The 20th Biennial Conference of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB), jointly organized with and hosted by Jungto Society, was held in South Korea from 24–30 October under the theme “Buddhism in a Divided World: Peace Planet, Pandemic.”

The forum, which was divided between the autumnal mountain idyll of Mungyeong in the south of the Korean Peninsula and the 21st century metropolitan bustle of Seoul, brought together almost 100 speakers and attendees, members of INEB from around the world, along with INEB founder and renowned social activist Sulak Sivaraksa and Ven. Pomnyun Sunim, the founder of Jungto Society and Patron to INEB. The speakers included distinguished teachers, scholars, and prominent engaged Buddhist activists, who presented, examined, and discussed a wide array of topics that broached the core themes of the roles and obligations of engaged Buddhists in today’s divided and troubled world.

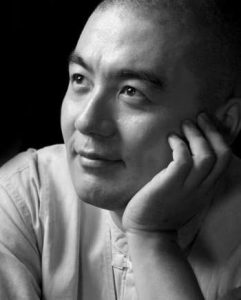

Among the notable speakers at the week-long forum was Sai Sam Kham, a former executive director of Metta Development Foundation in Myanmar and a member of INEB’s Executive Committee, who gave a powerful keynote address during the conference’s opening session.

Sam is a PhD researcher at the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS, The Hague), Erasmus University Rotterdam. He is also a member of the “Commodity & Land Rushes and Regimes: Reshaping Five Spheres of Global Social Life (RRUSHES-5)” project led by Prof. Jun Borras. As part of this project, Kham’s research explores how rural agrarian land politics shape the character and trajectory of national political regime transition in Myanmar, and vice versa.

Kham’s keynote speech, “Peace, Planet, Pandemic, and Engaged Buddhism: From a Divided Myanmar to a Divided World,” which opened the conference is reproduced in full here.

Vahujana hitara, vahujana sukhara!

Dear Ajahn Sulak, Ven. Pomnyun Sunim, Venerables, and kalyana-mitas from INEB, I am glad to see all of you again. I am very grateful to Ven. Pomnyun Sunim and to Jungto Society for allowing us to be in this beautiful training center and for providing such warm hospitality. I am also very grateful for the generosity of the donors and the volunteers.

This is the first INEB conference since the previous biennial conference at the Deer Park Institute in Bir, India in 2019. The virus that causes COVID-19 started spreading in late 2019 and turned into a deadly global pandemic the following year. Sadly, we saw the loss of millions of precious lives, including those of our loved ones, and the suffering brought to us by lockdowns and economic breakdowns. I am sure that many of us have been touched by these tragic experiences. Similarly, over the past three years we have seen how climate change has affected millions of lives, and the spread of violent political turmoil and war. Despite these challenges, all of us are here meeting again. All still alive and continuing our mission to bring about positive change in society and in the world. It is indeed a blessing that we can see each other again and work together again.

It is an honor for me to present this keynote thought-piece for this conference. Thank you very much for this opportunity! Although I feel undeserving, I would like to offer some thoughts related to the key topics of the conference. To be honest, these are more questions from a puthujjana (an ordinary person) than answers to the problems that concern us—questions that have troubled me for months and years. And to some extent, these are also questions that the generations leading the Myanmar Spring Revolution are grappling with. Indeed, they are questions about social justice and Buddhist ethics that may resonate with all of us because the questions I have are linked to our roles as engaged Buddhists, either as individuals or institutions, amid the fast-developing threats from conflicts, climate change, and the current and future pandemics. For my remaining time, I would like to share some thoughts on the key themes of our conference—Peace, Planet, Pandemic—weaving between local and global perspectives, from divided Myanmar to the divided world.

Peace

While re-reading the book Dharmic Socialism by Phra Dharmakosacarya Buddhadasa Bhikkhu recently, I noticed that the editors of the English-language version had commented on the timeliness of the book as humanity needs to change its course from potential destruction and annihilation due to the growing risk of nuclear conflict. The book was first published in 1986. In three years, this book will be 40 years old, and yet the concerns for peace seem to be timeless. As if history has repeated itself once again, we are gathering to talk about tumultuous politics, conflicts, and how we can, perhaps, prevent them. Myanmar is literally burning while we are talking here. An aerial bombing in northern Myanmar by the military junta just a few days ago killed 60 people and wounded hundreds. One of the victims is an acquaintance. For decades, the ever-present risk of war on the Korean Peninsular has been a living nightmare for our brothers and sisters in Korea. The war in Ukraine is escalating every day, and there is now the highest prospect of nuclear war in 60 years, and US President Joe Biden has warned of an approaching nuclear armageddon.

