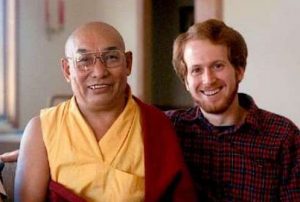

religious studies at Pomona College. Image courtesy of Venerable Zhiru

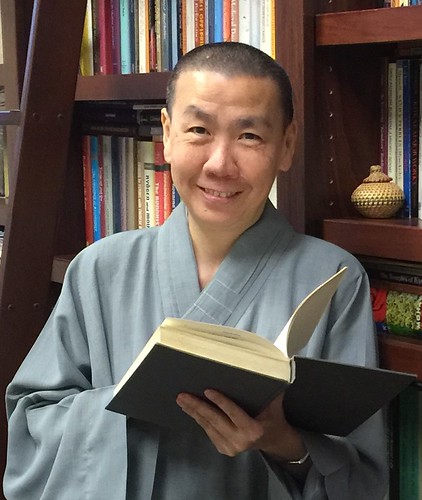

I first became acquainted with Venerable Professor Shi Zhiru (釋智如) in the fall of 2009, when I read her book The Making of a Savior Bodhisattva: Dizang in Medieval China (2007) for a graduate seminar on Chinese Buddhism. From her book, I learned a great deal about Dizang (地藏), a popular bodhisattva in Chinese Mahayana Buddhism. “How cool,” I thought when I learned from the book’s acknowledgement that Ven. Zhiru is a Singaporean Buddhist nun and a professor of religious studies teaching at a prestigious liberal arts college in the United States.

A few months later, when I was back in Singapore for my winter break, one of my former teachers from the National University of Singapore (NUS) told me about a Singaporean nun who was serving as a visiting scholar at the Asia Research Institute (ARI) at NUS. Coincidentally, I found out that the nun my former teacher was referring to was Ven. Zhiru! I quickly made an appointment with Ven. Zhiru and met with her in her office at ARI. We had an enjoyable hour-long chat about Buddhism, academia, and graduate studies in the US. I was deeply impressed by her vast knowledge of Buddhist texts and practices. But even more so, I was happily surprised by her humor, good spirit, and witty comments.

Born in Singapore in 1964, Ven. Zhiru was the youngest of eight siblings. Her father had migrated from Fujian Province in China to Singapore in his early youth, while her mother was a first-generation Singaporean Chinese. Ven. Zhiru’s father ran a small market grocery shop until his business failed. Her mother, a devoted housewife, occasionally took on home jobs such as babysitting and laundry. And when she was born, her older siblings were working and contributing to the family income. Ven. Zhiru’s family was in a better financial situation as she was growing up, and she did not have to help out with the family business while studying. “My older siblings often teased me about being the one born with the silver spoon,” she said with a grin.

Ven. Zhiru began her serious exploration of Buddhism as she was completing her A-levels. At that time, her maternal grandmother fell ill and passed away. Ven. Zhiru’s grandmother was a pious Buddhist, and a long-term vegetarian who had spent much of the second half of her life at the Singapore Buddhist Lodge (新加坡佛教居士林), a lay Buddhist society. When she passed away, her maternal relatives sponsored Buddhist mortuary rites on her behalf. “Much of the ritual language was lost to me, but one phrase, ‘The lotus will be your parents,’ particularly captivated me,” Ven. Zhiru told me. “Later on, I would learn that this was part of the rebirth imagery from the Pure Land Buddhist teachings.” At that moment, this phrase struck a chord with an inner contradiction Ven. Zhiru experienced growing up. Raised in a traditional Chinese family, Ven. Zhiru wondered if she could live up to the prescribed cultural virtue of filial piety. “I seriously wondered if I was capable of the same depth of affection and gratitude that parents feel for their children,” she said.

