It all began, according to Jacques Marchais, a child actress turned gallery owner and museum founder, with a childhood love of dolls. Not an uncommon pastime, she made references in her diary to playing with a set of 18 dolls. In actuality, according to museum executive director Meg Ventrudo, the “dolls” were statues of Bon deities, the pre-Buddhist tradition of Tibet that is still revered and practiced to this day. Ventrudo adds that the statues may have came into Marchais’s possession from her great grandfather, a trader from Philadelphia. What is clear is that this childhood pastime would blossom into arguably the most exquisite collection of Buddhist and Himalayan art in museum form in the United States today.

Marchais’s collection is now housed in a museum resembling a Himalayan monastery, the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art, high up on Lighthouse Hill on Staten Island, one of New York City’s lesser-known boroughs. Opened in 1947, the museum now sees more than 5,000 visitors per year.

Yet Marchais was not raised in a Buddhist family, nor did she ever travel outside the US. Marchais was born in the American Midwest in 1887. Abandoned by her father, her mother, in order to support them, engaged her in the profession of child elocution as it was called in those days. Today, we would refer to that as child acting.

Often performing in the homes of wealthy people, at times Marchais would be entered into expensive private schools under the sponsorship of patrons, later to be collected by her mother once the family finances had improved. Perhaps it was this lifestyle that forged the resilience behind her independent spirit that was deeply passionate about art and religion.

“She was just someone who was drawn to Asia, and was fascinated by it and put together this fantastic collection,” Ventrudo offers.

Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art

Today the collection of objects includes a library of vintage books and photographs, also hand chosen by Marchais, containing rich historical details from some of the earliest photographed expeditions to Tibet.

Before opening the museum, Marchais owned an art gallery in Manhattan called the Jacques Marchais Gallery, Art of Tibet, Art of India. Much of the art sold there was Indian, yet she kept the Tibetan pieces for herself, eventually donating them to the museum.

“Her collection is very specific—it’s Tibet, Nepal, northern China, and Mongolia. There are a few Japanese pieces in the collection, there are a few Burmese pieces, but they probably came with a lot of objects and were not things that she specifically sought out. There are maybe one or two Thai pieces, but she was not collecting broad-brush Buddhist stuff; she was very connected to Central Asia.”

The museum itself sits on a plot of land adjacent to the farmhouse she once owned with her entrepreneurial husband, Harry Klauber. Marchais had three children from a previous marriage, who came to live with the couple on Staten Island when they were teenagers. Prior to that they were raised by relatives. Today the house is no longer owned by the museum, but it is immediately visible from the museum grounds.

Why Staten Island? “Apparently Jacques and Harry wanted to live on a farm that was within commuting distance of Manhattan,” says Ventrudo. The museum stands in stark contrast to the three-story Dutch Colonial Farm house. Instead, the museum bears an uncanny resemblance to a Tibetan Buddhist monastery in the Himalaya, something for which Marchais took inspiration strictly from books: “Everything is built into the ground—so we are one level below the street,” Ventrudo explains. The main gallery of the museum, which holds paintings and sacred objects, Marchais had envisioned as a chanting hall: “She decided she wanted to design what she thought a chanting hall would look like, and she got really close to the intention of a Tibetan temple.”

How did she acquire such a magnificent collection? She was buying from art dealers and auction houses at an auspicious time: “The time period of this is significant because she was collecting after the fall of the Chinese dynasties but before China invaded Tibet. So this rare time when a lot of this art came into the Western market is when she was buying it,” Ventrudo recounts.

The main gallery is breathtaking, containing a shrine that Marchais owned personally: “This red and gold shrine is hers—about 90 per cent of the collection is hers and the remaining 10 per cent is what we have acquired since her death or purchased, but primarily through donations.”

Just as arrestingly beautiful is the land on which the museum sits; it is not uncommon to see deer or hawks on the grounds. In the summer, a lotus pond with fish welcomes visitors in an image of peace and serenity.

