Meditation is like dancing inasmuch as the experience is entirely individual. The body becomes the laboratory for energetic exercises, and the embodiment of prescribed shapes. Both meditation and dance induce transcendent states beyond mundane perception. Amazing things occur in the mind-body complex that go beyond both, and speak universally.

Dancers, musicians, and bodhisattvas in the mural paintings of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves from the Northern Liang (397–439) and Northern Wei (386–584) dynasties are some of the most expressive figures in all the caves in the Dunhuang area—expressionistic even, sharing the qualities of being personal, highly subjective, and spontaneous. What stands out among these extraordinary and powerful paintings is that they communicate Buddhist principles of being beyond the self, even as the individual is celebrated. Self-expression of the no-self.

Dancing and meditating seem consummate personal acts. They are as individual and non-linear as dreaming. Dancing and meditating are acts through which the self is transcended in the course of artistic and mental expression. I was taught, “There is no difference between [the Universal] Mind and [the individual] mind.” What is the Universal Dance? How does the whole universe dance when the dancer does? Call it Buddha Mind, call it Buddha Dance. Or mind, or dance.

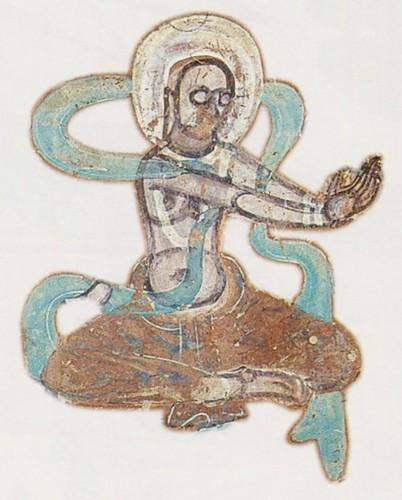

Northern Liang dynasty (397–439), mural painting.

After The Complete Collection of Dunhuang

Grottoes, Vol. 17, Paintings of Dance, The

Commercial Press, Hong Kong, 2001, p. 21

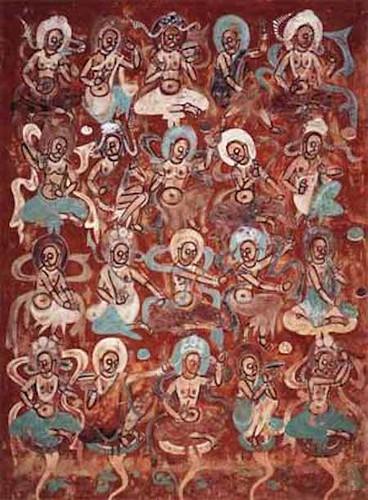

In Cave 272 at the Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes, which dates to the Northern Liang dynasty, 36 bodhisattvas, seated in meditation on lotus blossoms rising on long stems from the mud of a lotus pond, perform emphatic yogic gestures signifying spiritual practice, play music, and listen to the Buddha. The idiosyncratic behavior of these bodhisattvas calls to mind the anti-establishment eccentricities of the 84 Mahasiddhas, or, realized yogis who became symbols and exemplars of tantric practice. All of these characters are meant to depict humans and what they can attain: personal enlightenment, universal compassion, and a cosmic dimension. The percussive images in Cave 272 soar through time and consciousness, a lofty language in itself.

Mogao Cave 272, Dunhuang. Northern Liang dynasty

(397–439), mural painting. After The Complete Collection of

Dunhuang Grottoes, Vol. 17, Paintings of Dance, The

Commercial Press, Hong Kong, 2001, p. 20

These lotus-borne devotees are performing a prescribed series of movements. They are broader than mudra, or energized hand positions. It is a kind of yoga, a spiritual technique, done while seated in meditation. Dancers play music and musicians dance. Other gestures look like the hermit-calisthenics called, in Tibetan, Trul Khor. The body is completely engaged, and so, too, the mind. Body and mind are one. Otherworldly music. Beyond words, beyond self, a wholeness. The mural as a whole—two panels on either side of a sculpted Buddha—emanates the electrifying effect the Buddha’s teachings have on the attuned consciousness. Blossoms open.

