I was listening to my favorite podcast as I drove home from a retreat last month. In a reversal of roles, On Being host Krista Tippett was being interviewed by writer Pico Iyer. The occasion was the publication of Tippett’s new book, Becoming Wise.

A few minutes into the conversation, Tippett said, “Perfection can be a goal, but it’s never a destination.”*

That line resonated with me. It felt like an echo of words I often say to my Tibetan appliqué students, the Stitching Buddhas. And it got me thinking. What is a proper role for perfection in our lives? How do we relate to it—as Buddhists, as artists, as learners?

Many of my students have a perfectionist streak. That’s not surprising among people who are drawn to artwork of such fine detail and intricacy. In a sense, the intricacy of the artwork would not be achievable without a good dose of perfectionism, or at least a strong orientation toward excellence. If one were to approach the craft casually, it wouldn’t be long before the pieces of silk became too distorted to fit together.

hundreds of pieces of silk outlined with horsehair cords

Sometimes, however, a strict commitment to perfection obstructs a student’s progress. She is unwilling to move forward until she’s perfected a particular step. And, stuck in one place, she’s unable to improve. When this happens, I encourage the student to temporarily set her perfectionist ideal aside. Of course, I offer suggestions for improving the technique in question. But, rather than dwelling on that improvement, I encourage the student to move forward while paying attention to what unfolds. Often, refinement toward perfection can only occur by moving imperfectly to the next step.

In letting one imperfect action unfold into the next, we gain an understanding of the interconnected nature of the process as a whole. We directly observe the effects of our actions and see why some actions are preferred over others. Engaging directly, we learn more deeply than we ever can from explanations alone.

As our project takes shape, the perfection of the whole becomes evident, even as it’s built on a series of imperfect steps. Fiber and fabric are irregular, like the world, like our lives. Only a small part of the process is within our control.

Football coach Vince Lombardi said, “Perfection is not attainable, but if we chase perfection we can catch excellence.”** The magic happens in the chasing. And to chase, we have to keep moving, never to arrive at a perfect condition but to open more and more to the perfectness of the whole.

In “Think Like a Black Belt,” author Jim Bouchard writes: “Set a big goal; nothing wrong with that. Now instead of letting the moment of attainment represent your arrival at perfection; let every moment of the process be a moment of perfection. Change perfection from a noun to a verb. As you fully engage in the process of attaining your goals you are, in every moment, fully engaged in the process of perfection. Every step: forward, backwards and sideways is part of this process. I know you’ve got somewhere you want to go; but right now you’re doing what it takes to get there . . . Perfection is not a destination, it’s a never-ending process . . .”***

So what does this have to do with Buddhist practice?

Zen teacher Shunryu Suzuki said, “Nothing we see or hear is perfect. But right there—in the imperfection is perfect reality” (Suzuki 2003, 129). In a realistic pursuit of perfection, and in opening to the perfection of reality as it is, without judgment, one finds and creates beauty, honor, excellence, and reverence.

Mahayana Buddhism urges us to train ourselves in the practice of the Six Perfections (Generosity, Ethics, Patience, Enthusiastic Effort, Concentration, and Wisdom). The term “perfection” in this instance is translated from the Sanskrit word paramita. Translation is never a neutral activity. There’s not a one-to-one relationship between words of various languages. Thus, translation always carries a degree of interpretation. Choices must be made, and these choices impact the way teachings are understood in different places.

So what about this word, paramita? What choices were made in its translation? Scholar Donald S. Lopez, Jr. describes the etymology of the term, in two parts: “The term paramita, commonly translated as ‘perfection,’ has two etymologies. The first derives it from the word parama, meaning ‘highest,’ ‘most distant,’ and hence, ‘chief,’ ‘primary,’ ‘most excellent.’ Hence, the substantive can be rendered ‘excellence’ or ‘perfection.’ This reading is supported by the Madhyantavibhaga (V.4), where the twelve excellences (parama) are associated with the ten perfections (paramita)” (Lopez 1988, 21).

Given the Western psychological landscape, where complex feelings of unworthiness and inadequacy have become intertwined with perfectionism, we might have been better served if early English translators of Buddhism had exhorted us to practice Six Excellences or Six Supreme Qualities rather than Six Perfections.

