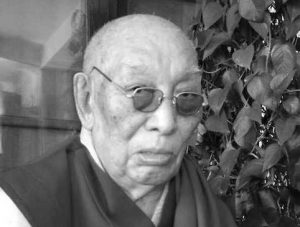

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891–1956) was a prominent leader of India’s “Untouchable” castes in the years leading up to Indian independence and the chief architect of the nation’s constitution. Known as “Babasaheb” among a large number of new Buddhists from the Mahar and other Scheduled Caste communities today, including young professionals and workers, Dr. Ambedkar is celebrated as one of India’s most educated individuals. He is revered as a fatherly figure, having held many roles, such as lawyer, legislator, author, labor leader, cabinet minister, and educator.

Dr. Ambedkar is also considered a “bodhisattva” by his followers, one whose memory continues to inspire the daily salute of “Jai Bhim!” (Victory to Ambedkar!) Educated at Columbia University in New York, where he received MA and PhD degrees, as well as at the University of London, where he obtained MSc and DSc degrees, Dr. Ambedkar was also admitted to the Bar in London and pursued postdoctoral studies at the same university.

Dr. Ambedkar was fortunate to have supportive parents who had high aspirations for his future. He credited the Buddha; Mahatma Jotiba Phule (1827–1890), a Maharashtrian social reformer who established the first Indian School for Untouchables; and the poet-saint Kabir (1440–1518), known for his rejection of caste and belief in universal brotherhood, as the primary influences on his ideology.

Dr. Ambedkar faced discrimination in school as an Untouchable, with restrictions on handling his notebooks and drinking water poured into his mouth from above. After high school, he was given the Life of Gautama Buddha (in Marathi) by K. A. Keluskar, a renowned author and social reformer. Understanding the Buddha’s staunch opposition to the caste system, Dr. Ambedkar advocated for the rights of all individuals, regardless of their caste, to become monastics. This is reflected in Dr. Ambedkar’s article “Buddha and the Future of His Religion” (1950).

Dr. Ambedkar witnessed caste-based violence and recognized the necessity for a social revolution with broad support to combat prejudice in India. Subsequently, during a political assembly of the Untouchables, Ambedkar stated:

My heart breaks to see the pitiable sight of your faces and to hear your sad voices. You have been groaning from time immemorial and yet you are not ashamed to hug your helplessness as an inevitability. Why did you not perish in the prenatal state instead? Why do you worsen and sadden the picture of the sorrows, poverty, slavery and burdens of the world with your deplorable, despicable, and detestable miserable life?. . . If you believe in living a respectable life, believe in self-help, which is the best help!

(Dhananjay 1954, 60)

In 1935, recognizing the deep-rooted inequality and injustice faced by Untouchables within Hinduism, Dr. Ambedkar made the decision to renounce the Hindu faith. This pivotal moment was reflected in his influential book Annihilation of Caste published in 1936. It was his unwavering dedication to combating caste-based discrimination that ultimately led him to embrace Buddhism on 14 October 1956. Prior to his conversion, Dr. Ambedkar extensively studied various religions, meticulously comparing their teachings and principles. After careful consideration, he concluded that Buddhism stood out as the most compassionate and just belief system. In his view, Buddhism alone offered a path toward true human welfare, prompting his historic conversion.

During the inaugural World Fellowship conference in Sri Lanka in 1950, Dr. Ambedkar raised concerns regarding the prioritization of fellowship over outreach and sacrifice within the Buddhist community. Upon his return to India, Dr. Ambedkar wholeheartedly committed himself to the promotion and rejuvenation of Buddhism. He authored papers, delivered lectures, engaged in conferences in Burma, established the Indian Buddhist Society, and finalized his book on the subject.

In 1955, Dr. Ambedkar made the decision to convert to Buddhism after finishing his book The Buddha and His Dhamma in the following year. This coincided with the 2,500th anniversary of the Buddha’s parinirvana, a global celebration. On 14 October 1956, the conversion ceremony took place in Nagpur, India—a date of significance due to Emperor Ashoka’s own embrace of Buddhism. Around 500,000 Untouchables joined Dr. Ambedkar and his wife in taking refuge in the Three Jewels and pledging to uphold the Five Precepts. The ceremony was presided over by Venerable Chandramani Mahathera (1875–1972), the oldest Buddhist monk in India. True to his vow made 21 years earlier to not die as a Hindu, Dr. Ambedkar passed away six weeks after his conversion.

