Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha, resides as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in present-day Nepal. However, with the effects of mass tourism this sacred pilgrimage destination is quickly becoming less a sacred garden and more a concrete Disneyland.

When I visited, I was struck by the juxtaposition of ornate monasteries with expanses of construction between them that made rickshaw or bike transportation almost a necessity. The 4.8- by 1.6-kilometer area is split into Theravada monasteries in the east and Mahayana and Vajrayana monasteries in the west, each of which are paid for and maintained by a different country. Tours on loud motorboats are operated on a brick-lined canal spanned by arched bridges, panning dramatically between the two main monuments: the Eternal Peace Flame and the Peace Pagoda.

The rising influx of visitors and the rush for development, however, has put significant strain on the habitats of local wildlife, especially the Sarus crane, the tallest flying bird in the world and part of Lumbini’s ecological diversity.

As told by Dharmendra Pal, program coordinator for the Lumbini Crane Sanctuary, the Sarus crane is intertwined with the story of the Buddha. The young Siddhartha Gautama and his cousin Devadatta were exploring the gardens behind the palace when a large, low-flying crane caught their attention. Devadatta took out an arrow and shot the bird. The injured animal then took refuge by the young Buddha-to-be, who calmed the bird by removing the arrow and tending to the wound.

The cousins fought over who could claim the bird. Devadatta argued that because he shot it and had the right to hunt, it belonged to him. Siddhartha said that because the bird had not yet died and was seeking protection, it was his right to take care of it.

They went to Siddhartha’s father, the king, who took the moral issue to the court. After a three-hour discussion, the court came to the conclusion: “The right to life belongs to those who want to preserve it, not to those who want to destroy it. That is the very definition of life. Only when you preserve it you have life. Otherwise, when you destroy it, you have no life.”

Prince Siddhartha’s fight to save the Sarus crane continues today. The birds are critically endangered as a result of habitat destruction in Lumbini, pesticides leaching into their food chain, thinner egg shells leading to a lower hatching rate, and electrocution from flying into power transmission lines.

Dharmendra and I stood on a watch tower in the middle of the quiet sanctuary, the early morning sun highlighting the bright red bobbing heads of two cranes and their chick as they weaved between the tall grass. Explaining the importance of the cranes to the local ecosystem, particularly for the local farmers, Dharmendra said, “The cranes are very close to farmers and it’s proven that they eat the insects that destroy crops. It’s a good sign for farmers to have a pair nearby, and they will lay out materials for the cranes to nest.”

Dharmendra told me that Sarus cranes live in pairs and only have one baby annually. Often, however, their eggs are eaten by jackals or stolen by local children to make omelets.

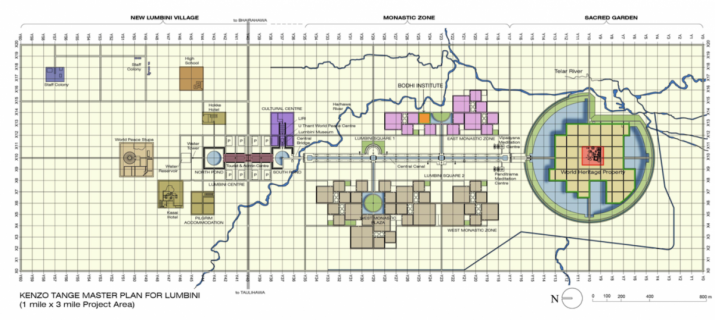

Kenzō Tange, a famous Japanese architect, created the master plan for Lumbini in 1978. He envisioned leaving 60 per cent of the land as nature preserve to reflect the Buddha’s teachings on the harmony between humans and nature. The International Crane Foundation has a 50-year lease with the Lumbini Development Trust (LDT) for a 254-acre bird sanctuary on the northern edge of the Lumbini Master Plan.

Finding a delicate balance between tourist accommodation and nature preservation is a major challenge. In the crane sanctuary, ponds have been built and the natural wetlands preserved to create ideal conditions for cranes to mate, hatch, and raise chicks.

Venerable Metteyya Sakyaputta, a Buddhist monk and scholar, grew up in a small village in the birthplace of the Buddha. He has been directing environmental management and education in the area since he was a young student volunteer at the Lumbini Crane Sanctuary, and has now been appointed vice chairman of the Lumbini Development Trust (LDT).

“When I began to learn about the ecosystem, it was a 180-degree turn for me,” said Ven. Metteyya. “My understanding as a kid was that rivers are so mighty and trees are so mighty, so whatever we do does not affect them. I think we need to realize that tiny actions do affect them. They’re not so mighty anymore. You need that presence. You need that part of what makes the ecosystem. You are very much part of it. It’s such a vulnerable, simple connection.”

Ven. Metteyya aims to create an environmental management plan for Lumbini during his term. Part of this is the launch of a new phase of the crane sanctuary at the end of November as a nature center for visitors.

Unfortunately, the area is also the last open area available for development, and projects are constantly being proposed. Lobbyists are offering big money to build hotels, a huge meditation center, and even a five-star shopping complex. Understanding the importance of preserving this area is crucial for the Lumbini Crane Sanctuary, and the survival of the Sarus crane.

Artist, environmentalist, and Buddhist practitioner Lillian Ball recently released a documentary that tells the story of the crane sanctuary to spread word about the habitat destruction. Sanctuary, which is fiscally sponsored by the Buddhist Film Foundation, is being screened in several cities to raise awareness.

The Buddha’s teaching is compassion. Applied Buddhism puts compassion in action. Ven. Metteyya practices this by showing how Buddhism and conservation can work together to protect the Sarus cranes, and the Earth.

“As Buddhists, we put so much money into concrete buildings. We don’t do any nature conservation,” said Ven. Metteyya, who believes the story of the crane could inspire visitors to learn something from the Buddha, in his birthplace. “Take one hour, walking in nature, have some meditation, spot some birds, and very slyly, educate them about climate change. Bring them to a place and ask, how are you going to contribute to taking care?”

Ven. Metteyya then emphasized the teaching from the Buddha’s story that led him to where his intentions lie today: “The right to life belongs to those who want to preserve it.”

Shaelyn McHugh is pursuing a degree in communications at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She has a passion for the natural world and global community, and enjoys discussing artificial intelligence and food.

References

Crane Sanctuary; Dharmendra Pal; Lumbini, 17 October 2018.

O’Brien, Barbara. 2018. “The Birth of the Buddha: Legend and Myth,” ThoughtCo. 27 March.

Personal History and Lumbini Development Trust; Venerable Metteyya Sakyaputta; Lumbini, 18 October 2018.

See more

LUMBINI CRANE SANCTUARY (Lumbini Social Service Foundation)

Cranes replace cranes in Buddha’s birthplace (Nepali Times)

Buddha Once Save a Crane. Now Its Descendants Are in Danger (Tricycle)