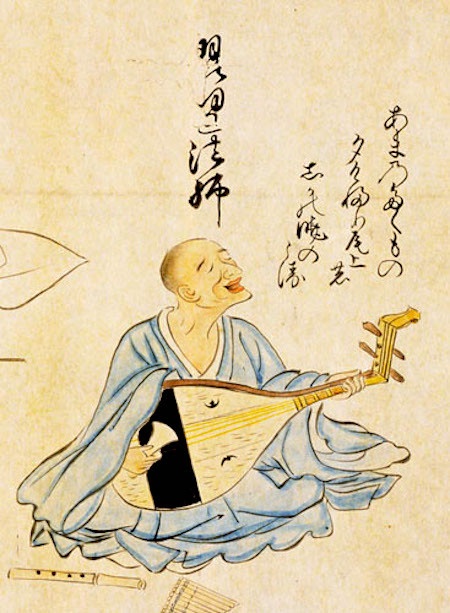

Heike. From ntj.jac.go.jp

In the last few weeks, I have been teaching the Tale of Heike (Heike monogatari) to my students at Luther College. The Tale of Heike is central to Japanese culture for a couple of reasons: first, it remembers and records a historically significant and formative event, namely the so-called Genpei war between the Minamoto family and the house of Taira (1180–85) that replaced the imperial court and the aristocracy of the Heian period (794–1185) with the Kamakura shogunate. Second, it has inspired and captured the Japanese imagination and Japanese literature ever since the first itinerant, blind monks known as “Dharma teachers with a biwa”* (biwa hoshi) recited, first, individual episodes of the events referred to as the Genpei war and, then, the collection of the Tale of Heike on the street corners of Kamakura (1185–1333) and Muromachi (1333–1573) Japan. It has influenced and is reflected in the narratives of puppet plays (bunraku), No plays, ghost stories (kaidan), Kabuki theater, as well as contemporary modes of storytelling, such as TV dramas, manga, and anime. Third, it opens a window on the way Buddhism was understood in Kamakura Japan and thereafter. To be clear, the Tale of Heike does not belong to the Buddhist canon or even the commentary tradition, but was created and instrumentalized by itinerant monks as an effective and entertaining tool to introduce and popularize some key Buddhist notions.

The story told in the Tale of Heike can be summarized rather quickly. It recounts Taira no Kiyomori’s rise to power after he helped the retired emperor Go Shirakawa to subdue the Hogen and Heiji rebellions in 1156 and 1159. He consolidates his power when his daughter Kenreimon’in is married by emperor Takakaku and, after his father is forced to retire in 1180, Kiyomori’s grandson Antoku becomes emperor at the age of two. Kiyomori himself is given the title of chief minister (daijo daijin). At this point, the head of an opposing clan Minamoto no Yorimasa declares war on the house of Heike. After some minor setbacks, Minammoto no Yoshinaka captures Kyoto and the armies of the Minamoto family under Yoshitsune defeat the house of Taira at the battles of Ichi no tani in 1184 and Dan no ura in 1185. The war ends when the Lady Ni, Kiyomori’s widow and the grandmother of the emperor, drowns herself and Antoku after the loss at Dan no ura, the remaining generals of the Heike are executed, and Kenreimon’in becomes a nun. After his victory, Minamoto no Yoritomo establishes the shogunate and moves the capital to Kamakura.

However, the story is not merely a historical narrative, but addresses profound religious themes. The story commences with the sound of the bell of Gion Shoja proclaiming the impermanence of everything and announcing the fact that even power and might do not last: “The proud do not endure, like a passing dream on a night in spring; the mighty fall at last, to be no more than dust before the wind.”** The war between the house of Taira and the Minamoto family symbolizes not only the cycle of death and rebirth (samsara), but also the age of the “end of the Dharma” (mappo). The war is caused by the desire of Kiyomori to establish and consolidate his power at any cost. The result of his striving for power is an untimely death and, ultimately, the destruction of his lineage and clan. Throughout the tale, the characters realize the futility of their investments in worldly matters and the transience of the this-worldly fruits the characters of the Tale of Heike desire. Realizing the impermanence of accomplishments, the inevitability of karmic law, and the vanity of egocentrism, various characters, such as the dancers Gio and Hotoke, Kiyomori’s grandson Koremori, the retired emperor Go Shirakawa, and Kiyomori’s daughter Kenreimon’in, renounce the worldly life, its desires, and its fruits to enter monastic life. The message is hard to miss: samsara is full of suffering caused by our desires, the vanity of egocentrism, and ignorance of the three characteristics or reality (trilaksana). The only escape from this predicament is monastic life. It is monastic life and devotion to Amida Buddha that opens the gates to the Pure Land and escape from suffering.

So far the Tale of Heike advances orthodox Buddhist teachings. What makes its message somewhat difficult to digest is the fact that the narrative not only seems to identify this life, samsara, with suffering, but in addition, death with liberation. Koremori goes so far as to commit suicide to attain release from samsara and the suffering it brings. Of course, in most Buddhist systems, the realm of suffering is not equated with “life” but with “death-and-rebirth.” If the inevitable consequence of desire, ignorance, and selfishness is “death-and-rebirth,” liberation from it cannot be death. Equally, the goal of many Mahayana Buddhist systems, even Pure Land Buddhist systems, is not the Pure Land but Buddhahood. This is the purpose of the bodhisattva vow—the vow to liberate all sentient beings—as well as the 48 vows of Amida Buddha. One could say that while the Tale of Heike succeeds in criticizing the delusion of egocentrism and the consequences of violence, it also seems to imply, at least at times, some kind of escapism. However, in the end, the text returns to the theme of impermanence. The passages on Amida’s vows and the birth in the Pure Land poignantly contrast the egocentrism of Kiyomori with the reliance of “other power” (tariki) that the initiates and novices exhibit. The story of Gio and Hotoke reminds us that there is an alternative to a life of greed and selfishness. But this alternative is not to be found in an escape from samsara but in altruism and compassion. This is the mission of the bodhisattva. This is what motivates the biwa hoshi to dedicate their lives to the collection and performance of songs that commemorate the plight of the Heike. This is also why, in Japanese folklore, the biwa hoshi have become a reminder of our transience and literature, and guides who call on us to look beyond ourselves and recognize the faces of those in need.

* A short-necked fretted lute, often used in storytelling.

** McCullough, Helen. Translated 1990. The Tale of the Heike. Stanford: Stanford University Press. (p. 23)