Has there ever been a civilization that invented a script, only to deliberately conceal its contents and meaning? This is precisely the mystery of the Tanguts of the Western Xia (1038–1227), who ruled a large desert kingdom in northern China and modern Mongolia. We can meet them through the chronicles compiled in the mid-14th century, the Song shi, Liao shi, and Jin shi. However, it is never helpful to examine a people through the eyes of their enemies alone. We can learn far more from the artifacts they pass on to us, scarce though they may be.

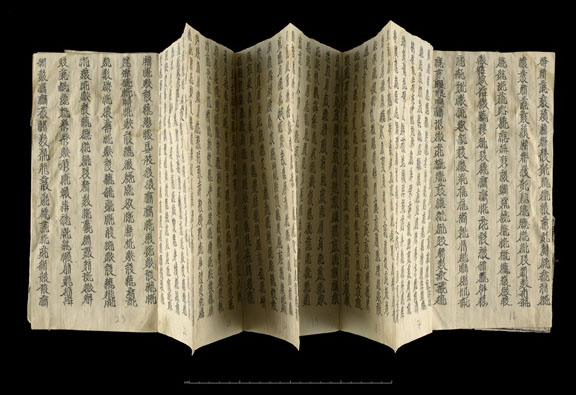

The people of the Western Xia were pious Buddhists and Confucians. They not only left behind beautiful art in the Mogao and Yulin caves, but also a beautiful yet eye-wateringly complex script. The two are interconnected in exploring the secrecy of tantric Buddhism, which was the religion of both the majority populace and the state. Despite the Tanguts’ relative openness to adopting certain aspects of Han Chinese culture (particularly techniques of drawing and painting), the art and doctrines of Buddhism and their singular language remained powerful driving differentiators of Tangut identity from their regional rivals (the Han Chinese-ruled Song empire, the Jin, and the Liao).

The complexity of the Western Xia’s written culture becomes ever more acute when one matches up any given Tangut word with a Chinese character. It is, according to Berthold Laufer, the most complex writing system in the world (Laufer 1916, 4–5). Moreover, just four years after Emperor Li Yuanhao (r. 1038–48) engineered his state and formed the Tangut empire, his scribes and ministers had already invented no less than 6,000 ideograms. There were so many that 3,000 remained unused even in the Tanguts’ native literature or translations of Chinese works (Kepping 1992, 373–4).

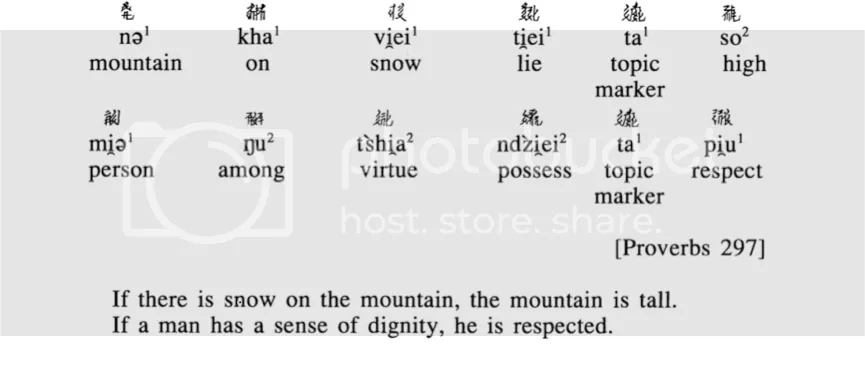

The rationale for implementing such complexity is baffling. A purposely complex language does little for mass literacy and memorization. However, in her research, Ksenia Broiovna Kepping found that the graphic structure of the ideograms exhibited symbolic homophony for those who understood them. In one example, Kepping notes that an enigmatic statement like “If there is snow on the mountain, the mountain is tall” is uttered in the same way as, “If a man has a sense of dignity, he is respected.” This is homophony that goes far beyond single words and is built into images that are connected to a specific proverb (snow as dignity, mountain as man).

Yet, perhaps the greatest power of the Tanguts’ words lay not in their utterance, but in their logography: beneath the words’ superficial meanings were encoded sets of homonyms that invoked sacred locations, deities, mantras, teachings, and hymns. According to Kepping, the entire Tangut script was planned for use in the specific religious contexts of tantric rites. This was a theocracy that was so devoted to its state religion that the basic foundation of its society, and language, was constructed around esoteric meaning. The secret rites performed by the imperial family were central to the functioning of the state.

The Tanguts seized the Mogao caves, along with many Buddhist sites, during their early imperial expansion in 1068. As pious Buddhists, they reinforced the stone of Mogao’s most famous cave and facade, Cave 96. They also added the corridor that visitors still use to gain access to the sanctuary’s giant Buddha, constructed during Wu Zetian’s reign in 695. The Tanguts wished to communicate with and invoke the powers that inspired these gargantuan sculptures. Perhaps they felt that their script, unique in history, was one of the means through which they could achieve this.

I remain convinced that the “State of Ten Thousand Secrets” (referred to as such in a Tangut ritual song) was one of the most remarkable civilizations in Inner Asia and the world. The Tanguts were unsurpassed patrons of esoteric Buddhism, and their writing script is arguably the most complex logographic system humankind has ever devised. The great tragedy is that this ingenuity, which was pioneered by a medieval Buddhist civilization, might never be fully understood despite the hard work of a handful of experts.

References

Kepping, Ksenia Broiovna. 1994. “The Name of the Tangut Empire.” T’oung pao, Second Series 80: 357–76.

Kwanten, Luc. 1994. “The Structure of the Tangut [Hsi Hsia] Characters.” T’oung pao, Second Series 75: 1–42.

Laufer, Berthold. 1916. “The Si-hia language, a Study in Indo-Chinese Philology.” T’oung pao 17 (XX): 1–126.

Discover more

Hill, Nathan, ed. 2012. Medieval Tibeto-Burman Languages IV. Leiden: Brill. —This is a superb volume on some of the more fascinating facets of Tangutology, including a monograph on the Tangut consonant system by Sun Bojun and Chung-pui Tai, and the teachings of Chan master Nanyang Huizhong in Tangut translation.