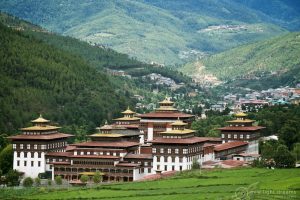

Walking around Lalitpur Metropolitan City (historically known as Patan) in the Kathmandu Valley is like stepping into a city-sized museum in which life and art are inseparable. The ancient architecture is one of awe-inspiring beauty, especially around the main Durbar Square, although many structures are still being rebuilt following the devastating earthquakes of 2015.

The streets and narrow alleys are dotted with centuries-old temples and stupas covered with offerings of vermillion and marigold, and jostling for space with shops and studios selling traditional and modern art, notably thangkas (scroll paintings), mostly rendered in the Tibetan style.

Art is everywhere. It is hard to miss the vibrant Buddhist motifs and symbols on home exteriors, especially doorways. It is a very old tradition: the traveling Chinese monk and translator Faxian (337–c. 422), who came to India and Nepal at the turn of the fifth century, noted how the walls of the houses in Kathmandu were decorated with colorful art.

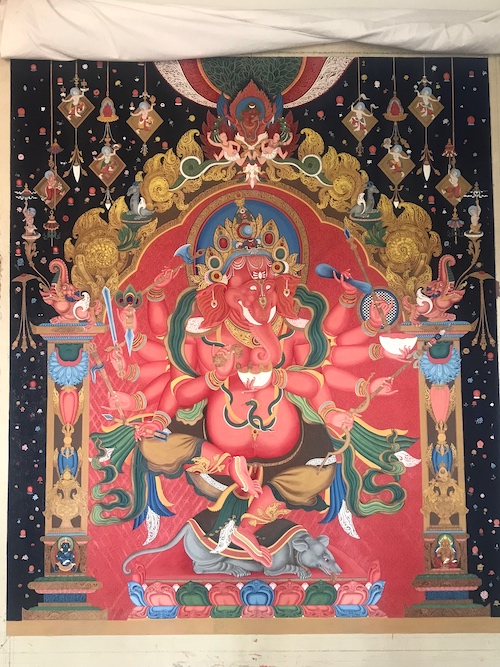

The Nepalese have had a greater influence on Tibetan art than the latter has had on the former, but there is a “pizza effect” happening here: the original Newari art, it seems, has been eclipsed in no small measure by new “Tibetanized” avatars. And one can be forgiven for wanting to know more about the traditional art of the Newars, the natives of the Kathmandu Valley I went to meet with Lok Chitrakar, an artist who has been working hard to revive Paubha (the traditional Newari art), which are often visual representations of Hindu and Buddhist philosophies as practiced in the Vajrayana tradition.

I walked the dusty streets toward Patan Doka, the city’s main entrance. As soon as I reached there, I attempted to verify my position with Google Maps, yet the app was not to be fully trusted and I was unsure whether I was heading in the right direction. Just at that moment, I saw a slender person walking toward me. I asked him for directions, and he responded in a softly toned voice: “You are asking the right person. I am Lok Chitrakar! You can come with me.” We walked past Patan Doka before taking a left turn into an alley. Chitrakar’s studio, Simrik Atelier, is on the second floor of a nondescript building. Inside, his students were busy working on their canvases, painting various tantric deities and exotic images.

Chitrakars—a caste within the Newar community—are, as the Sanskrit word suggests, painters. Born in Kathmandu, Lok Chitrakar grew up surrounded by art. A self-taught artist, he was painting professionally by age 12. His father died young, leaving the family in some distress to make ends meet. But Lok was not one to give up: he moved to Patan at the beginning of his career and began to promote his art from shop to shop. Some shopkeepers were rude to him, but that failed to discourage Lok. Gradually, over the years he has received much-deserved recognition. He traveled (spending nearly two years in Japan). Stories about him began to appear in newspapers in Nepal and abroad, and he held exhibitions, some of them graced by members of the Nepalese royal family.

