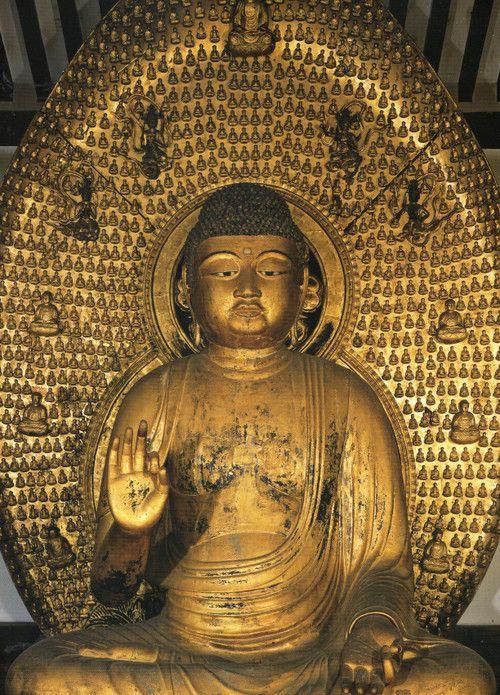

In the main hall of an elegant Pure Land Buddhist temple called Joruri-ji near the city of Nara in Kyoto Prefecture, Japan, a row of nine gilded wood figures of the Buddha Amida (Skt. Amitabha) have sat serenely for almost 1,000 years. They promise devotees rebirth in Amida’s glorious paradise at one of nine levels depending on their accumulated karma, degree of faith, and stage of spiritual practice. The central Amida figure is slightly larger than the four that flank it on each side, and has been imbued with considerable power because of what was placed inside it shortly after its construction. Just over 100 years ago during the Meiji period (1868–1912), a small door in the back of the statue was opened and bundles of sheets of paper, each printed with 100 images of seated Buddhas, were discovered inside. If the images were printed in the early 12th century as believed, the Buddhas are Japan’s earliest surviving printed images and offer fascinating clues about the connection between the Buddhist faith and the evolution of printed imagery.

Woodblock printing was invented in China around 600 CE and was probably introduced to Japan sometime in the 7th century, when it was used to mass-produce sacred Buddhist texts, or sutras. Japan’s earliest surviving printed Buddhist texts are the small printed charms, or darani (Skt. dharani), that were commissioned by the Japanese empress Shotoku between the years 764 and 770. In 764, the empress ordered one million small wood pagodas (J. hyakumanto) to be made and filled with these printed charms in gratitude for the suppression of a rebellion against her court and for future protection of the realm by the Buddha. Most of the pagodas were sent to Buddhist temples around the country, but she kept 100,000 in the ten main temples in the capital (then Nara) as protection. Apart from a few examples in museums and private collections, only the temple Horyu-ji near Nara still possesses evidence of this massive printing project.

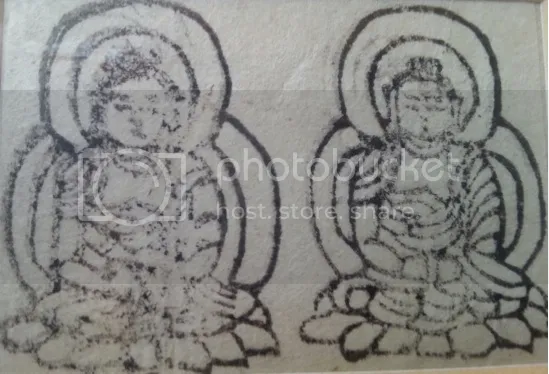

The first Japanese printed Buddhist images were probably made around the 8th century from Chinese blocks brought back by Japanese Buddhist priests who had visited China. The earliest of these images to survive, dating from the Heian (794–1185) to Muromachi (1392–1573) periods, share similar characteristics. Most are small, being an inch or so in height, and are simply rendered, often in thick uneven lines and with abbreviated iconographic details. They can be divided into two types according to technique: inbutsu (stamped Buddhas) and shubutsu (rubbed Buddhas). The term inbutsu generally refers to small images of a single deity carved onto a small block which is inked and then pressed onto paper, like the seals which are still used today. In some cases, these images of Buddhas and other deities were stamped alongside handwritten Buddhist sutras, no doubt to lend spiritual power to the prayers.

