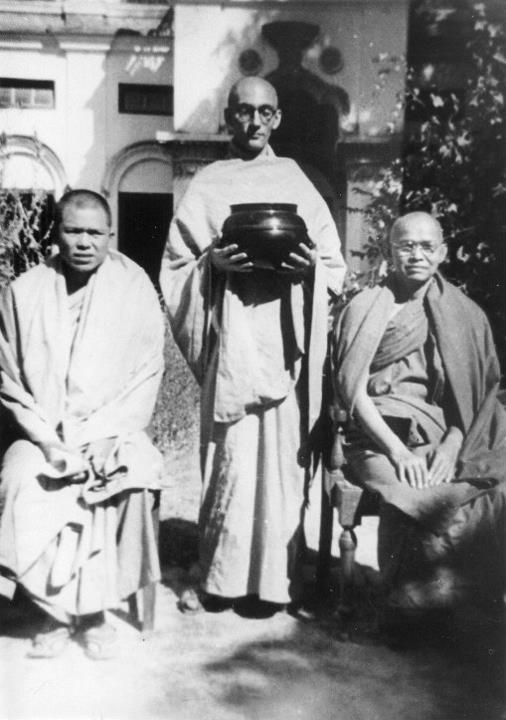

If the goal of Buddhism is nirvana, or at least to live a life based on Buddhist principles, how does the creation or consumption of art lead to, or away from, that goal? Few, if any, have discussed this with regard to ethics. To find someone who has, we have to go back to the 1950s, when a young Englishman with a penchant for poetry took up the yellow robe and found to his dismay that he would have to give up his writing, even going so far as to burn his poetry. Out of this inner conflict came four essays, collected in 1980 in The Religion of Art. The author was a young Sangharakshita, founder of the Western Buddhist Order.

His writing here seems to have been addressed to his need to reconcile his religious practice with his interest in the arts. His approach is two-fold. One is to appeal to authority by showing that the Buddha did not prohibit the practice or consumption of art, and even better still that the Buddha himself appreciated and expressed aesthetic qualities. The second is to demonstrate how art compliments, and may even replace, religious practice. Along the way he counsels those with both religious and artistic aspirations.

“Advice to a Young Poet” (1953) sets out a five-point program for the aspiring writer to nurture his personality and poetry. In “The Meaning of Buddhism and the Value of Art” (1956) extracts from the canon are presented to demonstrate the Buddha not only did not proscribe art, but was himself an admirer, and sometimes exponent, of aesthetics. With “Paradox and Poetry in The Voice of the Silence” (1958), Sangharakshita examines the titular literary devices as tools for expressing the experience of transcendence. And in “The Religion of Art” (1973) he pulls together many of these ideas to argue that the practice and appreciation of art is an activity with similarities to religion.

On the canonical evidence, Sangharakshita asserts the Buddha prohibited dance, song, instrumental music, and theatrical performances because they had no redeeming spiritual qualities. They were, in effect, pop culture of the day, “the ancient Indian equivalent of dance-music.” Most importantly, the Eighth precept cannot be generalized into a total exclusion of all aesthetic endeavors. He cites examples from three suttas to demonstrate the Buddha was not a puritan.

Regarding the similarities of art and religion, Sangharakshita draws a parallel between the artist living a life of continual renewal, of “perpetual progress, rather than … a definite arrival at a fixed point of achievement…” with the life of the Bodhisattva, who is reminded not to rest in dharmas or regard nirvana as a final attainment. The point of egolessness, for the artist and Bodhisattva, is an attitude toward states, experiences and attainments in which the aspirant is prepared to renounce all previous experience to embrace the new.

Lastly, Sangharakshita sets out an ethics for the spiritually-minded artist in which the serious aspirant must first renounce bad art, including newspapers, pulp magazines, tenth rate fiction, second and third rate poetry, religious lithographs, popular paintings, commercial calendars, and inartistic furniture, carpets, and crockery. The artist’s home is to be made of pleasing materials and located in a pleasant setting. He suggests the artist not take work that does not offer regular periods of rest. Prospects of “financial gain, … worldly advancement, and… social prestige” must be entirely abandoned. Commercial literary work must be avoided.

While some of this advice may seem sensible, it could also be taken the wrong way. It is not difficult to image someone producing brilliant, inspiring, life changing art while still living in relatively ugly surroundings and reading newspapers. The point he seems to be making is that the spiritual aspirant should whenever possible live with beauty and purity. The danger is in someone taking these strongly worded suggestions as requirements and perhaps making himself as miserable as the young Sangharakshita, who it will be recalled once burned all his poetry. Equally problematic is the contrast between “true art” and “bad art.” We may perhaps agree that good art is inspirational, but it does not follow that certain modes or genres can never be vehicles for inspiration. If the Buddha required 84,000 means of teaching, perhaps there is room for popular film, for example, as a vehicle for dhammic art.

As for the similarities of art and religion, on reflection we may note egolessness is available to anyone engaged in some form of activity, be it brick-laying or baking. Many of us have had the experience of being completely absorbed in work, and so it cannot be said this dissolving of self is unique to artists or Bodhisattvas. What sets the latter apart is an explicit regimen of practice intended to extend and deepen periods of egolessness. (Which of course means brick-laying could be an art so long as the layer carried out his house-building with the intention of deepening his experience of egolessness, leading us back to the Buddha’s 84,000 methods.) The question remains, for Buddhists, whether religious practice results in qualitatively different experiences of egolessness, and how art can contribute to the goal of nirvana.

While Sangharakshita’s canonical citations show the Buddha’s relation to art may be more complicated than the Eighth precept, they are not conclusive. How can we square Sangharakshita’s call to the artist to reach out and touch the world, with the Buddha’s call to leave the world alone? Even a casual reading of the texts may lead one to question whether consuming art is an abuse of the senses. This is, in fact, a recurring theme in English-language internet Buddhist forums and of great importance to modern Buddhists living in a media-saturated world. Perhaps more of them, caught between aestheticism and asceticism, will someday soon be exploring further the potential of art in Buddhist ethics.

Sangharaskshita. The Religion of Art. Cambridge: Windhorse Publications, 1980 (2012 electronic edition).