Anyone unfamiliar with the richness of Buddhist practice in Southeast Asia would do well to visit this unusual exhibition currently on at the British Museum in London. Buddhist art of this region rarely features in special exhibitions in this part of the world. However, the aim of this exhibition was not necessarily to display “art,” but rather aspects of the religion as practiced on a daily basis in Myanmar (Burma) and Thailand. Curator Alexandra Green was also keen to show artifacts from the museum’s collection, many of which have lain in storage un-displayed all these years. They include Thai Buddha images collected during the 19th century by the colonial administrator Sir Stamford Raffles, who is better known for his interests in Indonesia and Malaya.

The Buddha standing with hands in the gesture of reassurance or quelling the fighting relatives, Thailand. 1700s, gilt bronze. Collected by Sir Stamford Raffles and donated by Rev. William Charles Raffles Flint.

This small but highly colorful show amply illustrates the intriguing mix of spiritual practices that infuses the Theravada Buddhist tradition of these countries. Daily practices which help people on their journey include, for example, spirit worship, divination, and numerology in addition to paying homage to the Buddha and meditation. Ultimately, this show questions perceptions of the Theravada tradition. Is it really a strict, puritanical religion as often portrayed in 19th-century Western scholarship? Local Buddhists often make a clear distinction between officially sanctioned religious practices and what actually happens on the ground. However, it is not always so clear-cut which practices simply coexist and which have become integral to what we think of as “Buddhist.” For example, local animistic and other rituals have often been subsumed into Buddhist merit-making rituals, such as the Salak Yom offering-tree ritual in northern Thailand (Denes 2012). And this process of integration may not even have occurred very long ago—the origins of the term “Theravada” have received growing scholarly interest, and are thought to be more recent than one would think (Skilling et al. 2012, xiv–xv). An exhibition like this encourages us to look again.

Arranged by themes, the exhibition comprises a wide range of objects, from 18th-century sculptures to contemporary posters, amulets, and daily items given as ritual offerings. The section on “Biography and Cosmology” illustrates themes that are popular in the art of this region, particularly in manuscripts, temple paintings, and textile traditions such as the Burmese embroideries (kalaga) that became popular during the colonial period. The jataka or stories of the Buddha’s previous lives typically focus on the last of his ten lives.

A group comprising a Thai painting of the Buddha descending from Tavatimsa Heaven flanked by Burmese images of the evil deity Mara and the Hindu deity Sakka (Indra) emphasizes the cross-cultural approach to this show. These unusual sculptural depictions highlight their attributes: a crown for Mara’s royal status and a notebook for Sakka to report on the good and bad deeds of human beings.

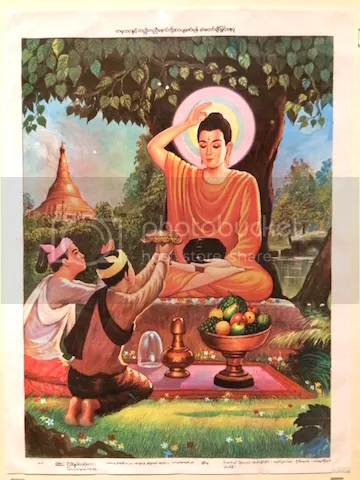

The notion of good karma and making merit in order to progress on the path to enlightenment is vividly portrayed in popular mass-produced posters, such as this one illustrating the legendary history of Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, which is believed to have been built during the time of the Buddha. Pilgrimages to such important places have long been part of the Buddhist tradition in these countries, and these days Thai pilgrims visit the Shwedagon in ever-increasing numbers.

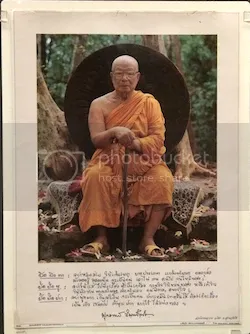

Contemporary materials also illustrate the section on “Powerful Beings.” Here, the merit that is cultivated by notable Thai monks such as Buddhadasa Bhikkhu and Somdet To is shared with devotees who make collections of sacred objects such as photographs, amulets, and even footprints. These are usually blessed by the monk and then used by the devotee for protection against ill health and disasters. There is even a CD of sermons on display, to emphasize that active listening is also a meritorious practice.

And finally, a section on “Power and Protection” takes the amuletic tradition further with a showcase on sacred tattoos and metallic charms that are literally worn on and within the body. A group of the talismanic silver charms originally taken from a prisoner on the Andaman Islands is displayed next to a seated figure of a Shan man who wears tattoos and metallic charms. They were implanted under the skin and are visible as rows of dots on the figure’s arms and neck. Although the origins of the figure remain unclear, it is possible that it was made during the colonial period as a souvenir for a foreigner.

The design of the show encourages visitors to make cross-cultural connections as well as to look at the significance of certain groups of objects. So, a large bronze Buddha footprint, often found at the entrance to a temple, or positioned to face the main deity, is displayed here along the central axis of the gallery, in alignment with the showcase of ritual objects for an altar, as one might find in a temple. The illustrated descriptions of the motifs on the footprint are particularly helpful and not often found in museum displays of this type of material.

The altar case was, according to Green, ideally intended to be a contextual display in which offerings could be incorporated to illustrate their importance in the ritual of merit-making. It is worth stopping again at the entrance to the show to view the offerings—colorful money trees, lotus flowers, and daily items for monks, complete with plastic bucket. Unfortunately, the strict conservation requirements mean that integrating contemporary materials with more fragile, older museum artifacts remains a challenge for curators who want to bring cultural context into an exhibition. That said, this carefully researched exhibition, which included consultation with Theravada monasteries in the UK, has done well to bring unseen objects to light. Together with a lively lecture program and special hands-on workshops with local Thai and Burmese communities, it inspires curiosity and a desire to travel and experience these anything-but-austere traditions at first-hand.

Heidi Tan was principal curator for Southeast Asia at the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore. She is an Alphawood Foundation scholar currently pursuing a PhD at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

Pilgrims, healers, and wizards: Buddhism and religious practices in Burma and Thailand will be on view at the British Museum until 11 January 2015. All the objects in the show are from the British Museum’s own collection. Admission is free.

Unless otherwise stated, all photographs in this article are by the author.

References

Denes, Alex. 2012. “Trees of offering: the Salak Yom festival in Lamphun province.” In Enlightened Ways. The Many Streams of Buddhist Art in Thailand, edited by Heidi Tan, 56–61. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum.

Skilling, Peter, Jason A. Carbine, Claudio Cicuzza, and Santi Pakdeekham, eds. 2012. How Theravada is Theravada? Chiangmai: Silworm Books.