Wars have been waged because of differing ideologies, territorial claims, the desire to access and control resources, and sometimes because of the egos of world leaders or their hatred or desire to beat a people into submission. Some wars were waged out of sheer greed to plunder a country, or because of an imperialist desire to dominate through brute force and hegemony.

At the same time, violent armed conflicts have taken place because of an enabling environment and the economic systems benefiting from it. They are what Hannah Arendt would call “the banality of evil.” The enablers may be white-collar workers, like some of us. They may go to their offices 9–5, and then return to their families as loving fathers or mothers. But they may be the same people supporting these wars, knowingly or unknowingly. Behind every war or authoritarian regime, there are businesses and industries directly benefiting. Many of you will remember the US multinational giant Halliburton and its links through asociates to the war in Iraq. They benefited to the tune of US$39 billion from contracts with the US government. In total, contractors, including private security, logistics, and reconstruction, earned US$138 billion from the Iraq war alone. (Fifield 2013)

Myanmar Brewery, which is owned by Myanmar’s military, has collaborated with Kirin Beer of Japan. One of its most famous products, Myanmar Beer, brought US$22.7 million in income just from the first three months of 2020. (Justice for Myanmar, 2020) Kirin’s investors include prestigious organizations from all around the world—such as the Norwegian Sovereign Fund. The Norwegian government is one of the biggest donors to the multilateral Joint Peace Fund that supported the failed Myanmar peace process. Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise, a state-owned business with deep ties to Myanmar’s military, has worked with Total, Shell, Woodside, and Posco Daewoo. In 2019, the income from Total was US$257 million. (Justice for Myanmar, 2021a)

With such disposable income, and without any concern for accountability, Myanmar’s military can do whatever it pleases, including funding the Rohingya genocide and the current war crimes against the Myanmar people. The UN system is utterly useless for preventing such brutality—including the Russian invasion of Ukraine. My point is that for any war taking place around the world, there are business interests as well as businesses that are bankrolling the conflict. And we need to hold them accountable. Some governments are handing out peace funds and peace prizes with their left hand, while funding wars or selling weapons with their right hand.

Let us see, for example, who has sold or is selling weapons to Myanmar . . . From 1990–2016, the biggest weapons suppliers to Myanmar’s military were China, India, Israel, Russia, and Ukraine. (Asrar 2017) That is correct! Until the recent Russian invasion, Ukraine supplied armored vehicles and missiles to Myanmar’s military, which were then used in the campaign against the Rohingya and other minorities. In 2019, an amphibious LPD [landing platform dock] warship from South Korea was transferred to the Myanmar navy with a price tag of US$42.3 million. The warship can carry three helicopters, 16 tanks and armoured vehicles, and more than 500 soldiers. This type of warship is used to conduct military operations in river deltas. The contract was negotiated in 2017, while the genocide was ongoing, and was concluded after 2019. The ship is already in use by Myanmar’s military. Now the Korean police are in the advanced stages of investigating POSCO International, Dae Sun Shipbuilding & Engineering, and South Korea’s Ministry of National Defense regarding alleged violations of South Korea’s Foreign Trade Act for selling a warship to Myanmar. (Myanmar Now 2022)

I apologize for all these details, but they are to highlight how seemingly harmless businesses, such as a brewery or an energy company, can fuel war and aggravate the suffering of people. You would probably not be surprised to learn that arms suppliers to Myanmar also include some European countries, such as France. (Justice for Myanmar, 2021b) China, France, and Russia, three countries out of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, are suppling weapons to the genocidal military in Myanmar. How on earth can the people of Myanmar believe that these countries want peace for Myanmar? How on earth can the UN Security Council fulfill their mandate for global security? This is the experience of just one country. I wonder what other countries would say. I don’t think there will be any great difference.

My question to all of us today is what can we do in such situations? As individuals, as institutions, as movements, as engaged Buddhists, how can we address the evidently contradictory roles played by the UN Security Council and its permanent members? How can we hold them accountable? If the UN systems don’t work, what are the possible alternatives? At the same time, how can we hold weapon suppliers accountable? People are dying by the millions because of wars, while they are reaping billions of dollars in profits. And they don’t need to be accountable for a single life lost, beyond putting up a veneer of PR campaigns and so-called “corporate social responsibility” programs.

