There is a curious but perhaps not so well known Mongolian legend about a blue elephant who contributed to the construction of a huge Buddhist stupa in ancient India. The elephant labored all his life to build the monument, working to exhaustion. However, his efforts remained ignored, and even the high lama who came to consecrate the stupa forgot to thank him. The elephant became deeply angry and vowed to destroy Buddhism three times in his subsequent rebirths. An earlier mention of the angry elephant is found in a 16th century Tibetan guidebook to the famous Boudhanath stupa in the Kathmandu Valley. Titled History of the Great Stupa Jarung Khasor, Liberation Upon Hearing, it is recognized as a treasure (Wylie: gter ma)—a secret Buddhist teaching that is said to have been hidden away by great masters of the past in order to be recovered at an appropriate time in the future. The guidebook was later translated into Mongolian and circulated in manuscript and printed forms. The Mongol peoples also learned the story orally.

According to the oral Buryat version of the legend, the third and the last rebirth of the angry elephant was Joseph Stalin. It is well known that the Buddhist establishments of the Buryat and Kalmyk peoples (two indigenous groups of Mongolian descent living in Russia and historically adhering to Buddhism) suffered tremendous losses during the Stalinist purges in the 1930s. Monks were forced to disrobe, with many sent to corrective labor camps. Standard charges for Buddhist monastics at the time included “counter-revolutionary activities,” “espionage,” and “organizing campaigns against collective farms,” all falling within the notorious Article 58 of the Soviet Criminal Code.

The situation in Kalmykia had an even more tragic outcome. Not only did all Kalmyk Buddhist monasteries and temples—which numbered around 100 before the anti-religious campaigns—cease functioning by World War II, the entire Kalmyk population was exiled to different areas of Siberia and Central Asia, having been accused of collaborating with Nazi Germany. The Kalmyks were among the 13 so-called “punished nationalities” who were deported to remote territories of the USSR from 1937–57.

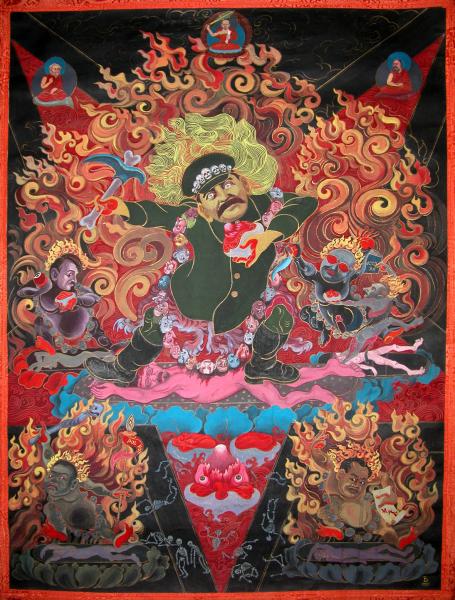

Image courtesy of the author

Surprisingly, I have not heard the about the legend of the blue elephant and Stalin in Kalmykia. Yet I shall feature several visual representations of a similar recourse to Buddhist paradigmatic concepts and images in an attempt to re-interpret and re-problematize recent history. Works of two contemporary artists seem notable in this regard. Both grew up in Kalmykia and received their professional training in southern Russia. While both artists resort to means and structures of Tibetan Buddhist iconography, their paintings are not consecrated objects of religious veneration, but works of secular figurative art.

Red Iconography by Evgenii Bainkharaev was painted in 1990, during the turbulent period of perestroika, and less than a year before the official disintegration of the Soviet Union. Now an established Kalmyk sculptor and painter living in Moscow, Evgenii was then still a student in the Faculty of Fine Arts of the State University in Krasnodar. The structure of this painting is that of a thangka, a traditional Tibetan Buddhist depiction on fabric. The central figure is none other than Stalin, depicted here as a wrathful Buddhist deity. A notable feature of Vajrayana iconography, wrathful deities are enlightened beings who assume a terrifying form to assist others on the path toward enlightenment. Although Stalin is portrayed with a human body, and his face, with its thick mustache, is easily recognizable, he exhibits iconographic attributes typical of a fierce Tantric deity: a crown of human skulls, a necklace of severed heads, a curved flaying knife, a skull-cup filled with blood and human organs, and so on. Following the Indic tradition of depicting terrifying gods and goddesses, Stalin is also dancing on a body. Here, it is the naked body of Leon Trotsky (1879–1940), the Soviet revolutionary and commander of the Red Army who was expelled from the Soviet Union by Stalin in 1929.

