Due to Buddhism’s long presence in Asia and beyond, it is commonly thought that the religion has always been a well-received movement and has not faced much opposition or oppression. Aside from some occasional persecutions by anti-Buddhist rulers, many are under the impression that Buddhism has always enjoyed momentum and is spreading successfully around the world.

In Russia, Buddhism is not the most popular religion, but as one of the nation’s historical faiths, the government officially acknowledges it as a crucial part of the cultural and religious landscape. One might think that it is flourishing, but two recent lectures by Professor Alexey Maslov give one pause for thought. These two lectures were titled “Buddhism in Russia: Introspection of Spirituality and New Modalities” and “Buddhist Studies in Russia: Academic Traditions and New Research.” They were presented at The University of Hong Kong on 18 and 19 April, respectively, and provided a fresh viewpoint on the development and status of Buddhism in Russia over the centuries. The talks were part of the 20th Anniversary Series of the HKU Center of Buddhist Studies (CBS).

Prof. Maslov has authored more than 20 books, including translations of Buddhist texts, and is a renowned expert in Russia on Asian and Chinese studies. He is also a government expert on Russia’s relations with East Asia and a visiting professor at various Chinese and European universities. He is a Chinese Buddhist and spent more than two years as a monk in China’s famous Chan Shaolin Temple.

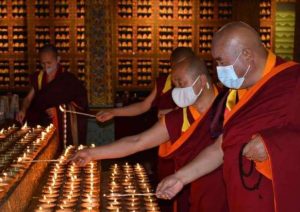

In his first talk on 18 April, Prof. Maslov discussed three core aspects of Buddhism as practiced in Russia: institutionalized Buddhism, which consists of traditional (mostly Tibetan and Mongolian Buddhist) communities organized into various associations; non-systematic groups, which encompasses Mahayana (Zen and Chan Buddhist groups) and Theravada; and everyday Buddhism, which emphasizes activities such as meditation that are popular among younger people. Prof. Maslov then highlighted the main Buddhist regions (autonomous republics) in Russia: Buryatia, Kalmykia, and Tuva. In this regard, the traditional religion of the Buryats, Kalmyks, and Tuvans in Russia is Buddhism. Vajrayana Buddhism, also popularly known as Lamaism in Russia, is the denomination of all Buddhist groups in these republics.

Buddhism was introduced to Russia in the 17th century from Mongolia by Kalmyk tribes, who later settled in the northern Caspian region in the area of present-day Buryatia. There is allegedly a reference to Buddhism in a 1741 decree issued by Empress Elizaveta Petrovna (1709–62), which is regarded by many scholars as the first state recognition of Buddhism in Russia. This decree essentially acknowledged the Russian citizenship of the Buddhist clergy, gave them legitimacy, and provided them with some rights, which might be taken as an indirect acknowledgement of Buddhism in Russia. Empress Petrovna was given the name “White Tara” by Buddhist lamas as a result of her acknowledgment.

Buddhist communities today are active in significant Russian cities, with the majority of them centered in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. As Prof. Maslow noted in his lecture, Theravada, and Mahayana Buddhism are also practiced in Russia. A small percentage of Buddhists practice the Thai school. When asked to elaborate on Theravada Buddhism, Professor Maslov noted that there are no Theravada monks in Russia.

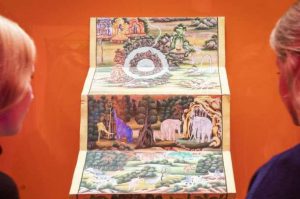

According to Prof. Maslov, the fate of Buddhism in Russia has always been strongly tied to the political goals of the state. In the early part of the 20th century, political events in the Soviet Union were connected to the suspension of study on Buddhism and the persecution of the Buddhist faithful. Government officials started to forcibly disrobe monks and subsequently demolish Buddhist temples as part of anti-religious Communist policies. Hundreds of Buddhist clerics were arrested and locked up. Physical violence was rife. Monasteries and temples in Buryatia and Kalmykia were mostly destroyed senselessly in a fit of anti-religious fanaticism. The few that were spared were utilized for other purposes. Most of the possessions of Buddhist temples were ransacked and looted, either kept as stolen property or found their way to museums. As a result, Buddhist culture was declared extinct in Buryatia and Kalmykia during the Soviet period.

With religious freedom re-established after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of Soviet Russia, a Buddhist resurgence began shortly after 1991. It was surprising that a national Buddhist revival was quite visible in the context of a new but nominally secular Russia. Buryatia, Kalmykia, and Tuva experienced a rapid revival of interest in their people’s Buddhist roots. A new paradigm of collaboration between the state and religious institutions was developed by the government. This model was created largely to legitimize state policies and control ethnic tensions through interfaith dialogue.

Prof. Maslov noted that Orthodox Christianity has a distinctive place in the history and life of modern society, since Russia is a multi-confessional state with different religions. He said that there was an extensive list of books by Orthodox authors that criticized Buddhist ideas. Orthodox criticism of Buddhism serves to highlight Christianity’s dominance over non-Christian religions, portraying Buddhism as a “outsider” in society.

Prof. Maslov also asserted that Buddhism has grown in a way that is not directly tied to the nation’s history. According to him, there is a movement among atheist academics and the scientifically minded public to view Buddhism more as a philosophical system than a religion, much as how Buddhism is seen by many in the mindfulness industry. This point was mostly highlighted in his second talk on 19 April. The key periods of Buddhist Studies in Russia (or more accurately, the Saint Petersburg school of Buddhist Studies) were also discussed.

Beginning in the early 18th century, one of the earliest areas of “Oriental Studies” in Russia was Buddhism. This academic priority had a strong influence on the state’s policies. It was essential to acquire and utilize Buddhist studies in addition to the Mongolian and Buryat languages due to the neighboring regions and the expansion of Russian power. However, Prof. Maslov observed that early on in the Russian academic study of Buddhism, researchers mostly focused on Indian Buddhism.

Prof. Maslov highlighted certain academics who have made significant contributions to the study of Buddhism, such as Fyodor Shcherbatskoy (1866–1942), a distinguished Russian Indologist credited with laying the groundwork for the Saint Petersburg school. However, Prof. Maslow said that the majority focused on building on the work French and German Buddhologists rather than their Russian counterparts, influencing what the Saint Petersburg school considered authoritative.

It is apparent that successive governments of post-Soviet Russia have mostly favored the revival of Buddhism, along with other national religions. Tibetan, Japanese, and Chinese Buddhism continue to be the primary fields studied by Russian scholars. Prof. Maslov highlighted some of his own contributions on Zen Buddhism. However, the Saint Petersburg school continues to be small, with few academics interested in Russian Buddhism (aside from some lamas and scholars). Hopefully, he noted, this gap will be filled in the future, since new generations of academics have begun emerging from local Buddhist communities.

Related features from BDG

From the Kalmyk Steppe to the Open Plains of 3D Virtual Reality: The Lost and Found Buddhist Temples of Kalmykia

Buddhism in Kalmykia: Construction of a Stupa as a Symbol of Unity

A Kalmyk Village Through Time: Buddhist Lore and History in Tsagan Aman

The Kalmyk Temple of Victory: Survival of Buddhism on the Volga

Related news from BDG

Telo Tulku Rinpoche, Supreme Lama in Russian Republic of Kalmykia, Announces Resignation

Mongolian Kanjur from India’s Ministry of Culture Distributed in Russia

Only Buddhist Monastery in Ural Region of Russia Demolished