Photo by Franklin Price Knott, for National Geographic

I like explorers. I admire adventurers. I’m fascinated by those who were the first to accomplish an unprecedented feat. If you were Xuanzang, the seventh century Chinese priest who walked to India to collect Buddhist scriptures, I admire you. If you were Alexandra David-Néel (1868–1969), the French woman who illegally disguised herself as a male monk in 1924, traveling through Tibet in order to learn mystical Buddhism from genuine masters, I admire you.

If you were Walter Evans-Wentz (1878–1965), the American anthropologist who produced and popularized a translation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead in 1927 that ignited the imaginations of beatnik intellectuals and the psychedelic hippies who followed, introducing millions and generations to abstruse Buddhism in beautiful English prose, I admire you.

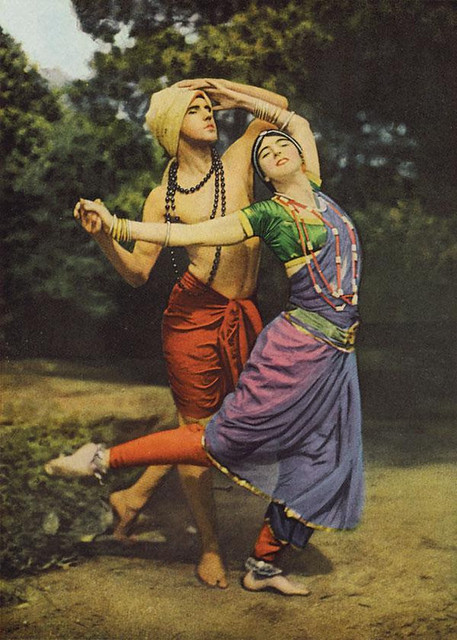

If you were American dance pioneer Ted Shawn (1891–1972), the “Father of American Dance,” who traveled through Asia in 1925 and 1926, performing with Denishawn, the dance company you founded, and documenting the ancient dances you encountered, leaving an unprecedented baseline of Asian dance documentation for posterity, I admire you perhaps most of all.

Adventurous people are easy targets for criticism, both in their own times and with the privilege of hindsight. They are probably eccentric and dissatisfied with normalcy in the first place, brave enough to seek out the new, whether from far away, from different mindsets, or from unknown cultures and ancient masters. No one is more odd than Alexandra David-Néel, but when she describes a monk losing his mind in the wilderness practicing a danced chöd meditation ritual, you believe her.

When contemporary observers assign malignant motivations to early explorers, or project contemptible foibles onto intrepid travelers, I wonder if it is part of a modern sensibility, an incapacity to appreciate other experiences of an originality, a pristine quality that may forever be lost, or now very hard to find? Cynicism rarely sees wholesomeness.

My late mentor, the writer and connoisseur David Kidd, who lived in aristocratic Peking before it fell, and who created a Buddhist art collection for the Shah of Iran, wrote an article for The Atlantic magazine toward the end of his life about a conference that the Shah’s son, Prince Pavlavi-Nia, held in the Seychelles, to which he invited Kidd and Buckminster Fuller, among other great minds. Kidd was a wit and the picture he painted was surreal, but it was all fact. He called the piece, “How We Saved the World, a Late Report.”

Some months later, the editors of The Atlantic sent back the manuscript with a short letter. “Dear Mr. Kidd, Thank you for the manuscript of your wonderful false memoirs…,” going on to explain that the magazine did not print false memoirs. David laughed when he received that letter, “It seems today’s editors cannot even conceive of the existence of such lives!”

Just as he had grown accustomed to barely anyone appreciating what Imperial China was really like, he added the Seychelles conference to parts of his life that he was unable to share widely. Kidd was a character but he was real, too. The amazing things he did in his life were suited to him. Among other things, David was an expert in Buddhism and Buddhist art. Greatly esteemed, his ashes are in fact buried at Daitoku-ji, a temple in Kyoto—with the remains of his beloved Cadillac.