Buddhist deities are often portrayed in traditional iconography with an entourage of subordinate figures that represent ministers and attendants of the central character. Stalin’s retinue in this case includes Adolf Hitler, Lavrentiy Beriia, Mikhail Kalinin, and other historical personalities. Above Stalin, in the position of the root lama, we can see Lenin clad in a monk’s robes and holding a sword and a book—well known attributes of Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom. Clad in maroon robes, Marx and Engels are depicted in the upper corners, with the three figures of the upper section representing the “founding fathers” of communism.

Image courtesy of the author

The artist was at first heavily criticized by the Buddhist community and local art critics for employing Tibetan iconography to portray tyranny and dictatorship in the 20th century. The mass violence, terror, and genocide associated with the historical personalities appear totally incompatible with the concepts of compassion, enlightenment, and loving-kindness embodied in the Buddhist pantheon. Yet this paradoxical combination of the antithetical not only makes a strong impression on the viewer, evoking conflicting feelings, it also conveys hidden split meanings leading to multiple interpretations. Rereadings of the painting continue, paralleling the ongoing revisioning of Russia’s Soviet past. One emerging interpretation (which echoes the Buryat accommodation of the blue elephant legend) is that the Soviet era itself, with its political repressions and anti-Buddhist campaigns, had its special “karmic mission.”

A frequently articulated opinion among Russian Buddhists is that the Soviet state suppression of religion revealed the “true ones”—those who remained committed to Buddhism even when it was persecuted and therefore dangerous to practice. This “pure commitment” is often contrasted with the present-day situation in Russia and Mongolia, where being a religious specialist can also denote a form of entrepreneurship, with some Buddhist temples becoming post-socialist workplaces or even new types of small business.

Painted 20 years after the provocative Red Iconography, a perhaps even more puzzling work by Aleksandr Povaev (b. 1948), titled Mao and Amitayus, depicts the founding father of the People’s Republic of China as an enlightened Buddhist teacher. Seated upon a lotus throne, Mao Zedong is depicted wearing the orange-yellow mantle of a Buddhist monk over his typical uniform (what came to be known as a “Mao suit”). While his right hand seems to be held in the abhaya mudra, a gesture of reassurance and safety, his left hand rests upon a book. A yellow mantle, a book, and sometimes the abhaya mudra can represent iconographic attributes of Tsongkhapa, the Buddhist teacher on whose works the Gelugpa school of Tibetan Buddhism was founded in the 14th century. In this case, however, the image of a book alludes to the “Little Red Book,” or Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong, a collection of aphorisms from the Communist leader. First published in 1964 and designed to fit into the breast pocket of the uniform of the People’s Liberation Army, it was simultaneously a feature of Mao’s personality cult and a must-have accessory to demonstrate one’s loyalty to the regime and to help ensure one’s survival during the Cultural Revolution. The background of the painting consists of 108 identical depictions of Amitayus, or Amitabha, the Buddha of eternal life, traditionally portrayed with a vessel containing the nectar of immortality.

Image courtesy of the author

Povaev has also received his share of criticism from local Buddhists for depicting a persecutor of religion as a Buddhist teacher. During our interview, however, the artist confessed that it was his “art offering to Mao Zedong.” Drawing parallels between Mao and Stalin, he stated that both were “great” historical figures. Depicting Mao together with Amitayus Buddha, the figure traditionally associated with longevity and continuation, the artist underlines the irreversibility of history and the inevitability of the continuation of life. Significantly, he views this painting as his own anticipation and prophecy, able to predict and even influence the future. By showing such a bewildering combination of traditionally distinct artistic elements and styles, incompatible symbols and figures, and historically antagonistic planes of Buddhism and communism, the painter maintains that, in the long run, everything will transform by amalgamating and thereby continue to exist, and that even Tibetan Buddhism and Chinese communism are to co-exist, albeit after evolving into novel forms.

