In the past 30 years, I have spent a lot of time thinking and teaching about the Shikoku pilgrimage in honor of Kūkai, also known by his posthumous name Kōbō daishi. In January 2015, I wrote an essay for Buddhistdoor Global called “Walking with Kukai–Becoming a Buddha: Pilgrimage in Shingon Buddhism” and, in 2021 an essay on pilgrimages in Japan for a German-language publication.1

In 2000, 2002, 2006, I took students on a three-day bus pilgrimage to Shikoku, during which we visited temples 1–11 (and 12 in 2002), as well as 67–88. In 2016 and 2023, my colleagues and I took students to temples 75 and 66 in the Kagawa Prefecture. During my sabbatical in 2013–14, I rode my bicycle from temple 48 to 64. This year, I decided to visit all 88 temples in four weeks in a hybrid mode, combining hiking with the use of public transportation. I would like to thank BDG for providing a space for me to reflect on my pilgrimage in a short series of essays.

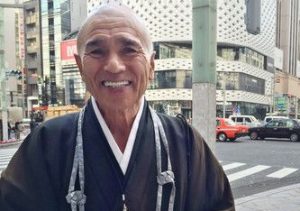

I started my pilgrimage on 8 July of this year and, at the time of writing, I am currently in Kōchi City, where temples 29–32 are located. So far it has been a wonderful but also very trying experience. This year seems to go in the record books for high temperatures in Japan. So it seems that long stretches of open road alternate with steep incline in forest covered hills/mountains. In addition, I am carrying luggage for the time span of four weeks with me. I have had many heartwarming experiences involving, among others, an elderly passerby who donated 200 yen (US$1.43) to my pilgrimage effort, a store owner who opened her beauty salon to me as a refuge from torrential rain and offered me a cup of tea, the friendly staff at temples and accommodations who helped with recommendations and sometimes even bottles of ice-cold water, and fellow pilgrims who helped with advice, a ride, and companionship.

So why do the pilgrimage? In my 2015 article, I provided a philosophical interpretation of the Shikoku pilgrimage, suggesting that it is designed to enable laypeople to practice the “three mysteries” (Jp: sanmitsu), purifying body, speech, and mind, in order to “become a buddha in this very body” (Jp: sokushinjōbutsu). It goes without saying that I still think that this interpretation provides a solid understanding of the role that the pilgrimage plays in Shingon theory and practice. However, most practitioners I have met so far, regardless of whether they walk or drive, commit to the whole pilgrimage or complete only a part, seem not too cognizant of Shingon doctrine. Some even told me they are “non-religious” (Jp: mushūkyō).2

As scholarship, especially that of George Tanabe and Ian Reader, has aptly demonstrated, most practitioners conduct the pilgrimage as a cultural practice, to reflect on a significant rupture in their life, such as retirement, or because they are “practically religious.”3 What scholars call “religious practice” is often seen in the service of “this worldly benefit” (Jp: genze riyaku), such as praying for traffic safety and health, but also to commemorate those who passed on before us. Many of the temples on the route, allegedly all associated with Kūkai, enshrine statues of Kannon Bodhisattva and Jizō Bodhisattva, both seen as protectors of us human beings. Jizō Bodhisattva is especially associated with children, the dead, and the mizuko kuyō ritual, a funerary rite to comfort stillborn children and aborted fetuses.4

I have written of these aspects of Japanese religion and the pilgrimage before. What I am interested in today is the understanding of the pilgrimage and religion in general as a “self-cultivation practice” (Jp: shugyō). While close to the word used in Japanese as a translation for “religion” “shūkyō,” shugyō seems more apt to describe what the pilgrimage and, in my mind, religion in Japan is about: self-cultivation, especially the repetition of the same “form” (Jp: kata). During the pilgrimage this is obviously the repetition of walking. The same, however, applies to the repetition of driving, leaving the car, performing the ritual, returning to the car. At every temple we complete a specific ritual: bowing at the “mountain gate” (Jp: sanmon); washing one’s hand and mouth at the purification basin (Jp: temizuya); ringing the bell—although some temples have stopped this practice; burning incense and candles at the “main hall” (Jp: hondō) and the hall where Kūkai is enshrined (Jp: daishidō); bowing, chanting the Heart Sūtra, and reciting the mantras dedicated to the buddhas and bodhisattvas enshrined in both halls; a visit to the temple office (Jp: nōkyōsho) to receive the stamp and the fuda, a paper token, of the temple; and, finally, another bow at the “mountain gate” as we leave the temple.

