his write-up, in two parts, is based on a presentation given by the author at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in October 2018, during the symposium “Historical Perspectives on the Culture and Practices of Tantric Buddhism.” The topic is Performative Iconography. The audience was a select panel of world specialists in tantric Buddhist religion and art, convened in preparation for a groundbreaking exhibition on tantra opening in 2022, under the direction of John Clarke and Ian Baker, and touring worldwide.

These Nyimgma school cham dancers attain the “apotheosis of mystical understanding” by embodying the tantric deity as dance. My late mentor, Dr. Peter Brinson of the Laban Center for Movement and Dance, told me that the best thing I could do with my exposure to ancient Asian dances would be to use it to expand the concept of knowledge in the West. He urged me to investigate the origins and the roles of dance. Eastern cultures perhaps, had more inclusive and complex concepts of knowledge than Western culture?

The religion of the West begins: “In the beginning was the Word . . .” Aquinas and Descartes succeeding in denigrating the body in favor of intellectualism. And this remains the predominant thinking in the West. In India, by contrast, the universe begins with the dancing Shiva Nataraja, who, in his cosmic dance of creation and destruction, transcends as a philosophical symbol of being. Dance is the highest expression of the deepest truths. It is important to recognize where dance is present at the origin of religion, language, philosophy, and art . . . and where it is not. This gives insight into the power of performed iconography and the use of dance to animate. Ritual performance can be the re-creation of a primal act, evoking the ultimate.

Photo by Gerard Houghton. From Core of Culture

Vajrayana Buddhism originated in Tibet when a dancing wizard, Padmasambhava, used dance to subdue obstacles to the building of the first Tantric Buddhist monastery in Tibet at Samye. He enacted a mandala site with dance and a ritual dagger or phurba. Whole canons of Black Hat dances thrive throughout the Himalaya even today. They are wizard dances of the type Padmasambhava used at Samye, designed to facilitate coded information between dancers and transmute energy in tantric rituals.

Knowledge of dance practice, history, and meaning enhances the study of Buddhism, a religion with perhaps more dance than any other—and in the case of Vajrayana, a religion born with an act of performed iconography when Padmasambhava subdued the demons obstructing the construction of Samye Monastery, a mandala, with a dance. This was the birth of Vajrayana Buddhism in Tibet. Dance is the core, the heart, the first expression, the protective essence of Guru Rinpoche. Dance is the vital origin and repository. Tantra is performed spirituality.

The most ancient Chinese script, the oracle bone script, includes an ideogram for the word dance, depicting a dancer carrying branches for ritual dance. This is important because dance appears with the origin of language and art simultaneously. Dance has been in the Chinese art and literature record since the dawn of time.