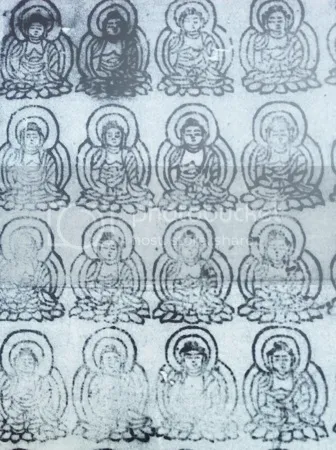

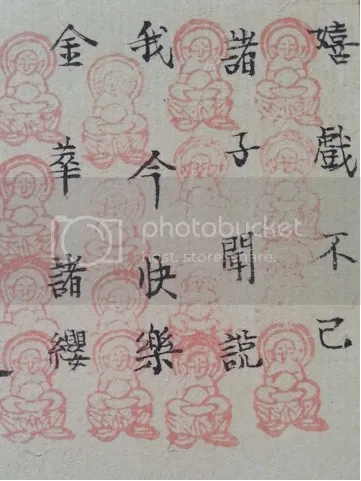

In contrast, shubutsu are usually made using larger blocks which are carved with one or several figures. The block is placed face up, and paper is placed on the inked surface and rubbed with a circular pad called a baren. This is the typical technique used in East Asian woodblock printing, and was developed to great sophistication in Japan’s ukiyo-e prints of the 17th–19th century. This is also the technique that was used to create the sheets of printed Buddha images that were extracted from the Amida statue at Joruri-ji.

The Joruri-ji sheets were printed with ten rows of ten seated Buddha figures, most likely Amida. The wood blocks were usually carved by priests and used by priests or lay Buddhist devotees to print images of Buddhas, bodhisattvas, or other deities onto paper as a Buddhist ritual activity. Traditionally, the creation of an image of a particular Buddhist deity, whether a sculpture, painting, or print, has been a way of acquiring religious merit. Printing an image of a deity was the simplest way of creating a Buddha, and many devotees, usually members of the Buddhist clergy or nobility in the early period, produced such images daily as a type of printed prayer to a deity for improved health, the repose of a deceased loved one, or rebirth in paradise.

Repetition has always been an important element of Buddhist practice, and the more images a devotee creates, the more merit he or she accrues. The repetition of the image serves as the visual equivalent of chanting the name of a deity over and over again, a means not only of focusing the mind but also of evoking the deity’s blessing, accruing good karma, and strengthening one’s bond with the deity. The printing of images of the Buddha 100 times on one sheet of paper is a device rooted in Chinese Buddhist art, and papers found stamped with hundreds of small Buddha images have been found in the early Buddhist cave temples of Dunhuang in northwest China. In the case of these Japanese sheets of Buddhas, the initial carving of 100 Buddhas on a single block by a Buddhist priest was painstaking, but once completed it provided the worshipper with a short-cut method of printing many images at once and thus acquiring more religious merit. Each little printed Buddha has an unsophisticated charm, and the repetition of similar rounded images creates a gentle rhythm as well as a strong sense of the infinite, suggesting the Buddha’s limitless power.

Unlike many images of the Buddha that have been created over the centuries, these early printed images were not meant to be viewed by others or used in worship rituals. In the case of the Joruri-ji printed Buddhas, it is believed that the printed sheets were placed inside the statue not only for safekeeping, but also to further strengthen the bond between the devotee and the deity, accrue positive karma, and receive the deity’s blessing. Furthermore, the action increased the spiritual power of the statue by contributing to it the power of each of the hundreds of smaller printed images. The simplicity of these tiny Buddhas printed with rough outlines and without color is deceptive. The process of carving the figures into a woodblock, printing them on paper, and then placing them inside a sacred statue served as a multi-staged act of art, devotion, and spiritual empowerment that bonded priest, devotee, and deity in a way rarely seen elsewhere in the Buddhist world.

Meher McArthur is an Asian art curator, writer, and educator based in Los Angeles. She has curated over 20 exhibitions on aspects of Asian art. Her publications include Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs and Symbols (Thames & Hudson, 2002), The Arts of Asia: Materials, Techniques, Styles (Thames & Hudson, 2005), and Confucius: A Biography (Quercus, London, 2010; Pegasus Books, New York, 2011).