What underlines this understanding of the pilgrimage as self-cultivation is the fourfold partition of the pilgrimage. Shikoku, literally, “four kingdoms,” is divided into four prefectures. Roughly a fourth of the pilgrimage is in each prefecture. The Shingon school of Buddhism has assigned each of these four prefectures a spiritual, soteriological, meaning.

Tokushima Prefecture (temples 1–23) is called “the dōjō to arouse the mind” (Jp: hosshin no dōjō);

Kōchi Prefecture (temples 24–39), “the dōjō of self-cultivation” (Jp: shugyō no dōjō);

Ehime Prefecture (temples 40–65), the “dōjō of wisdom and enlightenment” (Jp: bodai no dōjō); and

Kagawa Prefecture (temples 66–88), “the dōjō of nirvāṇa” (Jp: nehan no dōjō).

Most people in the anglophone world are familiar with the term “dōjō.” It is often used to identify buildings/halls where martial arts are practiced. Literally, it means “the place of the Dao/Way.” In the context of the Buddhist canon, however, the term “dōjō” signifies the “place of enlightenment.”5 It designates a place dedicated to self-cultivation practice. The use of the term here implies that, in some sense, the pilgrimage constitutes a geographical representation of the four stages of self-cultivation practice: 1) arousing the mind; 2) self-cultivation proper; 3) enlightenment; and 4) nirvāṇa.

The first 23 temples and around 220 kilometers of the pilgrimage route in Tokushima Prefecture are designed to form the aspiration and motivation for an extremely arduous practice such as the pilgrimage, especially when walked in the summer at a time when places around the world are vying for the heat record. But, of course, the practice of self-cultivation does not start in Kōchi Prefecture but is required on the streets of Tokushima as well as in the mountains around temples 12, 13, 20, and 21. Reaching those temples in a state of complete exhaustion, then, provides a taste of the enlightenment and nirvāṇa symbolized by the temples and the pilgrimage path of Ehime and Kagawa Prefectures. And thus begins the practice of nirvāṇa.

1 “Wallfahrten, buddhistisch: Japanische Pilgerorte/wege/fahrten,” in Das Wissenschaftlich- Religionspädagogische Lexikon im Internet, Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft (2021).

2 For a quick discussion of this phenomenon see my essays for BDG: Japanese Buddhism 101: The Search for the Buddha and “The Mind is the Buddha” – Being Religious (in Japan)

3 Tanabe, George and Ian Reader. 1998. Practically Religious: Worldly Benefits and the Common Religion of Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

4 See my BDG features Buddhist Death Rituals: For the Living – Not for the Dead and The Variety of Practice in Soto Zen Buddhism

5 I would like thank the providers of the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (http://www.acmuller.net) for their translations of Buddhist technical terms.

Related features from BDG

Pilgrimage: Hongluosi, Home to Priceless Artifacts and Heartwarming Legends

In the Footsteps of the Buddha: Ven. Pomnyun Sunim Leads 1,250 Jungto Practitioners on a Pilgrimage to India

From Alena to Yushu, Part 1: How I Found My Way to Shugendo

Journey to the Buddha’s Homeland: Rediscovering Pilgrimage Sites in Nepal

Women in Shugendo: Supporters, Leaders, or Both? Part 1

Pilgrimage: Visiting the Buddhist Mountain of Wutaishan

Pilgrimage: Mount Jiuhua, Kshitigarbha’s Geopark

Journeying Across Shikoku: The Shikoku Pilgrimage