This interpretation (although not ubiquitous in the post-socialist context) reiterates the idiom of regarding political leaders as predestined to accomplish certain actions and being paradoxically integral to the universal Buddhist history. In fact, Mongols living in China have their own version of the blue elephant story, in which it was an angry bull who vowed to destroy the Dharma in his subsequent rebirths, included as Mao Zedong.In addition, the message of the painting, as explained by the artist, appears supportive of amicable post-Soviet Sino-Russian relations in a number of spheres, despite the fact that Russia’s concern to preserve these relations has served as the basis for denying visas for the Dalai Lama, much to the dismay of Russian Buddhists.

The theme of entanglement of diverse religious, political, and cultural dimensions, as well as the narrative of the spiritual revitalization of Russia as “Eurasia,” is integral to post-Soviet figurative art, particularly among non-Slavic groups. Another painting by Povaev, George the Victorious and Tara (2007), is a telling example. Following a well known Christian motif, St. George is portrayed mounted on a white horse, slaying a dragon with a spear. In Russia, St. George is commonly called George the Victorious and is highly venerated as a protector against evil and a patron of the military and agriculture. The principal patron saint of Moscow, his equestrian image is vivid in Russian state heraldry. According to hagiographic legend, St. George killed a dragon that demanded human sacrifices, thereby saving the princess chosen as the next offering for the serpent monster. While the image of the princess is often omitted in Christian iconography, in the center of the Kalmyk painting we see a square thangka of White Tara, the most popular female Buddhist deity venerated among Mongols as a buddha of long life. The goddess is depicted with her immediately recognizable attributes: radiant white skin, seated in a lotus pose, with a five-leafed crown, and, most importantly, sevens eyes, including the eye of foreknowledge on her forehead and eyes on the palms of her hands and the soles of her feet.

Palmov National Museum of Kalmykia. Image courtesy of the author

The artists explains that he wants to show that St. George, being the national protector saint of Russia and an iconic representation of the Russian state, is also guarding White Tara. The Buddhist goddess in this context signifies Kalmykia and the Kalmyk people, historical followers of Buddhism living in Europe and situated within Russia, in both geographical and political terms. “We [the Kalmyks] have been living in Russia for so long.” says the artist. “Everything has become intertwined as we live side by side. George the Victorious defends Russia, but he is also a protective deity of Kalmykia. He protects everybody.”

Yet another significant meaning emerges here, which is again connected with the Buddhist trope of reincarnation. Historically, White Tara is thought by the Mongols—particularly those living in Russia—to have been reincarnated in the line of Russian rulers. Thus the Empress of Russia, Catherine the Great (r. 1762–96) is said to have been recognized by Buryats as an emanation of the goddess for legitimating in 1764 the institution of the Pandito Khambo Lama, the supreme head of Buddhism in Russia. Another popular version, albeit also contested by historians, states that it was the empress Elizabeth (r. 1741–62), who was proclaimed the first Russian reincarnation of White Tara for recognizing Buddhism as one of the legitimate religions of the Russian Empire. Other sources indicate that even earlier Russian monarchs were referred to as White Tara among Mongols.

The identification of Russian tzars, whether male or female, with the Buddhist goddess continued through the 19th century, and was resumed in 2009, when president Dmitry Medvedev was declared a rebirth of White Tara by the leader of Buryat Buddhists. However, it is also popularly believed among Russian Buddhists that every Russian ruler is inevitably an embodiment of White Tara, whether officially recognized or not, as it is the goddess herself who chooses to be continuously reincarnated within Russia’s political leadership.