Seoul—a city of ten million people, dazzling skyscrapers, and high fashion. Driving along Apgujeong Rodeo Street, the storefronts of Dior, Gucci, and Louis Vuitton flash by. This is the heart of Gangnam, the South Korean capital’s flashiest district. Gangnam rose to fame in 2012 when the eponymous “Gangnam Style,” a song by pop star Psy, topped international charts and the accompanying video, a revelry of consumerism, broke records on YouTube.

In the midst of the glitz and glamor, however, right opposite a gigantic shopping mall, stands an ancient center of spirituality and tranquillity. Seoul’s Bongeunsa temple dates to the 8th century, a time when Gangnam consisted solely of lush green rice paddies.

Today, the shiny skyscrapers provide a sharp contrast to the traditional dancheong or bright coloring that characterizes the wooden temple architecture. The temple’s surroundings testify to Seoul’s incredible growth in recent decades, but also epitomize Buddhism’s struggle to remain relevant in contemporary Korea.

Buddhism reached the Korean peninsula in the 4th century, and flourished. Over the centuries, the meditation-based Buddhist practice known as Seon, a cousin of Japanese Zen, grew dominant. Korean Seon stresses asceticism, monasticism, and meditation. How relevant is this form of Buddhism in Seoul today? And how does Bongeunsa’s monastic community relate to Gangnam and its jet-setting denizens?

Buddhism’s history as Korea’s main religion stopped short in the 14th century. During the reign of the Joseon dynasty, from 1392 to 1897, the royal court suppressed Buddhism in favor of a neo-Confucian ideology. Buddhist monks and nuns were ostracized from society, forbidden to enter the cities, and banished to the mountains. Although the worst of the restrictions were lifted at the end of the 16th century, when the war effort of Buddhist monks proved vital to Korea’s defeat of invading Japan, it was only in the 20th century, at the start of the Japanese colonial period in 1910, that Buddhism was rehabilitated.

Today, almost 23 per cent of the population follows the Buddhist path. The Seon Jogye order is the most popular Buddhist order in the country, and Bongeunsa is its second most important temple. The order’s president, Venerable Jaseung, oversees the management of almost 2,500 temples, and is spiritual guide to millions of South Koreans. Yet some fear for the future of Buddhism in the country, arguing that demographics spell the decline of the religion: Korea is an ageing society, and most practicing Buddhists are elderly. Others fear the onslaught of Christian fundamentalism, pointing to the recent vandalism of Buddhist images and temples, and the disproportionate number of Christians in positions of power in both politics and business.

Notwithstanding such concerns, when I visit, Bongeunsa is a hive of activity. The temple’s car park is filled with luxury cars. Elegantly dressed visitors, men in pin-striped suits, ladies clutching their purses, bow to the guardians of the four directions as they pass through the Gate of Suchness—the Jinyeo-mun—which serves as a reminder to see things as they are, beyond our own projections. They then make their way up to the temple proper, occasionally stopping and bowing once more before the stupas containing sharira, the crystal relics found among the ashes of the temple’s cremated masters.

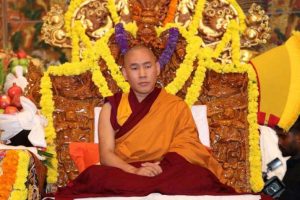

In the Pavilion of the Dharma King, men and women sit in silent meditation. Three thousand three hundred miniature statues of Gwanseum Bosal, the bodhisattva of compassion, grace the walls. Hundreds of dazzling lanterns are suspended from the ceiling, their fuchsia hues a feast for the eyes. My guide, a lay volunteer, tells me she performed 3,300 prostrations in front of Gwanseum Bosal before her daughter sat the university entrance exam. She is chirpy, and honest about the challenges she faces on the Buddhist path. She tells me she struggles to let go of the expectations she has of others, and especially of her children.

During the Joseon period, Bongeunsa persevered in the face of the dynasty’s oppression of Buddhism. This spirit of endurance pervades the mentality of the temple administration today. In recent years, the temple has worked tirelessly to establish itself as the center of Korean Buddhist practice in Seoul. Its approach is thoroughly modern: social and outreach projects are organized to promote Buddhism among the community, lay people are invited to be part of the everyday running of the temple and take foreigners around like myself, and all financial records are part of the public record.

At the heart of these efforts is the need the temple fulfills within the Gangnam community. After my tour, I enjoy traditional Korean green tea with Won Keong, a resident nun of Bongeunsa. Shaven-headed and dressed in the light gray robes typical of the Seon school, she laughs, giggles, and smiles. She talks about Gangnam and the thirst for money and power—a thirst, she says, that is a form of attachment, one of the three Root Poisons in Buddhist philosophy. Those that suffer from it come to the temple to purify themselves. The sword of Dhrtarsastra, the guardian of the East, slashes through their defilement.

I walk to the edge of the temple complex, where a giant statue of Gwanseum Bosal stands some 75 feet tall, overlooking Gangnam. He hears, sees, and feels the cries of the world’s suffering beings. In his hands he holds a bottle of nectar, to quench the thirst for truth and peace.

The people of Gangnam come to Bongeunsa to find balance in their lives and to replenish the mind. Their growing numbers are reflected all over Korea, where each year more and more high-flying businessmen and -women sample the Buddhist retreats on offer at Buddhist temples, dotted across the southern peninsula.

In the midst of the urban rat race, Bongeunsa is a haven of compassion where visitors, stepping through the Gate of Suchness, can shed society’s expectations and be seen for who they are. Instead of modernity pushing history out, in Korea it embraces it ever more tightly, an intimate and vital coupling that restores equilibrium in our hectic modern age.