This is a story of esoteric, mysterious Buddhist forces hiding in plain sight across the fabric of Chinese Mahayana and Vajrayana. It is a tale about connections—of threads of living faith that we can discern in the jumbled mess that is world history. Nearly 800 years before the British Empire defeated the Qing (1644–1911) in the First Opium War and forced the Qing to consider them as political equals, the Great State of White and Lofty (bai gao da guo), mostly known as Western Xia, Xi Xia, or the Tangut empire, accomplished the same, forcing the neo-Confucian Song Dynasty to consider the Tangut Buddhist rulers as a force to be reckoned with. During and after the Song-Tangut wars (1038 and 1044) and up until their destruction at hands of Genghis Khan, the Tanguts of the Western Xia (1038–1277) achieved momentous things that are often overlooked.

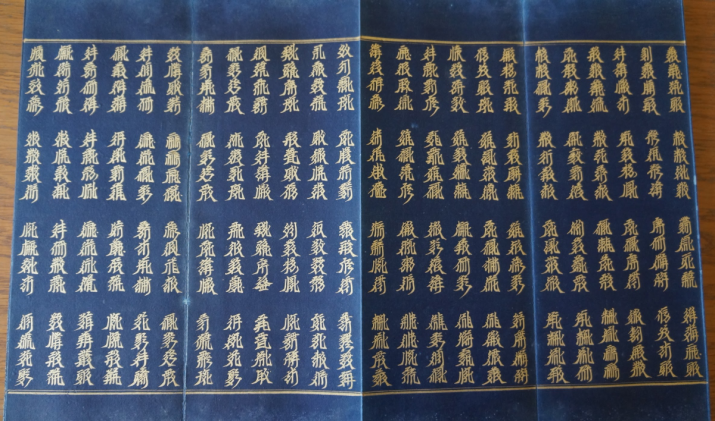

The desert empire of Xi Xia managed to extract concessions from the Song government such as mutual recognition and even financial tribute from the Chinese dynasty. They built an occult script from the ground up, concurrently with empire building, that concealed the esoteric language of Buddhist dharanis, mantras, and mystic revelations.* They reshaped the balance of power across Inner and Central Asia, and through their relations with the Song, Khitans, and Jurchens, contributed to a medieval geopolitical configuration in which all powers balanced each other—from European duchies to nomadic kingdoms. This was, of course, before Temujin’s all-devouring Mongol empire, which despite its incredible achievement in uniting much of Eurasia as a single polity for a short time, consumed many peoples and kingdoms in the process, including Xi Xia.

Scholars certainly cannot expect, without considerable intellectual and financial assistance, to trace specific spiritual lineages to that past. But we can be confident that the spiritual inheritance of the Tanguts lives on in several streams of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism in China.

In the conclusion to her meticulous study on the status of Western Xia’s di shi or imperial preceptors (elite and mostly Tibetan monks who instructed the emperor’s family and senior officials in the Dharma), Tangutologist Ruth W. Dunnell writes: “Our understanding of Tibetan and Tangut Buddhists, their doctrines and associated practices, their resource bases, social networks, relationships with secular authorities (local and state), and the spread and reception of their teaching lineages, is still insufficient. We can, though, put [Western] Xia squarely into the picture of the spread of Vajrayana Buddhism from India and Kashmir, through Tibet to China and the Mongols [my emphasis]. That history of that transmission comes right up to the 20th century.” (Dunnell 2009, 78)

To expand on this contemporary relevance, I would add that it was specifically the Tangut forebears’ ties to the Tibetan Empire (618–842) that brought Kashmiri, Indian, and Tibetan Vajrayana into what is today Inner Mongolia. The world looked quite different a few centuries ago, when the people who would build Western Xia fled from old Tibet, which had been tussling with the Tang (618–907). The Tanguts were in China by the time of the An Lushan Rebellion, and by the time the Late Antiquity’s world order splintered, they were ready to fill in the vacuum left behind by the rapidly retreating Chinese. The near-contemporaneous collapse of the Abbasid Caliphate, the Tibetan empire, the Carolingians, and the Tang dynasty—all unified massive empires—led to an age of slightly smaller but just as formidable medieval dominions, including the Tanguts.