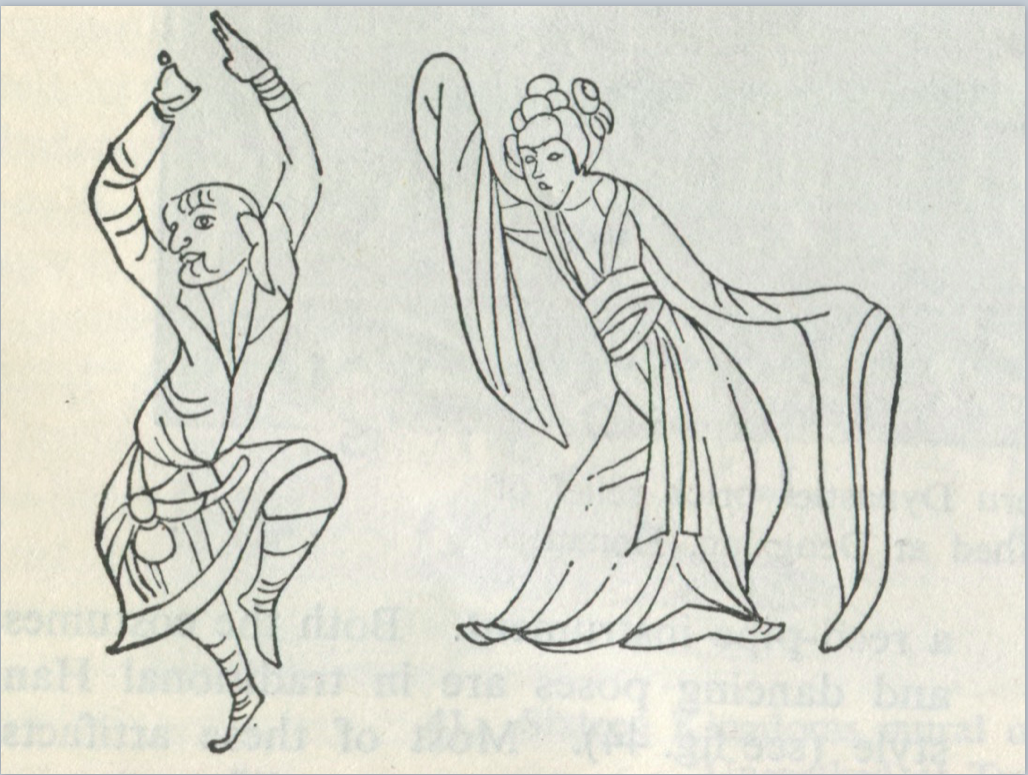

It was in China, under Prof. Mme. Wang Kefen, that I learned the Chinese method of conducting dance history by using art history. Depictions of dance reveal the integration of performed practices as they moved along the Silk Road. Dunhuang is a veritable Rosetta Stone of ancient dances. The explosion of movement practices created a parallel freedom in artistic depiction. The archaic Taoist deities, and flying feitian, are masterful acrobats of the heavenly realms. Religious icons never had such dance technique.

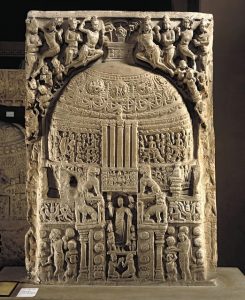

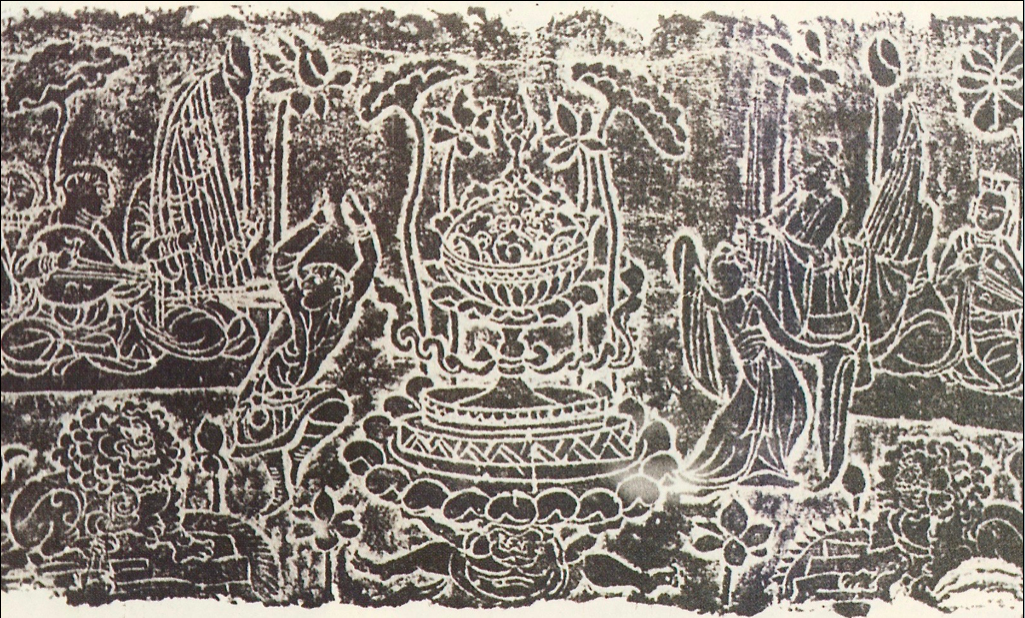

This surprising rubbing from a Tang dynasty stone monument shows a Buddhist court dancer dancing with a Sogdian folk dancer around a symbol of the Dharma. This is literal iconography being performed to represent a social and religious reality. The Sogdian dancer is a veritable meme in Chinese and Silk Road art. Both engravings are generic to the point of being symbolic. Dancing does not merely show the integration, dancing is the integration. Dancing is the iconography performed.