Curious about the lotus imagery and its implications for understanding parental gratitude, Ven. Zhiru decided to explore Buddhism as another window to her ethnic and cultural roots. Following in the footsteps of her mother, she and a few of her older siblings began to attend Buddhist ritual services at the Singapore Buddhist Lodge. “We loved the chanting and the veneration of Guanyin (觀音), but we soon felt the need to further understand Buddhist teachings,” she said. A short search led Ven. Zhiru and her siblings to Master Houzhong (厚宗), the abbot of Mahaprajna Buddhist Society (慧嚴佛學會), who would later become her ordination teacher. “I remember the first of his Dharma talks I attended—it was on the Mahayana doctrine of emptiness. At that time, I was unable to fully understand the profundity of this Buddhist teaching, but nonetheless I felt a deep conviction that some day I would master this teaching both in terms of understanding and practice.”

From then on, Ven. Zhiru and her siblings regularly attended Master Houzhong’s Dharma talks and took courses at the Mahaprajna Buddhist Society. They became very involved in the Buddhist propagation work of the master. At the same time, she was pursuing her BA degree with a double major in English literature and English linguistic at NUS. “In many regards, I spent more time on Dharma studies and Buddhist work than I did on my course work at the university,” she said.

By the time Ven. Zhiru completed her BA (Honors) in English literature in 1987, she had decided to follow the Buddha’s path and become a nun. “I already knew that the study and practice of Buddhism was more important to me than my interest in literature. Buddhism had very much become the meaning of my life, and I wanted to devote all my time to Buddhist practice and study,” Ven. Zhiru told me. Shortly after she graduated from NUS, she took up her robes under Master Houzhong. “There was no sudden overwhelming catalyst to take up my robes; rather, it felt more like a natural and logical decision after almost five years of increasing conviction that this is indeed the path for me.”

After her ordination in Singapore, Ven. Zhiru’s ordination teacher sent her to Taiwan to receive the full monastic precepts and to receive monastic training at the abode of her grand-teacher, the renowned scholar monk Master Yinshun (印順, 1906–2005). Master Yinshun is widely regarded as one of the greatest Buddhist thinkers of the 20th century. A prolific writer and religious scholar, he received a PhD from Taisho University in Japan, and subsequently became the first Buddhist monk to teach at a secular university in Taiwan. Little did Ven. Zhiru know that she would eventually follow in the footsteps of her grand-teacher.

I asked her: “How was your monastic training?”

“In many ways, it was like a boot camp!” she answered with a laugh. “But the time I spent in Taiwan for my monastic training is one of my favorite memories of my life as a Buddhist nun to date.” The full ordination rites, which lasted for an entire month at Linji Monastery in Taipei, were an intense experience that plunged Ven. Zhiru right into the world of monastic mores and daily etiquette, from nitty-gritty details of brushing teeth and proper meal decorum, to the ethical basis for a harmonious communal life. It was such a jam-packed scheduled that she worried about remembering all the rules and regulations during the sessions of precept teachings and ritual instruction.

On one occasion, the hot water supply cut off while Ven. Zhiru was in the midst of a shower on a cold winter day. “But through it all, I felt very alive and filled with joy,” she said. “Ordination is the first step into a mental freedom that is ironically to be experienced in the many regulations and ritual etiquette that one voluntarily takes on in a monastic life.”

After the full ordination ceremony, Ven. Zhiru went for monastic training at Master Yinshun’s retreat abode in Nantou, a mountainous county in central Taiwan. “Master Yinshun prescribed a study program for me where would I systematically read his writings and discuss the assigned readings with him for about an hour each day,” she told me. In preparation for her meeting with this eminent monk, Ven. Zhiru eagerly read Master Yinshun’s autobiography, An Ordinary Life (平凡的一生), before she left for Taiwan.

“Reading his autobiography, I was already deeply struck by how he experienced and interpreted his life events through the Buddhist teachings of conditioned dependency and emptiness,” Ven. Zhiru said. “But in person, Master Yinshun’s profound realization of emptiness together with his unassuming character provided me with an inspiring model of the Buddhist intellectual and scholar monk that far exceeded all my expectations.” According to Ven. Zhiru, Master Yinshun, for all his intellectual reformist tendencies, was in some ways a Confucian scholar emanating the quiet dignity of long years of a singular focus on his studies. “This encounter with one of the legendary figures of modern Chinese Buddhist history has contoured my own career as a scholar nun teaching in a liberal arts college in Southern California,” she said.

