Zeami Motokiyo (c.1363–c.1443) was a master playwright and performer of Noh drama. He was an important figure of the Muromachi period (c.1336–1573), not only as an aesthetician but also for his insights into Buddhist soteriology and the popular culture of the time. In this article, I will introduce Zeami’s Noh plays containing Pure Land Buddhist themes. Of the five major categories, I will focus on Shura (asura), which features ghosts of warriors that continue their battles beyond death, unable to attain liberation.

From pinterest.com

Of the nine extant Shura plays, three feature Pure Land Buddhist themes, all of which were authored by Zeami. The three Pure Land plays are Atsumori, Kiyotsune, and Sanemori, all composed about warriors killed during the Genpei War (1180–85).

Atsumori

Taira no Atsumori (1169–84) was a young general slain by a warrior named Kumagae Naozane. Kumagae was reluctant to kill Atsumori after defeating him in a duel as he discovered the general was no older than his own son. However, Kumagae had to kill him, otherwise another soldier would have taken the trophy. After the event, Kumagae resolved to become a Buddhist monk and pray for Atsumori’s salvation.

The Noh play Atsumori begins with Rensei—Kumagae’s Buddhist name—visiting the area where Atsumori died. At night he begins to perform a memorial for the salvation of Atsumori’s soul. Atsumori’s ghost then appears on the stage, apparently still unable to attain liberation and intent on “clearing away his karma.” Rensei is surprised, as “one invocation of Amida Buddha is supposed to clear away all karma.” Atsumori draws his sword, initially intending to strike Rensei, but decides to accept the prayer upon acknowledging Rensei’s sincerity and persistence. As Atsumori expresses gratitude for his salvation by his former enemy, Rensei does as well, since his own salvation is dependent on Atsumori’s. With that, they become Dharma friends and are promised to be reborn on the same lotus flower.

Kiyotsune

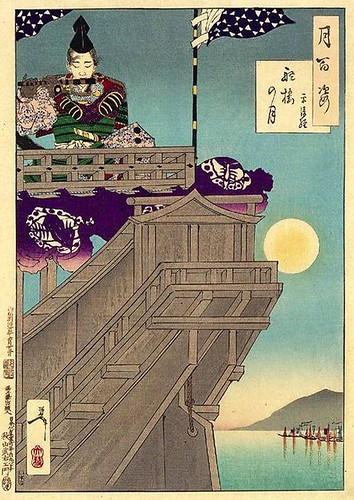

Taira no Kiyotsune (1163–83) died before entering the battlefield. As his clan was driven out of the capital and forced to flee to neighboring islands, Kiyotsune lost hope and promptly drowned himself after reading some scriptures and invoking Amida Buddha.

The Noh play Kiyotsune features his widow, who resents Kiyotsune’s quick decision to end his life after he promised to try his best to make it home alive. When the widow refuses to accept Kiyotsune’s keepsake, his ghost comes to her, resentful about the rejection. He explains to his wife that he would have died sooner or later, so his early death was not to break a promise he could otherwise have kept. Having come to terms with his wife, Kiyotsune attains Buddhahood by the efficacy of his final invocation before death.

Woodblock print by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (1839–92).

From pinterest.com

Sanemori

Saito Sanemori (1111–83) was an aged and experienced warrior who dyed his white hair black before his last battle so that he would not be underestimated. He also did not declare his name as he dueled his opponent lest his age be revealed; and after he was slain, he was not identified until his hair was washed during examination.

The Noh play Sanemori begins with Ta-ami, the successor to the founder of the Ji-shu sect of Pure Land Buddhism, meeting a strange old man who seems to be invisible to others in town. The old man is Sanemori. As he approaches Ta-ami he claims to hear heavenly flutes and see purple clouds, the vehicles of Buddhas, and expresses gratitude as meeting Ta-ami is equivalent to Amida Buddha escorting him to the Pure Land. At night, Ta-ami performs a special ceremony for Sanemori, who reappears in his armor, again expressing gratitude that whoever persistently invokes Amida Buddha is guaranteed rebirth in the Pure Land. Ta-ami explains how enlightenment is infinitely more precious than shiny armor and the Pure Land infinitely more blissful than any field of war, but the play ends on an ambiguous note, with no statement about Sanemori’s salvation. He reenacts his last duel and disappears, imploring Ta-ami to continue praying for him.

Sanemori’s situation is straightforward. As Ta-ami teaches, one needs to actually want to be reborn in the Pure Land wholeheartedly, without remaining attachments to the mundane world, in order for the invocation to take effect. In other words, one needs to adopt the mind of merit-transference and aspiration, one of the three minds taught in the Contemplation Sutra, along with the mind of utmost sincerity and the mind of deep faith. Sanemori needs to want rebirth in the Pure Land more than continued existence in the Shura realm. With Kiyotsune, too, the efficacy of his invocation is delayed due to his remaining attachment to his wife and anticipation that she would not accept the keepsake. Kiyotsune rids himself of attachment by resolving the issue with his wife. Is Atsumori also about overcoming attachments to allow the efficacy of invocation to take effect?

Contemporary scholar Toru Sagara interprets the story as being about Atsumori’s “self-salvation” through overcoming his animosity toward Rensei, which makes the soteriology similar to Sanemori and Kiyotsune. While his acceptance of Rensei through forgoing animosity is important, I think the story is more complex: on the one hand, it is as much about Rensei as about Atsumori. Unlike the other two protagonists, Atsumori does not pray or express a desire to be liberated; he lets go of his animosity when he realizes Rensei’s sincerity. On the other hand, the story is not just about the salvation of Atsumori—it is about Rensei’s salvation. Indeed, there is a sense in which Atsumori is saving Rensei by allowing himself to be saved. From these observations, perhaps Zeami is offering a unique Pure Land Buddhist soteriology, that is, the idea of collaborative liberation in which multiple sentient beings—alive or dead, friends or enemies—help each other attain joint rebirth in the Pure Land.

It is a subject of further study to assess possible sources for the idea of collaborative liberation. It might be a teaching of some wandering priests at the time; it might reflect a popular belief during the early Muromachi period; or it might be Zeami’s own vision of Pure Land Buddhist soteriology. In any case, I think there are many Buddhist insights we can gain from Noh, and I hope that readers of this article will take an interest in exploring the Buddhist themes in Noh dramas.

References

Koyama, Hiroshi, and Kenichiro Sato, editors. Shinpen Nihon Koten Bungaku Zenshu, vol. 58. Tokyo: Shugakukan, first edition 1997, seventh edition 2017.

Sagara, Toru. 1990. Zeami no Uchu. Tokyo: Pelican Sha.

Oyler, Elizabeth, and Michael Watson, eds. 2013. Like Clouds or Mists: Studies and Translations of No Plays of the Genpei War. New York: Cornell University East Asia Program.

Shirane, Haruo, editor. Burton Watson, translator. 2006. The Tales of the Heike. New York: Columbia University Press.

See more