“This is the remainder of our space and these woods are ours too, but we just keep it green. In the summer this area is totally engulfed in trees and it’s nice and cool back here,” says Ventrudo. “These are trifoliate oranges trees, which are native to Japan, Tibet, and Korea. They are original plantings on this site—an American service member brought them back in 1945 from Japan . . . we have two here and two up there. And we have been putting in plants that are native to the Himalaya, such as rhododendrons and azaleas.”

A patio space crisscrossed with prayer flags hosts several objects, such as a white Burmese Buddha statue: “This is Burmese, but again it’s sort of an odd item for her to have as it’s not Himalayan. It features Bengali lettering that says, ‘Oh wise men of Sakya.’”

Many monks and lamas have performed here, with traditional Buddhist dance and fire pujas among the outdoor programming that takes place. From the patio, one can see the museum building, which was built entirely out of local stone. The pointy copper top is a replica of the top of the temple at Jehol in Chendgu, China.

“I think Jacques tried to create a retreat-like space, before people were going on retreats,” explains Ventrudo. Indeed, the most arresting visual at the museum are remnants of actual meditation cells, which Marchais had intended to be used for Buddhist retreat practice. This vision was never manifested as she died in 1948, six months after the museum opened.

Photo by the author

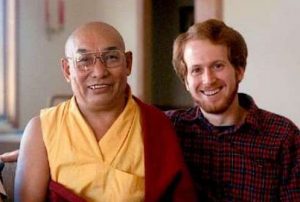

The museum hosts Tibetan cultural events such as Losar celebrations, picnics for the Himalayan Elders Association, weekly meditation on Saturdays, and even film screenings on Sundays. His Holiness the Dalai Lama visited in 1991 and performed a consecration ceremony for the site. In 1973, the His Holiness the 16th Karmapa visited, as have many other teachers in the Tibetan Buddhist and Bon traditions, such as 33 Menri Trizin of the Bon Lineage, The Nechung Oracle, Ven. Thupten Ngodrup, and His Holiness Ngawang Tenzing (now retired), who was the previous Dorje Lopen Rinpoche of Bhutan.

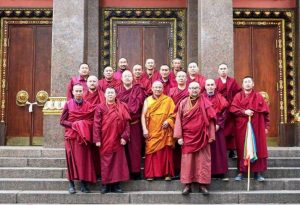

“For us, because we are a museum and we primarily operate as a museum, and not as a Dharma center, it gives us the flexibility to have Sakya monks here, or Kagyu monks here, or Sri Lankan monks. It’s about preserving the Buddhist tradition and demonstrating that to visitors,” says Ventrudo. “We see it as a center where practitioners can participate in a Medicine Buddha puja, but do it with safety of the collection at the same time, so any programs we do are always open to the public.”

Notably there is also a meaningful education component: “For example the monks or lamas will speak Tibetan and there is a translator translating it into English. I personally find this fascinating because they get to hear Tibetan spoken in the space. We have a lot of programs: there are Tibetan folk dances here, and we have had the Sri Lankan dancers from Staten Island perform.”

The museum is also a place for those curious about the art objects, Tibetan culture, and even as a place to be transported by the beauty and peace of an environment so different to its immediate surroundings. The executive director and her staff conduct outreach to Tibetan communities and work with contemporary Tibetan artists. The museum attracts many international visitors who are Buddhists, and local school children, art students, and boy and girl scout troops also come to learn and experience the profound collection of this pioneering and brilliant women who died far too soon.

“Our mission is to preserve the art and culture of Tibet, whether that is through Buddhist art, or contemporary art, music, whatever, so we use this space inside the museum and we use the outside garden,” says Ventrudo.

What’s next for the museum? “We are doing an exhibit of the Maitreyas in the collection. There are some that are in storage that will be coming out to be put on display,” Ventrudo adds. “We have a shrine with a seated Maitreya so that will come out of storage to be on display and we are also doing a small show of objects related to pilgrimages.”

Thanks to a woman with a non-traditional education who only attended school until the eighth grade, an institution was founded unparalleled in its contribution to preserving and educating Himalayan Buddhist art, culture, and scholarship. What a great blessing for the United States!

See more