The remote and lonely ruins of Khara-khoto in Inner Mongolia might have been a minor outpost at the edge of the 200-year-old empire, but today it is home to the most recognizable Tangut ruins; a set of wall towers that reach for the skies. It is known among local Mongolians as a city of ghosts and among Chinese as “heishuicheng,” or the sinister-sounding City of Black Water. The haunting ruins hide a complex story of intercultural transmission between the Tanguts and the Chinese. Tangutologist Shi Jinbo notes that the Tanguts absorbed the Han Confucian system of bureaucratic governance, but for its royal family’s spiritual legitimacy, adopted the position of Buddhism within China’s imperial ideological framework. Shi identifies the schools that existed (or at least circulated) in Western Xia as Tiantai, Chan, Pure Land, Huayan, and mizong teachings from both Tibet and China.

In a not-too-old monograph, Shi highlighted several institutional and unique characteristics of Tangut Buddhism: The continuance of architectural and artistic traditions of Buddhist grottoes (particularly at Yulin in Dunhuang), the development of a Tangut Tripitaka separate from the Chinese that endured well into the Ming period, the expansion of Tibetan Buddhism eastwards under the Xi Xia which was a prerequisite for the propagation of Tibetan Buddhism into China proper, the way that the Yuan rulers “absorbed and advocated Tibetan Buddhism as they encountered it on Tangut territory” (Shi 2014, 149), and a relationship of pilgrimage, diplomacy, ordinations, and worship with Mount Wutai beginning with the founding emperors, Le Deming and Li Yuanhao. We know that far from disappearing into the mists of history, the ghosts from the northern Chinese borderland remain very much with us. They apparently favored and patronized the Guifeng Zongmi (780-841) lineage of the Chan-Huayan tradition (perhaps the rulers or scholars of Xi Xia were influenced by Tang-era texts), as well as Maitreya and Manjushri cults.

What is now Inner Mongolia was once a region fit for heroes—horsemen, imperial preceptors, and martial sages. The spirit of this age continues to enchant and educate. We see in Tangut history an eclectic mixture of influential and powerful schools, with several lineages being most prominent, prime among them the Tibetan Buddhist schools that would later be taken up by the Yuan. Those who study these post-Yuan transmissions, including the remnants of the Chan-Huayan tradition, could be said to be studying the inheritance of the Great State of White and Lofty—that kingdom of ghosts and black water.

“I am looking upward—there is only the blue Heaven, I complain to the Heaven—but the Heaven does not respond. I am looking downward—there is only the yellowish-brown Earth. I rely on the Earth—but the Earth does not protect me.” This is the lament of a Tangut poet, who refused to give up resisting the Mongol vanquishers. In the same fragment a cursed epithet for Genghis Khan is given: “the demon-strangler from the underworld.” (International Dunhuang Project)

The most formidable and terrifying conqueror in popular history died on Tangut soil, in 1227, the same year Western Xia was wiped out. It would be left to his grandson to take up the absorption of Buddhism in Asian statesmanship: Kublai Khan, supporter of the Khön house’s Sakya school.

The ghosts sleep. But they never depart.

* See: Secrets of the Esoteric Empire: The Tangut Script (Buddhistdoor Global)

References

Khokhlov, Yury. 2016. “The Xi Xia Legacy in Sino-Tibetan Art of the Yuan Dynasty.” Extracted from: http://asianart.com/articles/xi-xia/ on 20 July 2018.

Dunnell, Ruth W. 2009. “Translating History from Tangut Texts.” Asia Major 3, vol. 22, part 1. 44–78.

McGrath, Michael C. 2008. “Frustrated Empires: The Song-Tangut War of 1038-44.” In Wyatt, Don J. (ed.) Battlefronts Real and Imagined: War, Border, and Identity in the Chinese Middle Period. Palgrave Macmillan.

Shi Jinbo. 2014. “Buddhism and Confucianism in the Tangut State.” Central Asiatic Journal Special Tangut Edition, vol. 57. 139–55.

Solonin, Kirill J. 2008. “The Glimpses of Tangut Buddhism.” Central Asiatic Journal 1, vol. 52. 64-127

Solonin, Kirill J. 2013. “Buddhist Connections between the Liao and Xixia: Preliminary Considerations.” Journal of Song-Yuan Studies vol. 43. 171-219.

See more

Secrets of the Tangut Manuscripts (International Dunhuang Project)

Rediscovery of a Lost Tangut Manuscript (Babelstone)