The one who praises you is a thief.

(Robert Aitken)

The one who criticizes you is your true friend.

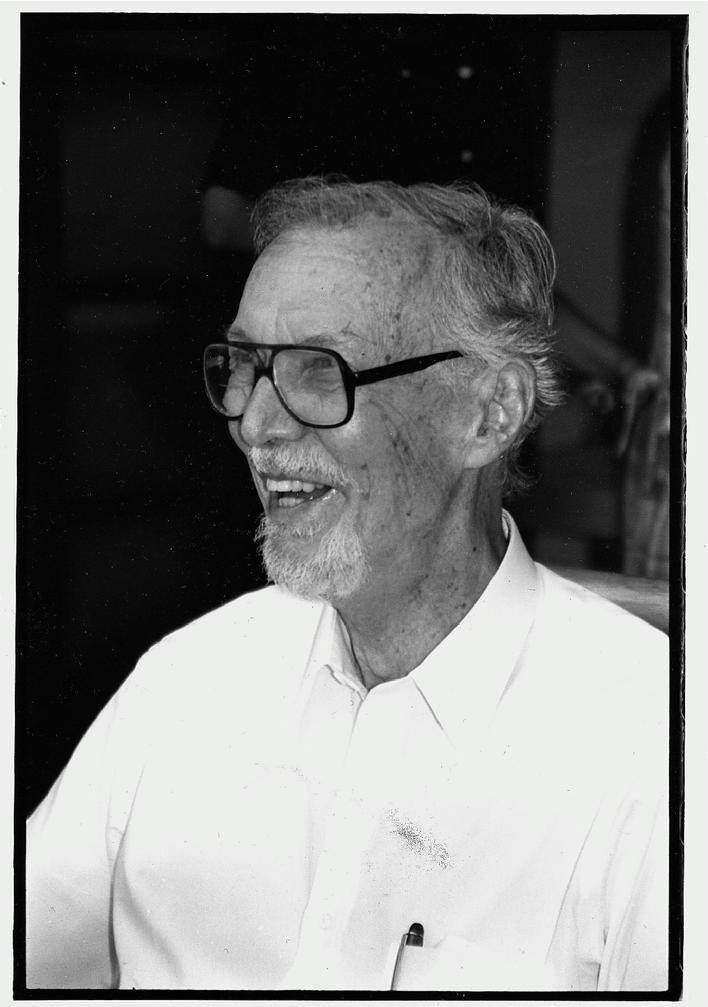

Although the Honolulu Diamond Sangha would eventually spread around the world (it birthed affiliate Zen centers in Australia and New Zealand, Europe, South America, and the United States), the initial founding of the Hawaii center in 1959 had a most modest beginning. Only four people were present for the opening: a man called Robert Aitken, his wife Anne, and two friends. Their first meetings were in the Aitken living room. Sofa cushions were used as meditation zafus, and for a meditation bell they struck a glass bowl with a wooden spoon. Considering the influence Aitken was to wield in the future, this was an almost ramshackle start.

Robert Aitken was born in Philadelphia on 19 June 1917. When Robert was five years old, his parents relocated to Hawaii, a place he would always regard as his home. Just before the start of the Second World War, Aitken was living and working on the Pacific island of Guam. When war erupted and the Japanese military took control of the island, Aitken was taken as an enemy national to be interned in Kobe, Japan. There, one of his guards discovered Aitken’s interest in Japanese literature and culture, and loaned him a copy of the recently published book Zen in English Literature (1942) by the British-born Japanophile, Asia scholar, and influential professor and poet, R. H. Blyth. Aitken would later reflect that he was fascinated by the point of view expressed in the book. He claimed to have read it over and over, perhaps 10 times, and stated that the book made him “absurdly happy despite our miserable circumstances.”

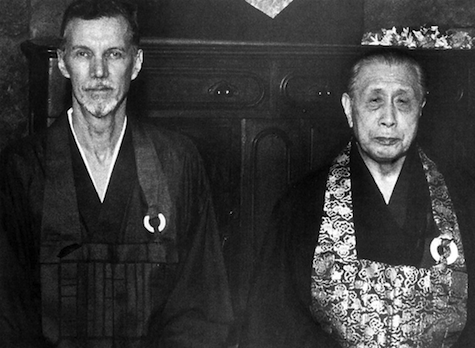

When several internment camps were combined in 1944, Aitken was astonished and delighted to discover that Dr. Blyth was among the additional new internees. “For the next 14 months, until the war was over I learned much about Zen from this creative teacher,” Aitken would write later on. Aitken became determined to undertake further Zen studies under the guidance of a Japanese roshi as soon as the opportunity presented itself.

