Almost 1,000 years ago, a beloved keepsake was taken via the Silk Roads before being transported across turbulent tides, until it found itself on a flourishing archipelago. This keepsake would become an object of reverence for some of the archipelago’s inhabitants. It was the Mahapratisara Dharani, a protective text that, according to Prof. Marijke Klokke, professor of South and Southeast Asian art and material culture at Leiden University, functioned as an amulet and serves as the earliest evidence of the worship of a deity called Mahapratisara.

Among the Mahayana pantheon of sambhogakaya (emanation or enjoyment body) buddhas and bodhisattvas, Mahapratisara is not the most well known. Yet she has traveled far and wide, across Eurasia and Southeast Asia, since the 8th century. “I became interested in Mahapratisara when I co-taught a course on Sanskrit inscriptions in Indonesia with Arlo Griffiths. He and his student Thomas Cruijsen were working on a ninth-century copper plate inscription from Central Java that they identified as part of the Mahapratisara Dharani,” says Prof. Klokke.

“The plate also contains the image of a woman carrying a child. They asked me to help identify this depiction. I found it a fascinating subject, specifically because it showed, on the one hand, how Java was very much part of a larger Buddhist world and participated in the pan-Asian circulation of Buddhist texts and images, and, on the other hand, how the text and the goddess seemed to have specific roles in local Javanese contexts. While the three- or four-headed multi-armed goddess Mahapratisara—one of the Pancaraksas or Five Protectresses—has been known from descriptions in Vajrayana texts such as the Sadhanamala, and from Nepalese and Tibetan art, not much was known about her earlier history.”

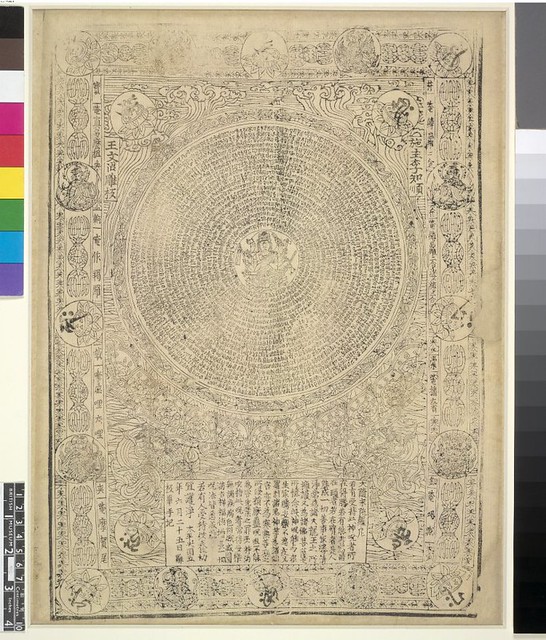

But the academic landscape has changed thanks to recent philological and art historical research. “The origin of the goddess lies in the Mahapratisara Dharani, a protective text that functioned as an amulet. This text circulated in Asia between the eighth and 12th century,” says Prof. Klokke. “The goddess was born when the text became personified and deified, maybe at the end of the eighth century. Her origin explains her name Mahapratisara, which means Great Amulet, which is the name of the protective text, the dharani. At first she was depicted with only one head. Only later, in the context of Vajrayana Buddhist imagery, she developed into a multi-headed goddess.”

© The Trustees of the British Museum. From metmuseum.org

According to Prof. Klokke, the Mahapratisara Dharani and other Buddhist mantras spread along the overland Silk Road and maritime routes of Southeast Asia, with trade hubs in Sumatra, Central Java, and the Philippines. “There are also a number of bronze images depicting the goddess in her one-headed form, all from Java. She is also represented in stone relief at Mendut Temple. She seems to have been important in Java, specifically in the context of successful pregnancy and safe delivery, which is one of the benefits of the amulet, as the text tells us. The inscriptions on the amulet read: ‘The woman who wears this Great Amulet all the time, will have all accomplishments and she will be pregnant with a son every time. Fetuses grow easily, and the expectant woman delivers the baby comfortably.’”

One very clear conclusion from Prof. Klokke’s research is that Indonesia, and specifically Java, was critical as a stronghold for the transmission of Buddhist art and doctrine across Southeast Asia. While the teachings might have spread from India, Central Asia, and then China across to neighboring Asian regions, if one sees transmission as a series of successive “stopovers,” then Java deserves to be as recognized as a region facilitating diverse strands of Buddhist thinking, much like Dunhuang or Kyoto. Prof Klokke quotes Hiram W. Woodward, who stated, in 1980, that: “Java was [. . .] as culturally and intellectually up-to-date a place as any in the world. (Woodward 1980: 19) “It quickly adopted new powerful deities, as it happend elsewhere,” she says.

Mahapratisara is one of the many Mahayana deities whose power can be summoned in a single incantation or dharani. An esoteric counterpart might be the goddess Cundi, who was popular during China’s Tang dynasty (618–907) and remains worshipped in the esoteric Shingon Buddhist School of Japan (Mikkyo). “This type of Buddhism, with its focus on dharanis, seems to have been common in Java, specifically in the eighth to 10th century,” says Prof. Klokke. But Mahapratisara’s popularity did not last and from the mid-ninth century, Shaivism became more influential in Java. “Buddhist culture did continue, as texts and small bronze images from the 10th and 11th centuries suggest. And it found new and powerful Vajrayana expressions in the 13th-century Jago temple in East Java and in temples in Sumatra,” she reflects.

© Museum of Ethnology in Leiden. From courtauld.ac.uk

Prof. Klokke has plenty of work left to do in Java and Indonesia as a whole. “The iconography of Borobudur and Mendut keep intriguing me. There is scholarship that wishes to view them as esoteric Buddhist mandalas, connected to the texts that the Buddhist pilgrims Vajrabodhi (671–741) and Amoghavajra (705–74) carried back to China, but I have been doubting this for a long time,” she said. “I am still not convinced. It does not seem to be in accordance with the art historical record. I feel I have something to contribute there, as an art historian. The first step is getting the dating of the monuments right. At this moment I am working on finishing a book in which I try to establish a chronology of Central Javanese temples on the basis of a stylistic study of the walls’ features, like their ornaments, garlands, monster heads, repeating patterns, and more.”

“After that I would like to revisit Borobudur and Mendut, and work on narrative art. There are still reliefs on Borobudur that have not yet been identified. While Buddhist textual scholarship has been able to develop at a quick pace, art history scholarship is lagging behind.”

Both fields, to be sure, are critical to furthering our understanding of Buddhist history and the divinities that populate it: textual study allows us to understand the doctrinal meaning behind Buddhist art, while the visual content and context might show us how the these doctrines were expressed, adapted, and influenced by a certain community of devotees.

References

Woodward, Hiram W. 1980. “Indonesian textile patterns from a historical point of view.” Mattiebelle Gittinger (ed.). Indonesian textiles: Irene Emery Roundtable on Museum Textiles 1979 proceedings. Washington DC, 15-35.

See more

Buddhist Protectress Mahapratisara (The Met)

Bodhisattva Mahapratisara with the Text of “Da Sui qiu tuoluoni” (The Met)

Mahapratisara, the Buddhist Protectress (The Met)