Shawn was, like the French adept David-Néel and Swedish cartographer Sven Hedin (1865–1952), called to his destiny. They led their lives by higher stars. There was purity, a sincerity, and a high-mindedness that was transcendent in Shawn and others of his ilk. At the same time, it would be a miracle if someone didn’t mess up something when these two American vaudevillians met Confucian literati and Siamese courtiers for the first time.

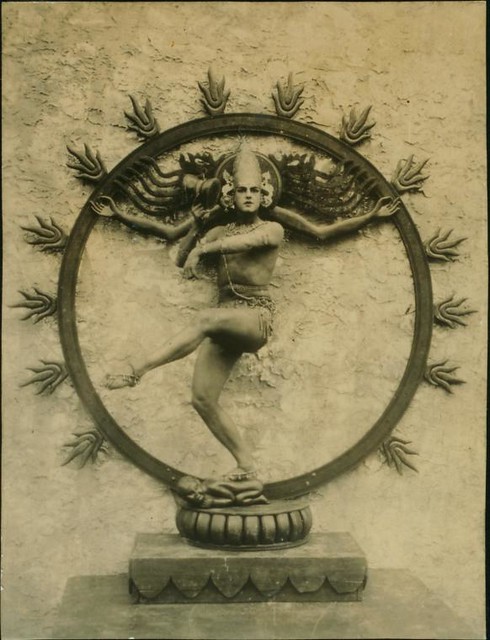

Image courtesy of NYPL Digital Collections

Shawn and his wife, the celebrated dancer Ruth St. Denis (1879–1968), were charming and gregarious and everyone they visited in Asia during 1925 and 1926 wanted them back, as guests and as performers. As foolish as they might have appeared entering villages on the backs of camels, they were performers at heart, and there is no more humble profession.

Everyone knew, too, that the famous St. Denis had the capacity to infuse her dance movements with true mysticism, and that Shawn was a most able, diligent, and respectful student of their arts. They were, quite appropriately, held up as great figures of their time, famous for artistic and idealistic reasons of their own devising.

Whether Imperial China, World War 2, or the AIDS crisis, it is very difficult to imagine and appreciate from a distance the level and quality of charged human interaction, and what character traits are truly called to the surface. Hedin, scholar-explorer Giuseppe Tucci (1894–1984), and the mystic-scholar Anagarika Govinda (1898–1985), like Shawn, were intuitive geniuses. They opened whole new horizons of understanding, in threshold and liminal areas of society, sexuality, and science; in art, dance, research, and spirituality.

Such types of greatness do not belong to the orthodox but rather to those on The Path of the Sublime Weirdo. If ever there was a Buddhist tradition . . . the eccentric is it. Strange people going from here to there is a concise history of Buddhism.

How can we today understand a time when cultures were more truly unknown to each other, when foreign religions were considered taboo, and despite all these barriers of language and custom, humans met and communicated through dance and spiritual practices, to expand their personal and collective consciousness?

Image courtesy of NYPL Digital Collections

There were no male professional dancers in America when Ted Shawn was young. He was studying to be a Christian minister when, aged 19, he was struck down and paralyzed by diphtheria. Many died. Ted took dance classes to strengthen his legs. It changed the course of cultural life in the world of the early 20th century.

From then on he continued life as America’s first professional male dancer, “Father” of American modern dance giants. He invented the profession, outside of ballet, in many ways. Shawn founded the world’s first dance festival, Jacob’s Pillow in Massachusetts, which thrives today and continues to promote Shawn’s embracing ethos toward dance.