When the war ended, Aitken returned to Hawaii, and earned an undergraduate degree in English literature and an MA in Japanese from the University of Hawaii. He traveled back to Japan in 1950 when he received an academic grant to study Japanese literature. While there he began more serious study of Zen philosophy and practice as well. Ironically, his commitment to the Zen path was tested severely in Japan. To his dismay, he discovered that most of the Zen centers were equivalent to hereditary estates for young men training to take over their fathers’ temples. Furthermore, Japan’s vast network of Zen temples was simply engaged in generating finances by being paid to offer ritual ceremonies at funerals. Meditation was rare and difficult to find in most temples. Then, there was also the personal mistreatment he experienced being struck with a keisaku (Zen stick) by young Japanese monks angry at him as an American for Japan’s war loss. At the end of one lengthy retreat, a senior monk attempted to humiliate Aitken by lifting his meditation skirt, publicly ridiculing him for not sitting in full lotus posture. Nevertheless, it was his deep desire to follow the Zen path that empowered Aitken to remain, absorbing as much as he could in order to bring it back to others.

After years of study in Japan and Hawaii, Aitken and his wife Anne opened their home to a sangha. Together they created a warm, inviting atmosphere for meditation, discussion, and learning. In fact, a couple traveling through Hawaii experienced automobile problems in front of their Zendo (Zen training center). They came in asking to use the telephone and ended up remaining as students for six months.

Aitken not only taught Zen but clearly applied its teachings in his own daily life. An example of this personal application revolves around the Zen teachings concerning mindfulness: bringing nonjudgmental awareness to one’s experiences. In a book of his selected writings after his passing, titled Miniatures of a Zen Master (2008), one can read what Aitken wrote about “Dad’s Indiscretion.” His father had been an anthropologist who conducted research on small island in French Polynesia. Sometime between 1920 and 1922, he came down with a very serious virus and had to be hospitalized. Aitken recalls: “During his convalescence, apparently just once, he slipped into bed with his caregiver. More than half a century later, after he had lived out his life, my brother found a letter in Dad’s papers that indicated we had a half-sister named Tahina.” Rather than judging, blaming and experience shaming, Aitken and his family responded without judging. In fact, he writes that the family “were delighted to know we had another sister.”

The Aitken family then traveled to the island to meet and get to know their newly discovered sister. “We visited Tahini and her nine children and their innumerable grandchildren. Many of them visited us in Hawaii, and Tahina’s youngest grand daughter, as of this writing, is attending the University of Hawaii.” Here is how he concluded that story: “One indiscretion and—wow!”

As Aitken’s teachings attracted more students, many of his lectures were transformed into popular Zen books including Taking the Path of Zen (1982) and Mind of Clover: Essays in Zen Buddhist Ethics (1984). In addition to teaching and writing, Aitken was a vocal pacifist and social activist. He spoke out against nuclear testing, was an outspoken critic of the Vietnam War, and opposed the nuclear arms race raging at the time between the United States and the Soviet Union. In addition, Aitken was an early promoter of equal rights for women and, in 1978, was a founder of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship.

Robert Aitken died after a brief bout with pneumonia on 5 August 2010 in Honolulu, Hawaii.

His final book, The River of Heaven: The Haiku of Basho, Buson, Issa, and Shiki was published shortly after his death in 2011.

Words of wisdom from Robert Aitken

Hatred is a poison that permanently sets people apart, smothering any possibility of compassion.

We are all of us interrelated—not just people, but animals too, and stones, clouds, trees. What a mess we have made of the precious net of relationships.

Do the best you can and no more will be asked.

Our habits of consumption support massive and irredeemable exploitation of people, animals, trees, earth, water, and air.

Our practice is not to clear up the mystery. It is to make the mystery clear.

All of us fear failure, to some degree or another, and prefer not to try something that seems too difficult. However, it is important to understand that Zen training is also a matter of coping with failure.

I have heard it said that all paths lead to the top of the same mountain. I doubt it.

When you are driving a car, just drive. When you answer the telephone, devote yourself to the caller. Likewise, move from circumstance to circumstance with this same quality of attention. Practice awareness.

Anguish is everywhere. Release from anguish comes with the personal acknowledgment and resolve: we are here together very briefly, so let us accept reality fully and take care of one another while we can.

In a deeper and yet more ordinary dimension, all of us are Buddha. We haven’t realized it yet, perhaps, but that does not deny the fact. Our practice is not to clear up the mystery. It is to make the mystery clear.

Related features from BDG

Nyanaponika Thera: Buddhist Monk and British Prisoner of War

The Man Who Brought Buddhism to Great Britain: Allan Bennett

Julius Goldwater: Protector of Japanese American Buddhists

Book Review: Poetry and Zen: Letters and Uncollected Writings of R. H. Blyth

Thank you for this lovely piece about Aitken Rōshi. Question: where is the excerpt at the end, “Words of Wisdom from Robert Aitken,” taken from?