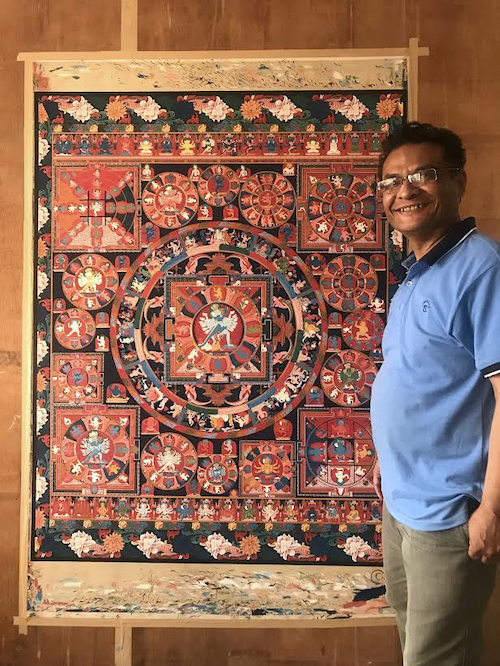

Lok’s self-effacing nature, coupled with his lack of interest in commercial success, however, has led to awkward circumstances. He was once sent a clipping from a Japanese newspaper: his sponsor there had decided to place a newspaper advertisement for the sale of Lok’s work—which he had produced for free—for an exorbitant sum. Lok is not commercially successful, it seems, more perhaps by design than anything else. For one, he works extremely slowly. In his studio he showed me two paintings. One is a large maroon-and-indigo Hevajra mandala, on which he had been working on and off for 23 years. Lok expects to complete the intricate and magnificently detailed representation of the Tantric cosmic universe in 2020. The other, a representation of the elephant-headed Hindu deity Ganesh, but also worshipped by some Tibetan Buddhist schools, has taken him 12 years (he plans to finish it this year). Both works are sure to be hailed as masterpieces by critics and connoisseurs.

Sitting in his office, Lok laments the relative lack of support for Paubha. Not surprisingly, he believes that Nepali art as a field of study has been marginalized somewhat, often taken for being (or represented as) either Indian or Chinese, although there is more overall awareness now, but art thrives on institutional support.

As for the reason that Buddhist art took off in Tibet in such a big way, historians often point to the Tibetan king Songtsen Gampo (c. 605–650), who married the Nepalese princess Bhrikuti Devi. Bhrikuti brought many Nepali artists and craftsmen to Tibet, and, along with the king’s Chinese wife, Princess Wencheng, was instrumental in propagating Buddhism in the country. It is a memorable story—as timeless as it is heartwarming—of two princesses sparking a spiritual and cultural renaissance on the Roof of the World under the patronage of a mighty but benevolent Buddhist emperor.

The Tibet-Nepal bond continued to strengthen, and many Newari artists and craftsmen moved upwards. The most famous among them is Araniko (1245–1306), who traveled to Tibet in the 13th century at the invitation of one of the founders of the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism, Drogon Chogyal Phagpa (1235–80). Araniko later ended up in China (he would not return), working for the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan. A statue commemorates Araniko in present-day Beijing, and he has a highway named after him in Nepal. Indeed, so singular were Araniko’s achievements as an artist that a well-known Nepalese artist has publicly claimed to be his reincarnation.

Tastes in the art world have evolved over the years. The international rise of Tibetan Buddhism, for example, has made thangkas popular products. There is a booming cottage industry across the Kathmandu Valley in which artists produce thangkas in large quantity Lok expressed concern over how thangkas, which are supposed serve a spiritual rather than aesthetic purpose, can be mass-produced, and if they are, whether they can they be called works of art at all.

Then there are also the many creatives who are tapping into the rich reservoir of Buddhist iconography to produce contemporary art—some with avowedly political overtones. Lok believes, on the whole, that they are free to deploy techniques and knowledge from the traditional art. After all, the purpose of art is to open the viewer to new ideas and beliefs—both sacred and mundane. And as long as they follow the ground rules, especially for devotional paintings, he believes there is no harm in having more of them in the world.