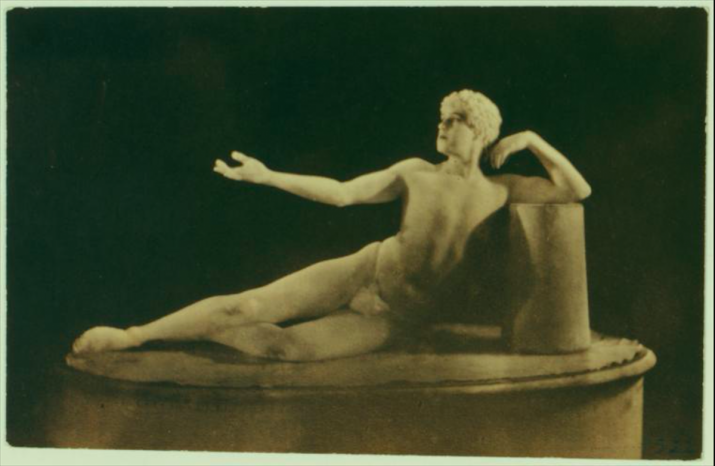

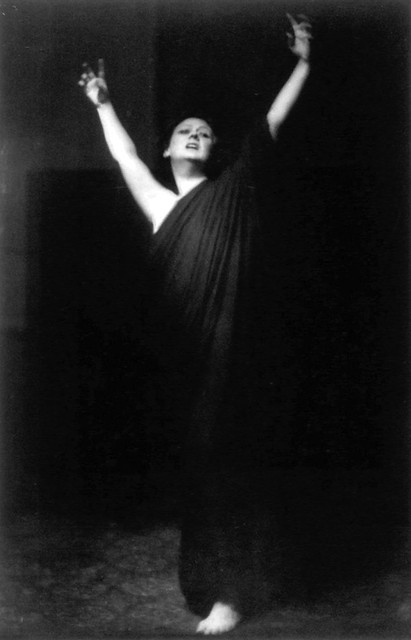

Among inquiring artists at the turn of the last century, there was a general dissatisfaction with stodgy and predictable classical ballet. Isadora Duncan and Loie Fuller put a stop to ballet’s dominance by liberating the female form to itself, becoming its own topic and full expression.

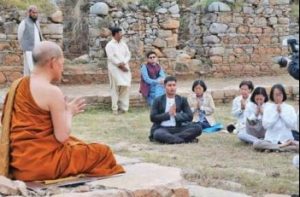

Dance by Arnold Genthe, 1920, International Publishers, Boston

A lifetime of writing and advocacy reveals that Shawn saw better examples of masculinity, spirituality, philosophy, and civic morality in the dances of Native Americans, and in the difficult-to-access dances from other lands, from Japan and India. Shawn filmed Tantric Buddhist monks dancing in 1926. Philosophies of dance attracted Shawn. He was, in fact, a philosopher of dance. How could the underlying principles be known? Shawn deeply wanted to understand the influence of Buddhism on dance, visiting three Buddhist kingdoms and even a Himalayan monastery.

Anthropology was nascent; dance suffered from the scholarly biases of the West. The art of the major civilizations of the world had not yet been widely circulated, and religion, even less so. Egypt was still a craze; a newsreel away. Shawn saw, above all, dance was a transmitted form, like a priesthood, and required its own, living, research methods. It made sense to Shawn that the pre-language of dance was connecting around the world.

Shawn saw through the conventions of Western society, mastered them, and became a scholar himself. His tour through Asia in 1925 and 1926 occurred when the kingdoms of Asia were largely intact. It was the era of Siam, Ceylon, Formosa, Imperial China, and Imperial Japan. Buddhist monks roamed the Himalaya. Much dance was royally supported, and royally intended, performed by dedicated court dancers, mystics, sorcerers, and oracles; martial masters, priests, and ritual adepts. This was like nothing they had ever encountered.

Shawn and St. Denis were guests of royalty everywhere they went in Asia because they were universal artists and open hearts, and world famous dancers. Ambassadors for creativity, they embodied personal authenticity, with a deep respect for culture. They were wholesome exponents of American individualism.

The Asian societies and dancers with whom they interacted had never experienced the intellectual curiosity and independent creativity of the Denishawn dancers. In return, the Americans had never seen so many respected ancient forms of dance, used for serious purposes unknown in the West. It was a moment in world history, guided in its small part, by the benevolence of dancers.

Royalty was infused with myth and divinity. The sobriety of a Confucian geomantic danced ritual, for example, matched the profundity of any high religious occasion, and perhaps contained an element of natural mysticism connected to the role of dance that was lost to the West. Shawn appreciated this. Shawn experienced more ancient dances than anyone in history. His self-actualization included an immersion in ancient Asian dances when his times called him to it.

