Image courtesy of the artist and Hirschl & Adler Modern

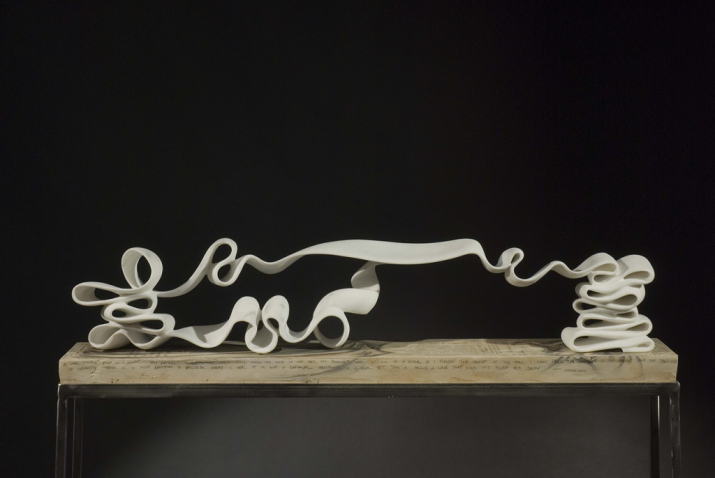

Typically, when we behold a marble sculpture we are impressed by the artist’s ability to transform an amorphous block of stone into a recognizable form—the lovely figure of a dancing Greek goddess or the regal bust of a Roman emperor. The sculptor’s skill with the chisel has traditionally been focused on the creation of perfect proportions, realistic detailing, and a strong sense of presence—so much so that some sculptors have claimed that the form was always present within the stone and that they merely released it. The complex, abstract forms that American sculptor Elizabeth Turk releases from marble are no less skillfully rendered than many traditional sculptures. In works such as Cage: Box 7 (2012), a single strand of marble ribbon appears to twist and tangle to form elaborate cages, collars, or skeletons with a delicacy that seems impossible considering the hardness of the material. With Turk’s work, however, one is struck not so much by what is present but by what is absent.

By carving away so much of the stone (initially with electric grinders and then using small files and dental tools), Turk draws our attention to the empty space in which the winding tendrils of stone appear to float. In the same way that the Japanese Zen Buddhist ink painter gives equal importance to the white space (Japanese: ma) surrounding each black ink brushstroke, Turk highlights the emptiness or nothingness embracing the solid elements of her sculpted forms. Although it lightens the whole sculptural form in physical terms, the empty space challenges us to perceive the stone from a different perspective aesthetically and philosophically, to realize that the absence of stone is as weighty as its presence.

Turk has spent a lot of time studying rocks and their characteristics. She grew up mainly in Southern California, New Mexico, and Colorado, and in each of these regions was drawn to the beauty of the natural landscape. Her father was a geologist who instilled in her a fascination with stone from an early age, although she did not immediately become a sculptor, or even an artist. Instead, she studied international relations at Scripps College in Claremont and then moved to Washington, DC, to work in international relations. While in DC, Turk visited museums and took art courses, and eventually decided to pursue art by enrolling in an MFA program at the Rinehart School of Sculpture, Maryland Institute College of Art.

Turk’s early sculptures were in bronze, but after appearing in an exhibition with Louise Bourgeois, renowned for her giant bronze spiders, she decided to find a new medium for herself. She discovered some marble left over from the Lincoln Memorial and began working it and soon fell in love with the material, enjoying the timeless feeling of working with such an ancient material, as well as the challenges of pushing its technical boundaries. Despite the noise and dust involved with working stone (she must wear ear protectors, safety glasses, and a dust mask), Turk finds the work to be a deeply spiritual process. “Often I have thought that the repetition in sanding marble works has acted as my vehicle for meditation,” she explains. “The repetition in movement is as a doorway to re-order my mental state.” Her work also allows her to engage in metaphysical musings as she manipulates her stone, in particular as she explores the boundaries of paradox: the lightness in weight, the emptiness in mass, the fluidity of the solid, the contemporary in the traditional, extended time expressed in a single moment.

For more than 20 years now, working in both New York City and Southern California, Turk has coaxed this smooth metamorphic rock into breathtaking lyrical forms, earning her a number of major awards, including a MacArthur Fellowship in 2010 and a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship in 2011. For the latter, she had access to the collections and equipment of the Smithsonian Natural History Museum, and her research here led to a 2014 series of photographs that are connected to her sculptures in many ways, as they too explore positive and negative space while delving deep into the material she was exploring—this time seashells. Her X-Ray Mandala series uses X-ray and photography methods to expose the layering of shell structures, which in turn reveal the strength and beauty seen in the sacred geometry of these normally very familiar natural objects. Although the ordinary shapes of the seashells themselves are absent from these images, what is present instead are ethereal geometric forms that suggest the mystical powers of the natural world, like the mandalas that serve as a focus for the visualization practices of many Buddhists and challenge perceptions of reality.

2014; X-Ray, lightbox, 16 x 16 inches and

48 x 48 inches. Image courtesy of the artist

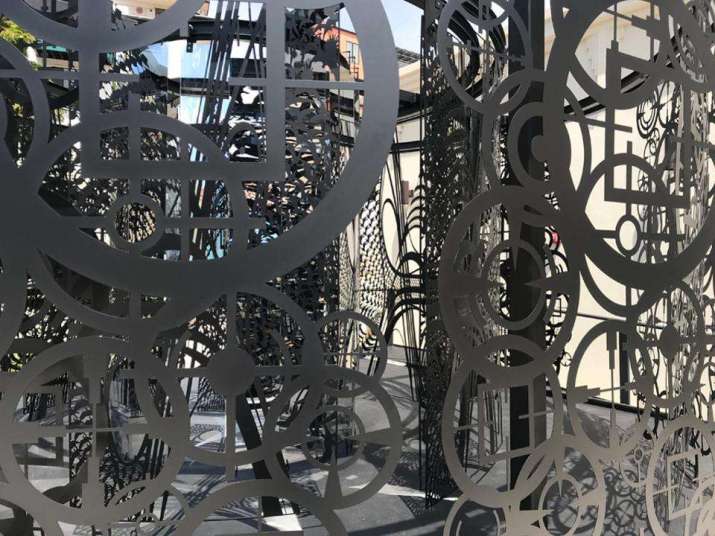

and Scape Gallery

Turk believes that the tenets of Buddhism parallel her spiritual life and her work. “Nature played a profound role in my childhood,” she explains. “Thus all spiritual philosophies where humans live inside the arms of the natural world, not outside of it, resonate strongly with my soul. The spirit of change, which is fundamental in any theme of impermanence, is acutely alive in all my work.” Change and impermanence—and also absence—are the main focuses of one of her most recent artistic projects, the exhibition Tipping Point: Are We Creating Silence? on view at the Catalina Art Museum near Los Angeles through March 2020. Inspired by recordings of extinct birds (cataloged by the Ornithology Lab at Cornell University), Turk explores the extinction of birds in North America in a multipart interactive installation that includes a metal maze—made up of sculpted symbols highlighting attributes of the continent’s birds—in which visitors can consider their relationship with the birds represented and the loss of the songs of the extinct birds.

Says Turk: “Extinction as a concept, event as a conversation, overwhelms us so deeply that we remain silent.” Our silence, when faced with uncomfortable, difficult subjects, echoes the silence of our skies and parks and woodlands as we lose the birdsongs of more and more birds. In this poignant work, Turk uses her skills as a sculptor and her sensitivity to the natural world to highlight a very different type of absence—one that far outweighs any block of marble.

More about Elizabeth Turk’s work can be found at Elizabeth Turk