photos by Joe Tymczyszyn

Circumambulation, and traveling over ancient traces are two of the oldest extant ritual acts, characteristic of Buddhist and Hindu pilgrimages since antiquity. The adventurous Chinese scholar-monk Xuanzang in the seventh century did just that: he followed the sacred traces of former masters back to India, and then onward throughout India, sometimes staying, living with monks, sometimes revitalizing interest in forgotten sacred sites and discovering texts, usually circumambulating where he visited.

Even doctrinaire Buddhists like Xuanzang, who were not inclined to art or artistic ritualization, obediently followed these ancient traces and circumambulated relics, uniting devotion, ritual action, sacred geometry, and continental landscapes. Indeed, elemental archetypical actions tempered and tested by the harsh climates and topographies revealed the character of these devout men and women.

Where the Buddha was born, where he lived, where he taught, where he spread his metaphysical presence—all these trace out a devotional map for an unforgiving path through India and the Himalaya to China and back again. Circumambulating mountains, relics, bones, teeth; and finally stupas, mummies, treasures, and whole monasteries, was part of a geomantic ritualized lifestyle of Bon and Vajrayana monks and the communities they served. This behavior of circumambulating mountains and lakes is prehistoric; as old as the worship of these landmarks that were revered as deities. Vajrayana Buddhism adopted many archaic Tibetan ritual features, as well as Vedic traditions from India. Much of the ritual basis of Buddhism is far older than Buddhism itself, calling to mind the adage, “Inside every religion is another religion.”

These ancient rituals were conceived on a vast scale. Weeks of ritual action involving sand mandalas, thangka paintings, empowerments, butter sculptures, and ritual dance were performed in private before any public ritual transformed the local landscape, essentially bringing the deity forth for all. Forming circles of protection is archaic and tribal. Demarcations on a landscape define territory by spiritual energy and sacred geometry as much as by topographical configuration and military strategy

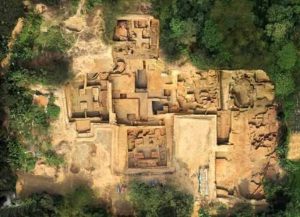

A circle is a kora. The Chorten Kora in Bhutan is a famous three-day circumambulation of a great chorten at Trashiyangtse. The Khilkor Kora is a four-hour monastic circling ritual around a large sand mandala in Tashichho Dzong. The Bon Kora of Wenjia Bonya monastery in Qinghai is a great processional circumambulation along the mountainside by the monks and villagers of Bonya. It is not for the fainthearted. Please enjoy here a series of photographs of the Bon Kora at Bonya Monastery in 2018 by Joe Tymczyszyn.

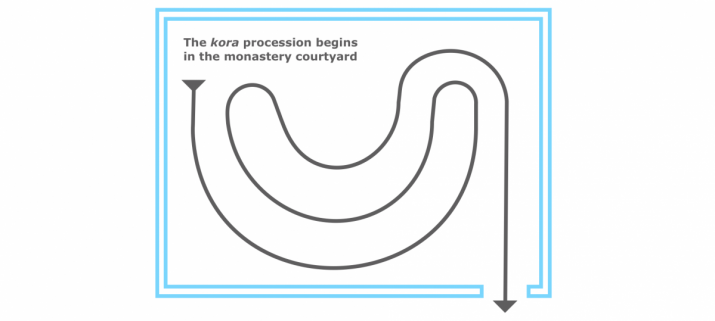

For a sense of the scale, please note the large Maitreya Buddha sculpture on the mountain above the monastery in the second photograph. The kora, popularly called the Maitreya Kora, moves from the monastery as the center of the circle. The entire monastic body comprises lamas, musicians, drummers, chanting monks, and monks with banners, flags, standards, and incense. At first breaking their circle in the courtyard that marks the center of the kora, their procession traces a design of multiple inverted semi-circles in the courtyard before heading down a precarious rocky slope and embarking to trace a great counter-clockwise circle on their stony homeland.

First down then up the mountainside to reach the Maitreya statue, the kora continues circling Maitreya until a full circle on the mountain has been completed and the monks return up the steps into the monastery.

Bon and Buddhist ritual have become syncretic over the centuries, initially with Tibet’s indigenous beliefs shaping the practices and beliefs of Vajrayana. The Bon Kora circumambulates in a counter-clockwise direction, echoing the direction of the Bon swastika’s movement. This is characteristically Bon and unlike Buddhist circumambulation, which moves clockwise. The Bon retain unique deities, archaic practices including dance, and a variety of monastic, semi-monastic, and hereditary lay practitioner vows.

This circumambulation requires nearly three hours for everyone to complete, and traces an enormous protective circle on the Bonya landscape. Perhaps most revealing, these enormous ritual acts demonstrate the complete spiritual integration of the monastic community, the lay community young and old, the physical landscape, and the cosmos itself. The exertion, the vibrating world, is visceral. Old people do not fail to mark the ancient traces. Helpful people push them along, invisibly assisting their climb or descent. I know; younger people pushed me along and even saved me from a few tumbles.

It is finally a self-similar nesting. The Dharma is in the monks and laypeople. Monks and laypeople embody Buddhist rites. Buddhist rites are settled in the monasteries. Monasteries are situated in the landscape’s mountains and valleys. Mountains and valleys join Earth and Heaven. All sits in cosmic perfection, the microcosmic orbit of the kora mirroring the macrocosmic orbit of the cosmos. Over some weeks, punctuated by a great day of circumambulation, a spiritual community reaffirms its place in the universe.

Another archaic practice is the display of sacred pictures to teach. This was originally a practical matter. A drawing could be made in the dirt, or if on paper or cloth, rolled up and carried. It could be unrolled and the lesson given another day in another place. Over time these sacred images became painted caves, became fine works of art, and became ceremonial embroidered thangka, sometimes monumental in size. Practical information such as scenes from the life of the Buddha were depicted, along with symbolic information such as protective deities.

With bold changes in metaphysics and cosmopolitanism as Buddhism became more a philosophical and intellectual religion, iconographic symbols played various roles from instructing a meditator how visualize, to asserting the abstract dominance of a Buddha to come. Indeed iconography was sectarian, and the sects were territorial.

Please see here another set of images of thangka “sunning,” combining two splendid ceremonial displays at the opulent Wu Village Lower Monastery, and another at the more humble Gomar Monastery, both in Repkong. These displays followed a monastery temple circumambulation of the mammoth embroideries, possible only when all the young men join to carry it. From there it is taken to a prepared mountainside, and Maitreya completes his evolution from concept to image to monumental embroidered thangka, and on to circumambulation and mountainside spectacle.

Photographer Joe Tymczyszyn has captured the engagement of the entire community. A compelling image is one of faith: the women of Gomar village standing in quiet awe and respect before the unfurled thangka of MaitreyaBuddha.

In all the color and splendor, the appeal to tourist photographers, and the increase in tourist numbers it implies, it is easy to forget that these large, archaic, weeks-long rituals are dedicated to belief and tradition. Whatever else can be said about the fate of Buddhism in contemporary China, it is evident that faith and tradition remain, on a grand and ancient scale, involving whole communities. This expression, a performed iconography of circles and images, shines out over vast reaches. A ritualized day, involving everyone and crying out to the skies, re-consecrates these places as Buddhist landscapes.

See more