We all wish to maintain a sense of community when conducting teachings, work meetings, symposiums, or conferences. In the challenging year of 2020, we saw a significant shift toward online events. For the most part, I believe the online transition has been a positive trend. While nothing can quite replicate the physical presence of like-minded friends, going online opens the door to countless others who may have been unable to attend a gathering in any other way. This is especially true of religious gatherings, for which much more work is needed in being inclusive and mindful of how access can be restricted: physically, financially, and geographically.

On 12 December 2020, about 200 people from around the world came together from the comfort of their homes to listen to the wise words of respected teachers and examples of compassion in action, who were also able to join from wherever they were in the world. This was Sakyadhita Spain’s 2nd International Symposium of Spanish-Speaking Buddhist Women, which featured prominent names including the Gyalwang Drukpa’s “Kung Fu Nuns,” Ven. Karma Lekshe Tsomo, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, and Roshi Joan Halifax. The topic for the evening was climate change and the implications of Buddhist practice in the world. In the original Spanish, the conference’s title was: “Dharma-Gaia: budismo, mujeres y la crisis climática.” (“Dharma-Gaia: Buddhism, Women, and the Climate Crisis”)

There were some technical issues surrounding translation that may have initially been frustrating for some attendees, but that did not impact the core message of the evening: “the choice is ours.” That sounds somewhat simplistic, but there is plenty to unpack in this concept.

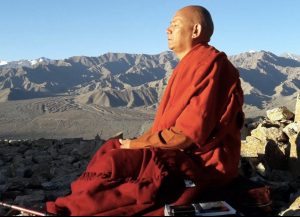

The first guest was Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, and in this article I will examine what she had to say.

The first question she was asked was: how, in this modern world, can we as Buddhists foster deep compassion and empathy toward all forms of life?

Jetsunma began by reminding us that as practitioners of Buddhism, one of the most basic meditation parctices is that of loving-kindness, which begins with the reflection: “All beings have been at one time or another in a position of our mothers,” and that: “all beings really does mean all beings.” That we should be fostering an ahimsa attitude, an ahimsa behaviour, and an ahimsa nature so that “all beings feel safe in our presence;” that there is interconnection at a profound level between humans, animals, insects, fish, and all of nature, even all botanical beings. We are interconnected at the quantum level, meaning that all actions send ripples through the web of collective energy, but as Jetsunma reminds us: we have been all of these living beings in one incarnation or another, and that any particular life would have been the most precious to us in any given lifetime.

“Every single being that we meet wants to feel good. Doesn’t want to be hurt. Doesn’t want to feel sad. And so that responsibility, just as we wish for happiness for ourselves, all beings wish for happiness for themselves. . . . Ethical conduct is based on that.” In adopting an ahimsa way of life, we refrain from harm in all forms. We do not partake in lying, stealing, or in any way the taking of life. That we remain kind and truthful and truly wish for the happiness of all. “This is very basic Buddhadharma. To transform ourselves from our usual egocentric thinking . . . to recognizing that we have this interconnection with all beings.” We must transcend our dualistic thinking and reside in the mind that holds this profound interconnection in awareness.

Jetsunma also made an emphatic plea for us to remember that this planet is so very precious and that we have a deep need to respect her. Again, that “we are all interconnected.” At this point I was reminded of the subterranean matrix of mycorrhizal fungi called mycelium, which extends plant roots through the earth and creates a super web, just like the internet but beneath our feet, for flora. Trees communicate with each other, care for each other, and mother trees will even look out for their saplings. We are reminded that the Earth will outlive us, yet “we are destroying the very thing that makes us who we are.”

“How can we use Buddhism to combat climate change?” was the next question. Simply put, “We have to think of how to live sensibly on this planet,” was the response. We are so fueled by negative emotions such as greed, anger, hatred, jealousy, and competitiveness that we must make a real conscious choice to live differently, more simply. We must cultivate a sense of contentment with what we have rather than lusting after more. To look at what we do as individuals and question deeply:

“What am I doing and what is my life for?”

The first thing we can do is to reduce our contribution to pollution and climate change, to look at how to reduce the methane produced, as well as to behave without hypocrisy. “As Buddhists who are endlessly talking about compassion and love and so forth, the very least we can do is to become vegetarian, and maybe even vegan . . . and walk our talk.” Our hypocrisy (in eating the sentient beings that we profess to love) is destroying our planet. How can we profess empathy and loving-kindness when we devour the suffering and fear of a dead animal sandwich who simply wanted to be happy?

It is also worth remembering that cortisol is released by stress, and that these animals are of course chronically and highly stressed by the time they are slaughtered. This remains in their bodies, which are then consumed by humans.

Increased affluence, Jetsunma pointed out, has resulted in increased consumption. This in turn has led to more land being used for raising cattle, which produces more methane that pollutes the atmosphere more than all the cars on the roads. Jetsunma’s advice continued in a pragmatic thread, one that I am in utter agreement over: “Live simply and grow your own food.”

Unfortunately for many of us, growing our own food is simply not possible or practical. Therefore, a great way around a lack of land can be growing seedlings on a window sill. Sprouted seeds are incredibly healthy and economical and can be grown with reverence. We must reduce our waste, Jetsunma continued. Recycling and upcycling are two paths that can make a significant difference. She asked us to consider: “How can I use my life to benefit the world . . . based on compassion, based upon loving-kindness?”

The choice is ours.

The question of people of power was then raised, with the charge that they typically do not act with the same care for the planet that many of us do. We were asked to imagine a dark fog of negativity enshrouding the world. Plugging into this fog, leeching off it or feeding into it with more negativity, will do nothing but help it grow and we must avoid that. We must make the conscious effort to transmute the foul into something positive. We must be the candle in a dark room. Some of the most powerful people are the most troubled and in need of our compassion. Jetsunma therefore urged us to remain in truth and nonviolent action and not to feed into hatred, because ultimately “truth is more powerful than lies.”

When asked what we can actually do, Jetsunma reminded us to teach—specifically, to teach our young that there is hope. Teach them lessons in values, compassion, mindfulness, and ecology. Teach them to use common sense. “We need to have common sense about our lives . . . we should stand for what is true and what is right . . . and not be hypocrites. If we believe something, we should do it. . . . And reach out with compassion and kindness.”

“Cultivate a good heart,” as the Dalai Lama encourages us. Basic goodness is what the planet needs. Being a good human being is what counts. Jetsunma reminded the audience: “All beings have Buddha-nature. All beings have the potential to awaken,” and it is this potential that connects us since we all share it. We are only separated in an illusory way thanks to our dualistic thinking. We view the external world and activities as less significant to us when they appear to have no benefit to us rather than how each one of us, each being, is an essential part of the Great Symphony. And we each have our part to play in this Great Symphony: “It’s not about male or female. It’s about living in this world responsibly, with respect for all beings.”

In my next article, I will discuss the reflections shared by Roshi Joan Halifax during this symposium. With much gratitude to Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo and Sakyadhita Spain for hosting the conference!