As I sit down to write, I note the churned-up state of my own heart/mind. I am a citizen of the United States of America and we are living through extremely turbulent times in the political and social landscape. It seems like almost everything we’ve considered relatively stable about this country is being shaken up in deeply disturbing ways—and I need to acknowledge that I come from the perspective of a white, middle-class person, so I’ve had privilege in ways that other groups have not, and they might see this much differently.

I am writing this article just a day after our former president survived an attempted assassination. The US presidential debate at the end of June revealed one candidate who lies about almost everything, and another—the current occupant of the office—who seems to be experiencing significant cognitive and physical challenges. The US Supreme Court recently ruled that presidents have immunity from criminal prosecution for official acts during their tenure in office, thus going against two centuries of precedent and overturning a core concept in the founding of the country: that the president is not a king and is not above the law.

All things are impermanent, right? As a Dharma practitioner, this should be one of the things I can roll with and practice with. Yet it still feels fundamentally unsettling. Is it possible that we are living through the dissolution of the US as we know it? Maybe. Is that a bad thing? Maybe not.

I was very moved by a recent piece of writing from Roshi Joan Halifax in which she remembered the generosity and vision of her teacher, Roshi Bernie Glassman, and his emphasis on sitting with “not knowing.” Halifax writes:

Realizing the Bodhisattva Ideal is about being authentic, real, raw, wide open, free of views, intimate, and willing to be broken apart and to repair oneself and each other. Most importantly it is about having the imagination to see things as not necessarily perfect but as complete, as whole, and to imagine a repaired, a healed, and inclusive self; and a world of possibilities, based on the natural richness that arises from resting in radical openness, along with the courage to penetrate the truth of suffering, see it, not flee it, and imagine what liberation can be like for all who suffer.

(Upaya)

Roshi’s words remind us that one of the foundations of the Dharma is the capacity to look at the truth of impermanence and not to turn away. “Radical openness” may make us uncomfortable, but the more we practice it the more we can settle into it, and the more we allow space for new possibilities to emerge. It seems to me that this radical openness is being called on right now as a counterpoint to the hotly reactive certainty that is gripping so many and is stoking flames of hatred and violence.

From that place of radical openness, I want to explore some alternatives that we might be able to imagine beyond the nation-state structure that has been imposed for so long. In particular, we’ll look at some of the parallels between anarchism and Buddhism. Anarchism may carry frightening connotations of chaos and people dressed in black throwing Molotov cocktails, but in actuality it’s a well-considered approach to organizing social and political structures that allows for many possibilities.

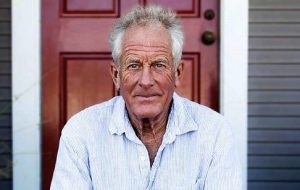

My own introduction to anarchism came from Robert Aitken Roshi, the beloved Zen teacher who was one of the co-founders of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship (BPF). From 2004–07, I served as the BPF’s executive director. Several times I received messages from a student of Aitken Roshi, who was on the BPF’s board of directors, that the Zen master wanted to talk with me about the focus of the organization, apparently feeling it had lost its connection with its original intention.

This, as you might guess, felt pretty intimidating! I had never met Aitken Roshi but I had heard about his fierce intelligence and absolute commitment to social justice. When we finally had a chance to speak on the phone, I was in Washington, DC, in the midst of a march to stop the war in Iraq. I told Roshi that a number of members of our Buddhist Peace Delegation had been arrested for civil disobedience. He expressed appreciation for that and encouraged us to keep it up.

A few months later, a package from Aitken Roshi arrived in the mail. He had sent me a book that he thought I ought to read and that should be put in the BPF office library: Death in the Haymarket (Pantheon Books 2006) by James Green, the story of a small group of organizers and anarchists in Chicago whose actions helped give rise to the first significant labor movement in this country.

In 2006, we invited Aitken Roshi to deliver a speech for a BPF membership gathering at the Garrison Institute. He was no longer able to travel from his home in Hawaii to New York, so the talk was delivered over a telephone and a speaker into the large hallway where we met. Roshi’s talk leaned heavily into educating us about the similarities between anarchism and Buddhism, including this memorable quote:

Buddhism is anarchism, after all, for anarchism is love, trust, selflessness, and all those good Buddhist virtues, including a total lack of imposition on another.

(The Zen Site)

All of this piqued my curiosity. I can’t say I’m an expert by any means, but in the ensuing years I’ve learned a few things:

• In its essence, anarchism is about trusting our capacity to work in voluntary cooperation and to make decisions in ways that do not rely on hierarchy, coercion, and punishment. The word comes from the Greek an-archia: without a ruler.

• Mutual aid is a big part of anarchism. We show up for each other when there is a need, we offer the resources we have. We don’t need to construct large government entities or even nonprofit organizations to replace the relationship-based support that is the glue that holds us together. In other words: interdependence.

• Anarchism does not equal chaos and violence; certainly no more than can arise in other forms of social organization. Consider the violence expressed and sanctioned by national governments in the forms of incarceration and militarization.

As I’ve been watching the trajectory of the US over the last couple of decades, it seems to me that this country is moving toward a division that may not be healed in the current form. Things are falling apart—the center cannot hold, as Yeats once wrote. So perhaps our task is to learn how to consciously let go of the center and practice more equitable and smaller scale forms of social structure such as anarchism. I also think of E. F. Schumacher’s body of work and his declaration that “small is beautiful.”

There are actually examples and variations of this all around, if you look carefully: 12-step recovery groups, Quaker communities, the Occupy Wall Street movement, cooperative groceries stores, and other businesses. Even some of our sanghas function in a more horizontal dimension without “authorities.”

Leadership is not antithetical to anarchism but is perhaps understood differently. There is still a need for people to take responsibility for their own decisions and to support others to do so as well. In a 1993 interview with Barbara Gates, Aitken Roshi said:

I think that the revolutionary Buddhist is an anarchist in the true sense of anarchism, that is to say the person who takes individual responsibility and lives the life of the Dharma as best she or he can within and beside the system. To do this, the individual must gather with like-minded friends.

(Inquiring Mind)

Maybe I’m writing this to reassure myself that while we will live through more frightening scenarios in the weeks and months to come, perhaps we don’t have to be frozen in fear. Can we lean into “not knowing,” as Bernie Glassman encouraged us to do? Can we explore possibilities that are embedded within the falling apart? Perhaps we can practice with forms of relating to each other that don’t rely on domination. Perhaps natural resources can be honored and shared, not commodified and controlled. Perhaps the things we most fear are also the things that will open up doors to ways of being that will sustain us and the Earth.

I don’t know. But I would like to practice radical openness, and I need your help to do so. We all need each other’s help.

See more

Diamond Sangha (Neti Parekh)

The Bodhisattva Ideal: Five Rare Powers (Upaya)

Taking Responsibility (The Zen Site)

Buddhist as Revolutionary: A Conversation with Robert Aitken (Inquiring Mind)

Buddhist Anarchism (The Anarchist Library)

David Graeber on Acting Like an Anarchist (David Graeber)

T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism (The Anarchist Library)

Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (The Anarchist Library)

Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto (Verso Books)

Lovely read! I’m not a US citizen but with the geopolitical knowledge I’ve gained overtime, it’s likely that the centre will no longer hold. There will be alot of uncertainty about global order when the US being the “leader of the modern world” loses it’s own stability.

Thanks for taking time to read and comment, Spiritual Entertainer, appreciate it.