Photo by Jonathan Kendrew for Core of Culture

Photo by Jonathan Kendrew for Core of Culture

The Eight Manifestations of Guru Rinpoche is a fundamental iconographic schematic in Himalayan Buddhism. In these two images from Ladakh and Bhutan, we see that the cham called “Guru Senge” is nothing other than iconography performed and become actual. The presence of these icons at a festival is something like a family reunion.

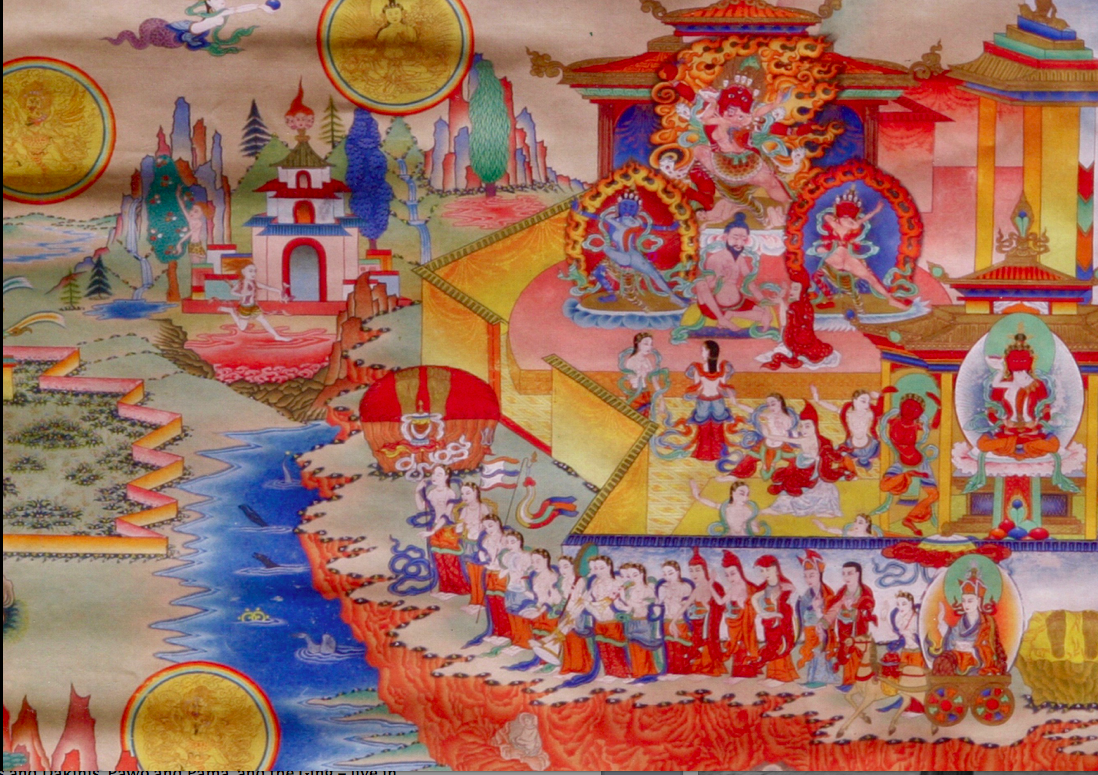

Guru Rinpoche’s Sambogakaya Palace in the other dimensions, Zangdopalri, is a mystical dance generator. Not only do Guru Rinpoche and his two consorts, Mandarava and Yeshe Tsogyal, figure prominently in yogic visions in which dance is shown and taught, but many otherworldly beings who people Buddhist art and festivals—such as Dakas and Dakinis, Pawo and Pamos, and the Ging—live in Zangdopalri, and revel in their anti-gravity freedoms.