Shawn knew firsthand about the actual qualities and powers of ancient Asian dances, and their distinctions. His discoveries in dance are as great as other celebrated original accomplishments: climbing Mount Everest, traversing the ocean, translating the Book of the Dead, studying esoteric Buddhism as a white woman in the 1920s. He tasted the source, riding on his own brilliance. He was an outsized person; larger than life. It is fair to say he worked for Dance.

Whether reaching back in time for first principles, as Isadora Duncan did, or exploring the ancient kingdoms and religions of the world, as Shawn and St. Denis did, the efforts of this creative epoch were not bound by the centuries or the continents. Other forces and priorities of enlightenment were in play.

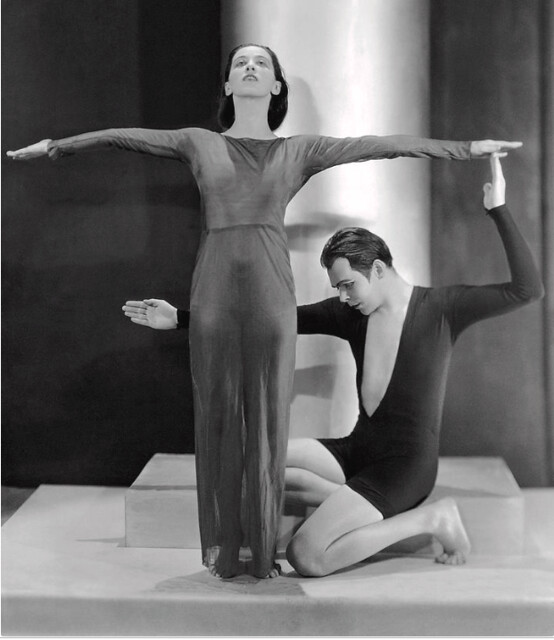

It was a greatness of spirit that caused Duncan to be the most famous woman in the world. The searing pioneers of modern dance—Martha Graham, Charles Weidman, Doris Humphrey, and many others—were students of Shawn and performed with his company The Denishawn Dancers . . .

Photo by Nicolas Muray, 1930, for Vanity Fair

To be a dancer is to have a way of life that is distinct from the ordinary. It requires a greatness of mind and an originality of first experience, even within oneself. My British colleague Gerard Houghton and I have had the rare experience, on several occasions, to have been the first Western people to visit places and attend ceremonies in remote Bhutan.

These were incredible experiences for all involved and in those instances where dances were performed, they took on a deep significance, opened up for those of us humbly serving the historical encounter. No matter the culture of origin, dancers are insiders to one another, relying on language differently, and the body emphatically. Dancers are not outsiders to one another, never foreigners. Sky Dancers all.

Ted Shawn on Buddhism from Gods Who Dance, 1929, selected quotes:

“It is an ironic fact that there is more actual dance connected with Buddhism itself, than almost any other religion.”

“Buddhism did not destroy or supplant the religion of the people previous to its coming, but it adjusted itself and fitted in with the gods that were already worshipped. Perhaps this explains it? For in Burma, Ceylon, and Tibet, three of the countries for which Buddhism is the official religion of the country and where it is most powerful, I have seen dancing in connection with Buddhist temples and Buddhist religious festivals. This then means that the primitive people of Tibet, of Burma, and of Ceylon, had gods who danced, and that Buddhism slowly absorbed both the gods and the dancing, rejecting neither the one nor the other.”

“Dancing is woven in the whole fabric of Buddhist life and goes farther back than the Buddha himself to the gods whom he was too beneficent to banish.”

On Siam and Cambodia: “The sculptured gods of Angkor Vat have danced divinely for 1,000 years, and the dancing of every man and woman in these countries is consciously patterned after these divine models. There is no question that the constant contemplation of these divinely inspired bas-reliefs and the meditation upon the spiritual principles in them embodied, have produced a quality of movement which could never have been produced by any lesser ideal or motive.”

See more