In 2003, Core of Culture’s dance research expedition team began a five-year project to survey and document the Buddhist dances of the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan. To do this, we needed to make categories to begin distinguishing dances, defining them, and presenting them to the West. Until that time, Cham, the yogic dance of Vajrayana Buddhism that originated in the 8th century and spans the Trans-Himalaya, Tibet, and beyond, had been named variously by those Westerners who traveled through these areas and by later scholars with anthropological intentions.

The first Western dancer to see Cham and make an account of it, in 1926, was Ted Shawn (1891–1972), from the United States, who also photographed and filmed Cham’s Black Hat, Deity, and Stag dances. I am the second, starting in 1999. (Remarkably, we share a birthday.) Shawn filmed with “dance intention,” in other words, with the aim of capturing the choreography and really seeing the dance.

“Devil Dance,” “Demon Dances,” “Sacred Buddhist Dance,” “monastic dance,” “Lamaist mummery”—these were among the labels given to Cham that sprang from correspondent understandings and motivations. The biggest problem with these names is that they are more a reflection of those doing the naming than of that which was being named.

Core of Culture began by distinguishing monastic dance and lay dance. This distinction dissolved: in places where there is no monastery, farmers who perform many of the duties of monks also do the Cham, and they are very good. Then we distinguished religious dances and secular dances, and decided to focus our work on religious dances and how to categorize them.

One already existing distinction was by type: sacrificial dances, magic dances, Yidam (meditation deity) dances, Dharmapala (Dharma protector) dances, comic dances. There were sword dances, drum dances, processional dances. We learned that these distinctions corresponded to choreographic structure, costuming, meditation practice, and author. My colleague in this work—Englishman Gordon Shackleford, who designed the Bhutan Dance Database—and I had both been trained for years in the martial and performing arts while living in Kyoto, Japan. We knew and worked under a different sense of how to touch the living stream of a movement tradition, prioritizing:

1. Its philosophical foundation

2. How it developed as a martial or performing art

3. How instruction was passed from generation to generation

The philosophy underlying Cham concerns its use in Vajrayana practice. For observers, Cham is a kind of rehearsal for the Bardo, or death process, as described in the Tibetan Book of the Dead or the Six Yogas of Naropa. For a monk dancer, Cham is a practice undertaken after the stabilization of the Yidam deity as a visualization in the meditator’s mind, when the monk extends his consciousness to embody the deity and move a tantric form larger than his own body by dancing. It is realization practice: built up and later discarded, like a sand mandala dumped into a river.

The choreographic and technical development of Cham is murky, but not without clues. Clearly it incorporates pre-Buddhist tantric elements appropriated by Padmasambhava (who brought Buddhism from India to Tibet in the 8th century), like mudra (hand gestures) and phurba (ritual daggers). The mental foundation is based in and grows from seated meditation practice. Cham also has elements of functional martial arts, and some Cham conceals a martial form.

Compared to Indian and Chinese dance, Cham is unique. Asian dance generally is rooted, like a martial artist in a stance or the pose of a classical Indian dancer. Cham is gyroscopic, unrooted, wild, and has the rare characteristic of multiple spinning turns to both the left and right. There is a tantric mental technique in Cham as complex as the movement of the body.

Over the centuries new Cham were added, inspired by three main purposes: to add significance to important events, such as enthroning a new head lama; to represent particular metaphysical functions, such as manifesting the deity or conducting a symbolic sacrifice; and to transform into actual dances the revelations of dances by yogic masters. These kinds of dances derive from visions and are called “Ter Cham.”

Drukpa Kagyu school, Tsechu Ging Cham, at the Thimphu Tsechu festival,

Tashichho Dzong. Photo by Karin Altmann, September 2006

A ter is a “treasure,” a teaching or spiritual gift of some kind left by Padmasambhava or his consort, Yeshe Tsogyal, in the 8th century and intended to be discovered by a future saint. Some are actual objects found in physical sites, such as in a rocky crevice, while the teachings, such as choreography, can arise and are discovered in the psychic and mental fields of the enlightened mind. In more than one instance, the choreographer-saint’s vision was of Padmasambhava conducting them to Zangdok Palri, his Copper-colored Paradise, which is filled with dancing supramundane beings called Ging. The Ging would teach a dance to the yogi, and this would become a Cham.

