muromachi-era art form enjoys such popularity in the 21st century. And as such, Sado is one of the main destinations of Motorcyle Noh.

It is moving to see the reverence that Zeami is accorded by the people of Sado, the site of his exile. The whole island is a tribute to his legacy. It is a cultural marvel that 30, from a peak of 200, historical Noh stages remain for visitors to see, where they can experience a Noh play as a much-beloved aspect of local life and culture.

See more

Related features from BDG

Ernest Fenollosa and the Order of the Rising Sun

Dance for a Passing World

Noh Now

Pure Land Buddhism in Noh: The Shuramono Plays of Zeami

Beauty and Sadness: Reflections on a Japanese Noh Play