After completing her monastic training in Taiwan, Ven. Zhiru went to the US to pursue graduate studies. She completed an MA in Sanskrit and Indian Buddhist literature at the University of Michigan, and her PhD in East Asian religious history at the University of Arizona. Her dissertation “The Formation and Development of the Dizang Cult in Medieval China” was completed under the guidance of the professor of Buddhist Studies, Robert Gimello. After receiving her PhD in 2000, she joined the faculty at Pomona College, where she has taught ever since.

“It must be challenging for a monastic to study and to teach in the West,” I remarked.

She laughed. According to her, being a Chinese Buddhist nun, dressed in traditional robes, has its challenges, particularly when it come to cultural preconceptions and misunderstandings. Ven. Zhiru shared some of her more amusing experiences; “At airports, I am repeatedly mistaken for being a man on account of my shaved head and flowing robes,” she said. “Once, an old lady seeing me entering the women’s restroom, got flustered and apologized profusely for having used the men’s toilet!”

“To some extent, all foreign students face inevitable challenges and adjustments in new and sometimes radically different linguistic sociocultural environments,” Ven. Zhiru added. I nodded my head in agreement. Having been an international graduate student in the US myself, I can relate to this. “I was fortunate that my transition into North American society and education was relatively smooth as I was used to studying under expatriate teachers and professors from the West at NUS,” she said. “During both my MA and PhD programs in the US, I was in Asia-centered departments, which meant that there were always a good number of Asian students, and the non-Asian faculty and peers all knew one or two Asian languages.”

Graduate school is not without its challenges and obstacles. To Ven. Zhiru, however, all these little challenges were opportunities for spiritual growth. She shared another interesting anecdote. “Once, a classmate in graduate school noticed that my humble bag was fraying pretty badly,” she said. And the next day, with the best intentions, Ven. Zhiru’s classmate gave her a brand new backpack that she has bought for her 10-year-old son but which he had scorned and refused to carry. It was a very childish backpack in brilliant yellow and black. “I was mortified at the thought of having to carry the childish bag as it didn’t correlate to my image of monastic dignity!” she said with a grin. “Then I realized that my ego was at work here and that I was attached to some image of what a monk or nun should look like. I resolved there and then to carry the backpack daily. You can imagine how ‘heavy’ it weighed the first week, as painfully conscious as I was of it!” But in the weeks thereafter, the weight lightened and without realizing, she was hardly even aware of the bag and carried it for a couple of years.

“Some people think that monastics teaching in a secularized educational institution in North America must enjoy an easy, comfortable life,” Ven. Zhiru said. “Actually, when monastics function in a secular educational setting, they experience several disadvantages that, I think, can be quite transformative.”

Displaced from their natural habitats, monastics no longer enjoy the mental and material support from lay Buddhist communities that help facilitate their monastic lives in Asian societies. They are no longer among people who share the same religious and sociocultural frameworks on which their religious lives are built. Instead, displaced in environments beyond their comfort zones, these monastics constantly have to navigate unfamiliar terrains and are forced to question the constructed realities they assume as part of their religious beliefs.

“Such an environment can be conducive for breaking down the deeply entrenched dualisms that we live in, and which our language and conventional norms enforce,” Ven. Zhiru said. “In some regards, a good part of my spiritual growth took place outside of the Buddhist world. My moments of personal transformation, when I moved beyond mere conceptual understanding to intuitive insight, all happened after I was dislocated from my Buddhist roots and anchor in Asia.”

As I drew my questions to a close, I asked Ven. Zhiru what advice would she give to young people. “Always challenge yourself to go beyond yourself,” she told me. She always encourages her students to make good use of any opportunity to expand themselves intellectually and spiritually. “Not so much to win,” she said. “But to bring out the best within you.”