Lopez continues to examine the term paramita, as follows:

“A more creative yet widely reported etymology divides paramita into para and mita, with para meaning ‘beyond,’ ‘the further bank, shore or boundary,’ and mita, meaning ‘that which has arrived,’ or ita meaning ‘that which goes.’ Paramita, then means ‘that which has gone beyond,’ ‘that which goes beyond,’ or ‘transcendent’ ” (Lopez 1988, 21–22).

Early Tibetan translators chose this second meaning when they translated the Buddha’s teachings from Sanskrit in the 7th century. Thus, the Tibetan word for paramita is pha-rol-tu-phyin-pa, which literally means “gone to the other shore.” And where might we find this “other shore”?

of nature

In a 1999 talk on the Six Paramitas, Pema Chödrön explained that on one level “going to the other shore” implies that we go from our current, messed-up state to a transcendent, kind, wise, compassionate, “perfect” state. But, on a deeper level, the journey to the other shore is one that takes us beyond dualistic, limited thinking. It is a journey from certainty and attachment to openness and freedom, where perfection exists without comparison and with no imperfection against which to posit it. And “getting there” is not the point.

The spiritual path is not a ladder we climb to the next level, leaving behind what’s difficult and unpleasant, explains Chödrön. Rather, it’s a path we explore forever, paying tender attention to the ground that’s always right there under our feet. Far from leaving behind all that’s difficult and unpleasant, we encounter all our suffering and inadequacy along the spiritual path. **** The same is true on the art-making path.

symbolizes the purity of the ground on which Tara steps.

Training in the Paramitas (the so-called Perfections) is training in steadfastness with ourselves, through high and low, agreeable and disagreeable, greeting it all with infinite, loving curiosity. And training in our craft is training in steadfastness with ourselves and with our work—with our mistakes, our inadequate skills, and our impatience, as well as our mastery, our creativity, and the beauty we create. We are called upon to practice perfection, not to be perfect, until perfection is recognized where it’s always been. Chasing perfection, we catch excellence, stitch by stitch and step by step.

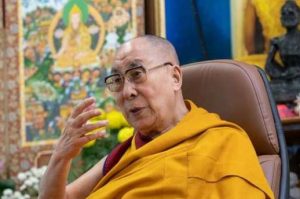

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo is a textile artist, teacher, and caretaker of the sacred Tibetan tradition of silk appliqué thangkas. Trained by two of the finest living masters of this rare art form, she stitches pieces of silk into fabric mosaics that bring the transformative figures of Buddhist meditation to life. Encouraged by His Holiness the Dalai Lama to make this art relevant across religions and cultures, Leslie created the Stitching Buddhas Virtual Apprentice Program to help women around the world integrate their spiritual and creative paths. A selection of her artwork is currently on view at the Fresno Art Museum (Fiber Art Master Works, 20 May–28 August 2016). Leslie is also a member of the Dakini As Art collective. To learn more about Leslie, her work, and Dakini As Art, please visit Dakini As Art.

The film Creating Buddhas: the Making and Meaning of Fabric Thangkas is available on DVD and online at http://threadsofawakening.com/video.

* On Being, The Mystery and Art of Living, 5 May 2016

*** Jim Bouchard, Think Like a Black Belt: Perfection is Not a Destination, It’s a Never-Ending Process

**** Pema Chodron: The Six Paramitas

See more

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, Threads of Awakening (Homepage)

Stitching as Meditation in the Pieced-Silk Thangkas of Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo (Buddhistdoor Global)

Teaching Western Women an Ancient Tibetan Art and Gaining Wisdom Along the Way (Buddhistdoor Global)

Emperors, Lamas, and Silk: the Origin of Fabric Thangkas (Buddhistdoor Global)

References

Lopez, Donald S., Jr. 1988. The Heart Sutra Explained: Indian and Tibetan Commentaries. Albany: SUNY Press.

Suzuki, Shunryu. 2003. Not Always So: Practicing the True Spirit of Zen. Edited by Edward Espe Brown. New York: HarperCollins.

All photos except the last are by the author.