The anonymous painter has taken this historical scene—the Buddha surrounded by disciples—and gone beyond to depict a spiritual condition: an array of bodhisattvas, an order of movement symbols communicating a supra-rational, direct, entirely individual experience of transcendence. The painter has revealed the highly charged atmosphere possible when transported by the Universal Mind. Conscious Potential before and beyond ego creates the artistry of the disciples’ union with the Buddha, as well as the power of the painter’s own bold line.

Like the seated Buddha at the top of the mural, these sages are what they look like: the inner state is manifest in the outer form of practice. It is a state of grace. This is the first unity that leads to ever-greater comprehension of unity: a foundation for meditation, for dance, for clarity and insight. It is the materia prima of gnostic experience, in dance, meditation, or the practice of art.

Monastery, Ladakh, winter 2012. Photo by Nathan Whitmont. From

Core of Culture

The language of words and the language of symbols are two different mediums of expression and conscious awareness. Intellectual activity relies on words and reason. The symbols of the creative imagination are multi-dimensional, like a mandala, expressing deeper levels of consciousness.

Breath is an element of embracing nature we can control: we can associate it with our thoughts, attune it to our state of mind, use it to direct energy and inspire the physical body. Dancers and martial artists make breathing part of their art and their conscious state of being—which is their art, one of refined intuitions. Meditation takes breathing from a physical instinct to a method of mental cultivation. Body, mind, and breath unite in direct experience. Now add movement and meditation, at one with a new flow.

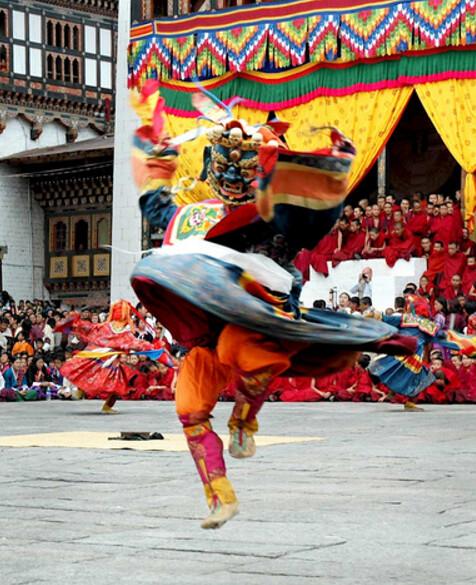

This is a liberated mind, free to express artistically, to use visualizations for meditation and dance. This is the cosmic body. In Bhutan, there is an oral teaching regarding deity visualization meditation for monks performing Cham dance: “Swim along with the deity.” The visual understanding is that the deity is essentially the same shape as the masked dancer, but larger in every way: the dancer and deity overlapped, interpenetrated, as it were. It is easy to understand why the best Cham dancers are also those highly skilled in meditation.

In Buddhism, clarity of thought is incomplete without clarity of vision. The precision, spectacle, and mastery associated with a painted mandala take physical form in Cham dance—the two forms, dance and painting, unite in a visualized mandala both share. They are activations of meditation. Cham is a mandala played out in time. The self as ego is not an actor at these levels of personal consciousness of the universal. The individual is never more fully present than when a dancer dances or a practitioner meditates. This coupling of mind and body in visualization is essential tantric practice.

Thimphu Tshechu festival, Bhutan, 2005. From Core of Culture

Unification of body and mind generates the magnificent deities in painting and sculpture, in Cham dance, and in meditation practice. It has inspired the extraordinary paintings in Dunhuang Mogao Grotto Cave 272, where the subject of transcendent expression is painted with the clarity, insight, and energy of high-minded painters who left no names. They left instead universal artistic expressions of the experience of Buddhism, as individual as the dancers who danced in their paintings and the monks who meditated in the caves.

It is easy to see why artists in every era are drawn to Buddhism, its techniques for functioning at essential levels, and the potential for artistic practice to expand consciousness. A connection to the techniques of ancient gnostic dance is something Western culture has lost. Buddhism has kept it vibrant.

dynasty (397–439), mural painting. After The Complete

Collection of Dunhuang Grottoes, Vol. 17, Paintings of Dance,

The Commercial Press, Hong Kong, 2001, p. 20

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Dance at Dunhuang: Part One

Dance at Dunhuang: Part Two – The Case for the Feitian

Dance at Dunhuang: Part Three – The Sogdian Whirl