One thing that people don’t discuss when the topic of homesteading comes up is how it changes the way you eat. For the average American, meal plans are decided based on personal preferences. If they are especially frugal, they might temper those preferences based on what’s on sale at the store. Either way, the process is straight-forward—figure out the food budget, make a list of items, and shop.

That changes, however, when one strives to live off the land. Issues like seasonality and crop yield come into play. Sometimes what we want to eat is not the same as what’s available. Case in point, I planted several large beds of potatoes this year because I wasn’t sure how they would do. My thinking was that if I planted as many as possible, even a bad harvest would yield semi-decent results.

To my surprise, I didn’t have a semi-decent harvest. I had an incredible one. And now there are more potatoes sitting in my basement than I can handle. It’s a problem, but an amusing one and the solution is simple. Eat lots of potatoes and then eat some more.

So my partner and I are enjoying hash browns for breakfast each morning, baked potatoes for lunch, and mashed potatoes with dinner each night. I’ll never look at spuds the same way again.

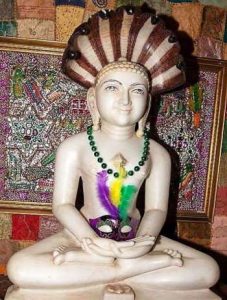

This course of events has caused me to reflect on the spiritual teachings of Vasubandhu, a fourth century Indian Buddhist philosopher. Vasubandhu was a member of the Yogacara school of Indian Mahayana Buddhism, which taught that our experiences come from karmic seeds that are planted in the storehouse consciousness. When conditions are right these seeds ripen and create the mental transformations that form our reality.

So an important part of Yogacara practice is to study the mind and notice when negative karmic seeds—greed, anger, ignorance, and so on—are ripening, so that we can choose to not act on them. Also, practitioners work to plant positive karmic seeds—humility, kindness, generosity, etc.—to benefit themselves and others.

To understand how this works, we can imagine a person scrolling through social media. Perhaps a news story comes up on their feed that they don’t like. Due to past experiences, the karmic seed of disgust may emerge in their mind. They might be tempted to act on these feelings by writing an angry post or sending a mean tweet.

If they succumb to the temptation, the karmic seed of disgust ripens into an action rooted in anger. Their angry tweet results in additional karmic seeds of negativity being planted into the storehouse consciousness and the cycle of suffering continues.

In contrast, if that same person notices disgust rising in their mind and chooses to respond by continuing to scroll down the screen without posting anything, the karmic seed never ripens and the cycle of suffering is ended.

In this way, practitioners cultivate minds of peace and loving-kindness by only acting on thoughts that are positive and life-affirming. Through their actions they plant the seeds of enlightenment in their mind.

When I look at the potatoes from my garden, they demonstrate the power of this practice. I wanted a lot of potatoes, so I planted a lot of potatoes. And the result is that I’m eating them with every meal.

The lesson I take from this is simple and direct: if we want something to grow in our garden, we must be intentional about the seeds we plant.

As I contemplate the teachings of Vasubandhu, I find myself asking questions like, “What is the mind-state I’m trying to grow?” and “Do my actions support that growth?”

With these questions in mind, I tailor my actions less on the thoughts that come into my mind and more on the result that I’m hoping to secure. I don’t engage with content on the internet that causes karmic seeds of fear or anger to ripen in my mind. I strive to use kind, polite speech when I interact with people during the day. And I go about my chores with a mind of gratitude.

These are small actions, but like potatoes, they can grow into a big harvest if they are practiced consistently. In the end, growing a mind of enlightenment is simple. We just need to plant the seeds.

Namu Amida Butsu

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Dharma’s Garden – Nourishing the Local Community through Homesteading

Right Mindfulness and Vegetable Gardens

Teachings from the Vegetable Patch

Green Shoots of Hope – Youth Climate Leaders in Asia and Africa

Buddhistdoor View: Overcoming Our Denial of Responsibility for Climate Change

Great advice!