The Buddha and His Dhamma was published in 1957. The text is considered scripture by followers of Dr. Ambedkar’s interpretation of Buddhism. However, some traditional Buddhists have found it difficult to understand his interpretation of Buddhism. Dr. Ambedkar interprets the Four Noble Truths:

His Dhamma had nothing to do with life after death. Nor has his Dhamma any concern with rituals and ceremonies. The centre of his Dhamma is man, and the relation of man to man in his life on Earth. This, he said, was his first postulate. His second postulate was that men are living in sorrow, in misery and poverty. The world is full of suffering and that [discovering] how to remove this suffering from the world is the only purpose of Dhamma. Nothing else is Dhamma. The recognition of the existence of suffering and to show the way to remove suffering is the foundation and basis of his Dhamma. This can be the only foundation and justification for Dhamma. A religion which fails to recognise this is no religion at all. . . according to his [Buddha’s] Dhamma if every person followed (1) the Path of Purity; (2) the Path of Righteousness; and (3) the Path of Virtue, it would bring about the end of all suffering.

(The Buddha and His Dhamma, 116)

In the subsequent sections of the book, the Path of Purity is identified as the traditional Five Precepts, the Path of Righteousness is identified as the Noble Eightfold Path, and the Path of Virtue is the traditional paramai (perfection), including the four brahma viharas. Dr. Ambedkar described nibbana as a “kingdom of righteousness on Earth.” Some believe his understanding of Buddhism underwent a significant change in focus and essence.

Richard W. Taylor compares Dr. Ambedkar’s compilation of The Buddha and His Dhamma to his work on the Indian Constitution, with its borrowings from American, British, and Indian law. As Taylor says:

[Ambedkar] has taken what seemed to him the most relevant of several Buddhist traditions edited them, sometimes drastically, added material of his own, and arranged them in an order. Like the Constitution, this too has become much more than another document. Just as the Constitution is at the heart of the nation’s political life, this canon is at the heart of the religious life of the new Buddhists.

(Queen 1996, 56)

Anand Kausalyayan translated and checked The Buddha and His Dhamma from English to Hindi, affirming that Dr. Ambedkar’s work was a new perspective, not a misrepresentation.

Dr. Ambedkar’s struggle for freedom encompassed all aspects of human life, including individual, communal, and the caste-based and religious communities in India. His development of socially engaged Buddhism was an expression of religious belief rather than the creation of a new religion. Dr. Ambedkar’s deep connection to the Buddha and his teachings grew stronger throughout his life, providing a sense of identity and hope to millions of his low-caste followers in India. The next generation of Buddhists gained a new outlook on social activism from his teachings.

Dr. Ambedkar’s legacy extends beyond the Dalit community, impacting the entirety of Indian history and the resurgence of Buddhism in the country. In 1990, on the centenary of his birth year, the government of India bestowed on him the prestigious “Bharat Ratna,” the highest civilian award in the nation.

* This tribute serves as a reminder of the profound impact of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, born on 14 April 1891. His contributions continue to inspire and guide us toward a more inclusive society.

References

Keer, Dhananjay. 1954. Dr. Ambedkar: Life and Mission. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan.

Queen, Christopher S. 1996. “Dr. Ambedkar and the Hermeneutics of Buddhist Liberation.” In Engaged Buddhism – Buddhist Liberation Movements in Asia. Edited by Christopher S. Queen and Sallie B. King. Albany: State University of New York Press, 45–71.

See more

Buddha and His Dhamma. E-book uploaded by Siddhartha Chabukswar (Internet Archive)

Related news reports from BDG

The First B. R. Ambedkar Statue Erected in the United States Unveiled in Maryland

Thousands of Dalits Embrace Buddhism in Gujarat on Birth Anniversary of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar

India Honors Dr. B. R. Ambedkar with New Statue, Circuit Train, and Calls for Social Change

Related features from BDG

Living Dr. Ambedkar’s Vision

An Ambedkarite Buddhist Today

Ambedkar in Seattle: The Annihilation of Caste