Considering the transmission of the Cham and all its integrated meditation and tantric teaching, we had to seek the source in each case, which in fact proved easily found. Great saints and spiritual leaders who established lineages of Buddhist practice included canons of dance choreographed by them, meant to equal and last as long as the teachings through which the Cham came into being. Where monastic practice was strong, as with the royal Drukpa Kagyu monks, so was the Cham. Where practice was weak, as with the tantras of Dorje Lingpa (1346–1405; one of the Five Tertön Kings, considered emanations of King Trisong Detsen [r. 755–97/804]), so, too, the Cham is more fragile.

Thus, Core of Culture brought forward the first taxonomies of Buddhist dance, for Bhutanese Cham, based on the lineage traditions of the masters who created the dances. The dance lineages of Bhutan are:

1. Drukpa Kagyu School (established in Bhutan in 1222). These Cham are ritual dances of royal monastic style, older than 1616, when they were imported into Bhutan by Zhadrung Ngawang Namgyal (1594–1651) and adapted when he became its absolute ruler.

2. Pema Lingpa (1450–1521). This canon of Cham dances are mystically revealed “Ter Cham,” and include the three-part Ging Sum. New dances, new costumes, and masks have been revealed.

3. Dorje Lingpa (1346–1405). Among the oldest extant Cham in Bhutan, the choreography includes pre-Buddhist archaic forms in the structure, such as advancing lines of dancers, which is not a mandala pattern.

4. Namkha Samdrup (15th century contemporary of Pema Lingpa). This lineage is very rare, performed at only one location, Nangbi, and preserves ancient militia-training dances that were incorporated into the lineage dance tradition.

5. Karma Kagyu School (established in Bhutan in 1470). Also very rare, performed only at Thangbi, and characterized by remarkable backward exits of the deities, as if the mandala were rewinding.

6. Lhodrak Karchu Monastery (established 1672; established in Bhutan in 1962). The Cham lineage of Namkhai Nyingpo, reincarnated. This is the school’s Cham of the 100 Wrathful and Peaceful Deities, in exile from Tibet.

7. Sakya School. Seven dances of the Sakya school remain, although the school has lapsed in Bhutan. Drikung Kagyu monks have made records of these and continue performing the dances.

Image courtesy Karin Altmann

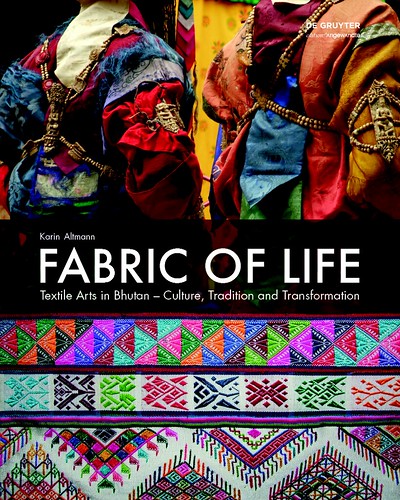

Happily, the taxonomy we brought forward is gaining currency and enhancing the work of scholars and museums. Austrian researcher Karin Altmann has published a stunning, 435-page book, Fabric of Life: Textile Arts in Bhutan – Culture, Tradition and Transformation (De Gruyter, Vienna, 2015). More than a third of the book concerns itself with the specific dance lineages and costumes, explaining their ritual use in Cham. As a result, Altmann has produced one of the best books available on dance in the Himalaya, and in Buddhism. The reader benefits from double specialist lenses: dance and fabric. The mutual illumination is a gift to in-depth cultural understanding.

In Santa Fe, New Mexico, at the Museum of International Folk Art, curator Felicia Katz-Harris has also opened a year-long exhibition, Sacred Realm: Blessings and Good Fortune Across Asia. The media experience for the exhibition makes use of iPads playing the Core of Culture DVD “Cham Lineages of Bhutan,” displaying documentation of the lineages listed above.

These two examples are innovative approaches to ancient topics. The power of the Buddhist lineage sustains the energy and practice of the originator, whose metaphysical experiences define the religious practice of an order. Cham is rooted in the truth of that order’s generative impulse.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global