Another key concern in terms of global peace and stability is the rise of what people call the far right or right-wing nationalism, or what I call fascism. Some of these fascist political movements have taken the form of religious nationalism, such as the ultra-nationalist Buddhist organization Ma Ba Tha in Myanmar and Hindutva Hindu nationalism in India. The rise of the far right is also very apparent in Europe and the US. Italy has just installed a prime minister who idolizes Mussolini. Polarization caused by political, social, and economic inequalities are the main reasons, as we know. These contestations often take violent forms. We do not need to recall our painful memories of World War II and the Holocaust. How should the inward-looking, delicate, non-violent, meditating Buddhist address these violent forces? Apparently, liberal electoral democracy alone cannot solve the challenges posed by fascism. I think our commitment and moral responsibility is calling us to take on this issue. What kind of pre-emptive collective measures can we take to stop fascism from advancing?

Now, please let me move on to the issue of our planet and climate change!

Planet

I will not go into detail about what is climate change and how it is affecting humanity and the planet. Most of us are familiar with the issue and it is one of the repeated key themes at INEB conferences.

Here, instead, I would like to highlight a few points for us to consider when addressing climate change. We all know how our way of managing economies, our patterns of production and consumption, require fundamental change—not quick fixes, and definitely not the capitalist solutions that are being proposed as technological fixes to solve the problems. It is also our attitudes and values as a civilization that need serious re-examination. The influential Thai monk and philosopher Phra Buddhadasa Bhikkhu said:

Those who hold the “eat well, live well” view do not have any limits. They are always expanding until they want to equal the gods. . . . Those who hold the “eat and live only sufficiently” view represent moderation—whatever they do, they do moderately. This results in a state of normal or balanced happiness (prakati-sukha). They will have no problem of scarcity, and there will be no selfishness.

(Buddhadasa 1993)

The master’s comment stands in stark contrast to the consumption and consumerism which drive the global growth economy. His comments disagree with the proponents of the free-market economy and neoliberal capitalism. As we can also see in Jungto Society, mindful consumption is an important practice from which we can all learn.

At the same time, we must be cautious because the issue of climate change is being politicized and becoming an industry and a market in its own right. It is a billion-dollar business that includes renewable energy solutions, carbon-capture projects, climate-smart seeds/climate-smart agriculture, and many other proposed green solutions. Some of these solutions are not wrong in themselves, but many initiatives are causing harm to communities, especially those in poor countries or poor agrarian communities. If we are not careful, we will fall victim to capitalist solutions for climate change. Some of these projects come with good intentions but are poorly thought through or implemented, and have been criticized as greenwashing and green-grabbing or green colonialism.

A few years ago, a national park in northern Myanmar was expanded with support from an international conservation group. It caused so much pain for the ethnic minority communities living there. There is a mass of literature highlighting how renewable energy policies in developed countries have led to a land-grab for palm oil, sugarcane, and maize production, especially in poor countries with very little land tenure security for local farmers. Climate-smart seeds or climate-smart agriculture technologies are controlled by corporates, not farmers. In Myanmar, controversial hydropower dam projects were shoehorned in among the renewable energy proposals in the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) of the Paris Agreement. I wonder what other countries in this conference have to say about their experiences.

Many of us are promoting agro-ecological farming practices, food sovereignty, and farmer’s movements to address the issue of climate change and food security. Many of us know that agrarian justice and food justice initiatives for farmers must go hand in hand with climate justice. In addition, I would add land justice as an important issue. We must be cautious to look at not only physical land-grabs but also how land is being defined and who is making and controlling these definitions. This is because if someone can control the meaning of land, they can easily shape the definition to enable land-grabs. Some have done so through changing laws and policies.

During Myanmar’s experiment with democracy, we introduced legislation in 2012: the Vacant, Fallow, and Virgin Land Management Act. But who defines what is vacant, fallow, or virgin land? In 2016, during the National League for Democracy’s rule, the law was changed and customary land practices were rejected. Two months after the revision was enacted, when the improbable deadline to apply for land registration expired, millions of smallholder farmers became legally landless. More than 19 million hectares of land that was defined by the state as “vacant, fallow, and virgin”—which simply meant undocumented land used by generations of small farmers who practiced customary land tenure—was now ready to hand over to any companies who could pay the price. This was the biggest legal land-grab in Myanmar’s history, and the state’s encroachment on the rights of the indigenous people and their right to self-governance. Changing land laws, and giving land registration and leases is how land has been snatched from the farmers, who have been using and caring for the land for generations. Instead, now they have a piece of paper promising limited access duration and limited rights.

This land commodification is known as market-assisted land reform. Within the politics of climate change, small farmers are being blamed as carbon producers or polluters, while big agribusiness are being promoted for their “efficiency” and therefore given priority access to land. This is a widespread global policy of which we must be extremely cautious. Land is not only for agriculture or for any kind of production; it has many other functions, such as social reproduction, as well as cultural and spiritual values. The right to land is the right to life itself. I hope INEB can become more engaged in the issue of land rights.

