In March 2017, Buddhistdoor Global interviewed Professor Luo Wenhua, a research fellow at the Palace Museum in Beijing and director of the Research Center for Tibetan Buddhist Heritage.* In the interview, Prof. Luo introduced their project of digitizing artifacts and wall paintings in Tibetan Buddhist regions of China, which started in 2013. In August 2017, just a few months after the interview, Prof. Luo and his team made an important discovery at Badha Monastery (嘛达寺) (32°52.256N, 097°23.462E) in Serxu County, Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, in China’s Sichuan Province. In a small hall attached to the tulku’s residence (gungbar labrang), which had been closed off and forgotten after the Cultural Revolution, Prof. Luo and his team uncovered various wall paintings and clay sculptures. Owing to their relatively good condition and unique artistic style, these artifacts are considered rare examples of Tibetan Buddhist art. This article is intended as the first English-language report on the discovery.

Badha Monastery is situated on the east bank of the Jinsha River, a major tributary of the Yangtze River, 3,569 meters above sea level. It was first established in 1269 by the Sakya school, and then transformed into a Gelug monastery in 1440. Serxu County is strategically located on the ancient Tang-Tubo Road** and the Silk Road. To the west, it borders Yulshul County and Chindo County in Yulshul Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. To the north, it adjoins Madoi County in Golog Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. To the east, it meets Darlag County in the same prefecture. Southwest of Badha Monastery there lies the city of Qamdo in Tibet. Today, three tulku lineage systems have been preserved in Badha Monastery, namely Gungbar Che Tshang Rinpoche (大贡巴), Gungbar Chung Tshang Rinpoche (小贡巴), and Gagla Rinpoche (嘎拉). About 140 monks reside in the monastery.

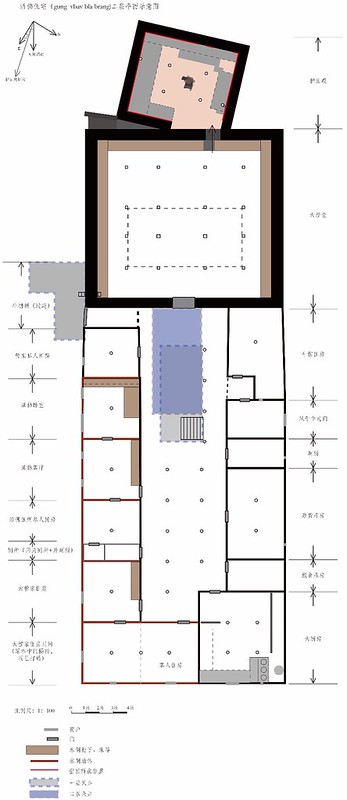

Constructed about 100 years ago, the tulku’s residence (gungbar labrang) is positioned across from the main Scripture Hall of Badha Monastery. The residence complex is composed of three floors—the ground floor is for raising cattle and for storing firewood and other items. The second floor comprises the living quarters for the tulku and his attendants as well as a scripture hall. The second floor also connects with what the monks currently living in the monastery refer to as the “Dharmapala Hall,” where the wall paintings and sculptures were discovered. The third floor of the residence serves as a terrace.

courtesy of Prof. Luo Wenhua

The Dharmapala Hall occupies an area of 40.11 square meters, with an average ceiling height of 2.5 meters. The poor condition and existing repairs of the architectural structure testify to the fact that the hall was constructed much earlier than the tulku’s residence. As shown in the floor plan above, the Scripture Hall was built against the walls of the Dharmapala Hall. For convenience, we shall refer to the easternmost wall of the Dharmapala Hall, which is in adjunct to the Scripture Hall, as wall I, and other walls respectively as II, III, and IV in clockwise order. The wooden panel decors of the Scripture Hall blocked the pathway to the Dharmapala Hall, and therefore the latter escaped the attention of several archaeological surveys in recent decades. On this mission, Prof. Luo and his team entered through a trapdoor. The wall paintings and sculptures inside were damaged during the Cultural Revolution, but have since remained untouched.