The iconography is alive in the visions, and then, thanks to mystical experience and its successful conveyance, it becomes embodied dance in people other than the yogi. There is a direct, lasting, and empowering connection. Many of these yogic dances survive today, hundreds of years since their creation. The late Chogyal Namkhai Norbu (1938–2018) revealed several sets of yogic dances in the 20th and 21st centuries. The dances were taught to him by a Goma Devi, by dakinis and dakas, and other visionary dancers. Treasure Revealers (Tib: terton) revealing Treasure Dances (Tib: terhcam) is a tradition lasting centuries in Buddhism. Dances born in yogic visions of dancing characters are ubiquitous in Vajrayana Buddhism.

Ashi Kesang Choeden Wangchuk

In this rare painting of Zangdopalri owned by the Queen Mother of Bhutan, we see a Treasure Revealer, Chogyur Lingpa (with a red pointed hat, on a yellow ground, below the main red wrathful deity). He is dancing with dakinis, learning their dance. This painting was created according to Chogyur Lingpa’s description of his vision.

Finally, this presentation closes with two examples of complex performative iconography in Vajrayana. First is a sacred and private mural of the Zhabdrung, the founding ruler of Bhutan, which was destroyed when Wandu Phodrang Dzong burned down. This mural depicts an act associated with the founding of Bhutan. The Zhabdrung was an adept in dance and tantra. He is performing black magic using a dance.

What is significant about this sacred mural is the depth of the “performativity” and psychic meditation technique required to appreciate the full set of factors contributing to Bhutan’s coming to be. The Bhutanese believe deeply in their protective deities as these deities have so far never failed them. The mural depicts the Zhabdrung and others performing a tantric rite. The true subject of the painting, however, is the conjured visualization of Raven-headed Mahakala produced by the depicted danced rite.

The conjured deity, in an act of psychic warfare, kills a rival king at the instruction of the Zhabdrung. Once the murder is complete, the Raven-headed Mahakala returns to the Zhabdrung and performs a dance with a retinue of three. This dance is now an actual dance, performed since 1616 until the present day, in private, in the most sacred ceremonies at Thimphu Dzong. The four Raven-headed Mahakala masks reside atop life-sized gold statues of Raven-headed Mahakala, behind an altar in the dzong’s temple. Once a year, the four top dancers remove the masks and perform the dance . . . that is the subject of this mural.

The final example shared here is the Thimphu Drubchen, private danced ceremonies held inside the main monastery courtyard, readying for the public Tsechu festival. This process of daily drubchen dancing by the full contingent of dancers in the monk body, is informed over two weeks by actualizing, in meditation and dance, a series of successive iconographies. Each of 36 dancers goes through this mental and embodied process:

First, developing from a simple figurative thangka of the heroic manifestation of Guru Rinpoche . . .

Bhutanese thangka painting, 19th century. From Core of Culture

Then the object of meditation becomes an abstract geometrical mandala of Guru Rinpoche’s “tantric form” as the wrathful deity Gong Du. This is held in the mind as the long dance is learned and rehearsed every day.

Thimphu Dzong, 2007. Photo by Gerard Houghton for Core of Culture

Next, the object of meditation becomes figurative and complex: a thangka of Guru Rinpoche in wrathful aspect as Gong Du, surrounded by dancing wrathful deities. The head lama of Bhutan, the Je Khenpo, assigns each dancer a specific depicted Dharmapala to embody as the final public result of “the deity being brought out” over two weeks, through a succession of meditated icons, and more than 100 hours of dancing.

Punakha, Bhutan. From Core of Culture

Concluding, it is good to remember, regarding performative iconography, that when the dance you see looks like this . . .

. . . there is a performed iconography, a dance underneath and within, that looks like this.

Photo by Gerard Houghton for Core of Culture

See more