Although Vesak, or “Waisak” in Indonesian, is celebrated at the national level, the Buddhist community makes up just 1 per cent of the Indonesian population, according to official census data. Moreover, the modern identity of Indonesian Buddhism is still a work in progress. The second-oldest religion in Indonesia, Buddhism was transmitted from India alongside Hinduism. While Borobudur epitomizes the heyday of Mahayana Buddhism in Indonesia, the historical impact of Buddhism is considered limited. Within a five-kilometer radius of Borobudur, more than 30 monuments have been discovered, most, as UNESCO describes, in a “deplorable state.”* Apart from Borobudur, Mendut, and Pawon situated between the two, the rest of the monuments are identified as Hindu in origin. When Islam arrived, Buddhism seems to have faded into oblivion.

It was not until the 17th century that Chinese immigrants began to reintroduce Mahayana Buddhism to the islands.** Theravada Buddhism was disseminated after the 1934 visit of Bhikkhu Narada Thera (1898–1983) from Sri Lanka. Various Buddhist organizations, including WALUBI (Representatives of the Indonesian Buddhist Community), were established, dissolved, and reestablished in the subsequent decades. Among the Buddhist masters seeking to re-establish Buddhism in Indonesia was Bhikkhu Ashin Jinarakkhita (1923–2002), who revived Buddhism by advocating Adi Buddha as the supreme “god” in response to Pancasila, the mono-theist foundational ideology of the Indonesian state. Born to Chinese parents, Jinarakkhita was ordained by both a Chan master from China and a Theravada master from Myanmar.

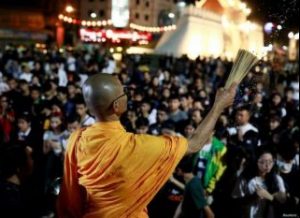

As pointed out by Leo Surydinata, a leading historian with an interest in ethnic Chinese communities in Southeast Asia, both Jinarakkhita and Hartati tried to Indonesianize Chinese Buddhism by diminishing the Chinese elements. While this approach was supported by the government, it caused schism within the Buddhist community.*** Indeed, the majority of Buddhists in Indonesia are of Chinese descent, but at the Waisak ceremony this year more Theravada monks were present. Moreover, all attendees were presented with a book as a gift, which was written by Ajahn Chah (1918–92)—one of the most influential Theravada masters of our time.

On a personal level, I felt as if my identity was constantly shifting throughout the day between that of a tourist, an art historian, and a pilgrim. Like my fellow travelers, I came to Borobudur to appreciate her antiquity and grandeur in person. I certainly related less to WALUBI, who practice Buddhism in a different religious and socio-political context. However, as someone who has worked with various Buddhist communities for years, I wanted to enact the religious experience in the presence of the Three Jewels—the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. Following other devotees, I ascended the nine platforms of Borobudur and circumambulated the top platform clockwise three times.

Meanwhile, my academic mind kept questioning how much of what we think we know about Borobudur is true. For instance, while the procession visits the three Buddhist sites of Mendut, Pawon, and Borobudur, there is no evidence of any historical connection between the three sites. In addition, scholars argue that Borobudur was constructed to reflect Buddhist cosmology of kamadhatu (the Realm of Desires), rupadhatu (the Realm of Forms), and arupadhatu (the Realm of Formlessness), but the themes of the reliefs and numbers of vertical levels do not match extant textual descriptions of the three realms. Was this symbolism in the mind of the designer? What kind of rituals were performed at Borobudur? Historical records and contemporary artifacts are so scarce, we can only attempt to make sense of the fragmented and disorderly information accessible to us today.

For most of that day, however, I was nobody. I waited in uncertainty and darkness for the final moment when we would release the sky lanterns, as that was how the night was supposed to culminate. At midnight, we all sat on a grassy clearing to the west of Borobudur, each with a lamp lit up on the side. We were guided to meditate together, and the sangha recited mantras and gave blessings. I could have fully engaged in a Buddhist manner, or tried to think how sky lanterns were invented in China, or considered their environmental impact. Instead, I fell asleep; simply choosing to lie on the grass. After being awake for more than 18 hours on this tour of Borobudur, my excitement had waned, turning into contentment and a sense of security.

At one point, I woke with a start, to find that people had just started distributing lanterns. Releasing sky lanterns is teamwork requiring 3–4 people and we were lucky to launch four lanterns altogether. Some of us wrote wishes on a sticker handed out by our guide and attached it to a lantern before setting it off. I did not write anything; in fact, I forgot that sky lanterns are used to make wishes. Gazing into the sky, into the sea of floating lanterns near and far, and to the full moon, I breathed in the wonderful energy around me—the joy, the hope, the sense of paradise. I felt that my dream had already come true. I felt all dreams were true. There was no dividing line between dream and reality. There was no dividing line between you and me. We were one and we are one.

* Restoration of Borobudur (UNESCO)

** The process was similar to that in Malaysia. See: Migrating Beliefs: Chinese Buddhism in Penang (Buddhistdoor Global)

*** Suryadinata, Leo. 2005. “Buddhism and Confucianism in Indonesia”, in Chinese Indonesians: Remembering, Distorting, Forgetting. Edited by Tim Lindsey and Helen Pausacked. Clayton: Monash Asia Institute.