Within the Dharmapala Hall are altars made of rammed earth on each side of the four walls. The lower altars on walls I and IV were found to contain sculptures of Yellow Jambhala, Shri Devi, Yama, and fragments of Mahakala. These two altars were possibly used for worshipping the Dharmapalas who guarded the hall. The altars on walls II and III are higher, presenting figures of a higher religious status. It is most likely that altar II was used for yidam worship, judging from the well-preserved sculpture of Yamantaka there. On the narrower altar III is a badly damaged sculpture of a master.

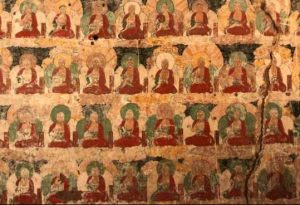

The sections above the altars on all four walls were originally painted, however, few traces of the murals on wall I remain due to later construction of the residence complex. The paintings on walls III and IV have been damaged by rain water that leaked into the structure. Fortunately, most of the wall paintings have survived and cover an area of 31 square meters. Judging from the iconography, wall III is likely to be the central wall: Vajradhara is depicted in the middle, flanked on the right by Atisha (982–1054), an eminent master who reformed Tibetan Buddhism, and on the left by Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), founder of the Gelug school. This indicates that the Dharmapala Hall was probably created after 1440 when the Gelug school took over the monastery. Wall II features the five Tathagathas of Vajradhatu. Wall IV shows two Buddhas, one in the Dharmachakra mudra, and the other in Dhyana and Vitarka mudras, but their identities are unclear. Sadbhuja-Mahakala (Mahakala with six arms) can be recognized on wall I, and this wall may have depicted Dharmapalas, as consistent with the subject matter of the sculptures found there. Prof. Luo has pointed out that the name of the Dharmapala Hall is perhaps based on a misunderstanding by the monks currently living in the monastery; in addition to the wrathful deities, the sculptures and paintings of masters and buddhas seem to suggest that this hall was intended as a small-scale chapel for the tulku’s personal worship.

The clay sculptures and murals in the hall display the superb craftsmanship of the time. The sculptures are robust and expressive, and their artistic characteristics resemble those found at Palcho Monastery in Gyantse County, Shigatse Prefecture, Tibet. The wall paintings demonstrate the transitional style of the 15th–16th centuries between the classical period (pre-15th century) to the late period (17th century). The images of buddhas and bodhisattvas are solemn, the background is mainly painted in red, and the overall color scheme is more traditional and less elaborate. However, a closer look at the details and shades of colors reveals more dynamism, especially in the ornaments and lotus pedestals of the deities. We discussed earlier that the hall was likely built after 1440. Based on further analysis of the style and iconography, Prof. Luo narrowed down the dating of the wall paintings and sculptures to between the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

Prof. Luo explained that these relics are significant in three ways: first, it is rare to see both wall paintings and sculptures preserved in one hall in Tibetan Buddhist regions today, especially after the massive destruction wrought in the 1960s and 1970s. Secondly, while the wall paintings reflect later artistic developments as well as the classical style, the sculptures embody the long artistic traditions of ancient U-Tsang, the cultural heartland of the Tibetan people. Such a stylistic juxtaposition provides excellent materials for academic research. Thirdly, the style of the wall paintings at Badha Monastery is unique in the Garze area. Paintings in a similar style have only been found at Kartsog Lhakhang in Chindo County, Yulshul Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, situated on the west bank of the Jinshan River. This connection between Garze and Yulshul represents the unique style of the Jinsha River area, which has not been fully recognized. The discovery of this site will therefore help to enrich our understanding of the history of Tibetan art in U-Tsang.

* A Mission of Preservation: A Conversation with Prof. Luo Wenhua of the Palace Museum (Buddhistdoor Global)

** Tubo was the Chinese name for the Tibetan Empire (618–842).

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Buddhistdoor View: A Devotional Approach to Preserving Buddhism’s Treasures

Tracing Artistic Developments from India to China: An Introduction to Zhou Mingqun’s Collection of Buddhist Art

Invisible Twice: A Lost Dance Mural