Fundamental to agro-ecological farming to address climatic and environmental issues, we must remember that the struggles of farmers are not technical or bureaucratic. Rather, they are political and we therefore need a political solution. We are not together in this, when it comes to climate change problems. Poor people suffer more. Therefore, any proposed climate solutions must recognize their voice and their right to represent themselves.

Now please allow me to move to my comments on the pandemic!

Pandemic

The epidemiologist and evolutionary biologist Rob Wallace combined the study of epidemics with political economics and social studies when he investigated how certain viruses emerge, how they manage to quickly spread, and the social and economic conditions that allow pandemics to happen. Wallace’s studies point to the capitalistic mass production of food, especially poultry and pork, as a key area of concern. (Papas, Willmeng, and Kwon 2021) When structural adjustments in Africa forced an expansion of industrial agriculture into deep forest regions, the sensitive ecological balance was broken and reserves of new pathogens were exposed. In this way, the emergence of Ebola has been linked with economic policies and capitalistic agriculture. When big agribusiness and monoculture took the land and dominated mainstream food production, rural farmers were forced to engaged in marginal food sectors such as wild foods. Meat produced by the corporates and big farms is sold next to wild animals and bush meats.

In 2016, Wallace published a book provocatively titled Big Farms Make Big Flu. Since then, he has predicted that pandemics stemming from this mode of capitalist food production, and restrictions on people’s mobility, as being inevitable. It is not a matter of “if” but a matter of “when.” For now, he warns that we are not free of the COVID-19 pandemic, as many of us would like to believe. And he suggests that we need to do more than offer vaccines. In terms of controlling the spread of the virus, Wallace sees the need for non-pharmaceutical solutions such as testing, tracking, and isolating, and, most importantly, providing support to low-wage workers whom we inappropriately refer to as “essential workers.”

Unless we change the ways and means of production, circulation, and consumption of our food, there will be pandemics of one kind or another, or worse, there could be a combination of one or more pandemics, climate disasters, and political instability or war. This point may sound like an alarmist call, however from Myanmar’s experience with COVID-19 combined with conflict and a violent military-led coup, we know that the possibility is very real.

INEB has been working with various partners across the region on organic agriculture and agro-ecological farming. To address the agribusiness model that produces pandemics, we must take our food sector seriously. Myanmar, with its primitive health sector, has survived the pandemic largely because of its sharing economy, moral economy, and a culture of caring. I am sure many of you have great stories to share which come out of our collective struggle against the global pandemic and its broader consequences.

In conclusion, I would like to discuss:

Confronting difficult questions for engaged Buddhists

How can engaged Buddhism address the dilemmas, contradictions, and paradoxes within Buddhism and its different schools and traditions? The issues I am going to raise are nothing new, yet they continue to confront us persistently. What can we learn from these common issues? How can engaged Buddhists address them? And how, in turn, can they help us understand the main theme of our conference “Peace, Planet, and Pandemic”? The first issue is related to how we understand and apply the Buddhist concept of karma or kamma. The second issue is how Buddhists choose between nonviolent and violent means, and how we understand them. I can tell you that these are fundamental questions that come out of confronting the most violent repression in Myanmar’s history while being a practicing engaged Buddhist. Amid the deadly coup in Myanmar and the subsequent revolution and resistance movement, many Buddhist monks, as well as Christian priests and Muslim leaders, are fighting injustice at the risk of their own lives. Some monks have disrobed and now carry weapons to the fight.

At the same time, there are senior venerables (including the renowned Sitagu Sayadaw) and their followers who openly support the Myanmar military and the coup. They believe that the military is the only community capable of protecting Buddhism. How can the sangha support such unspeakable violence? This irreconcilable moral destitution of towering Buddhist leaders makes millions of Buddhists feel that the earth beneath their feet has shattered. Young Buddhists are starting to question the relevance of Buddhism and the monastics in their lives. Dismayed by the corruption and wealth of some monks, young people are contemplating a Buddhist order led by laypeople. Sadly, for them, sangham are no longer a saranam for seeking refuge. Young women are asking why would they follow a religion that considers them “dirty” and treats them with contempt. Compared with men, women are the ones who are more regularly faithfully donating and supporting Buddhism. “Women’s bodies are dirty,” “bhikkhunis are not welcome,” yet their donations are welcome. How long can such contradictions be maintained in the long run? What good can the discrimination and exclusion of women in the sangha bring to the Theravada tradition? With the ongoing revolution, established ideologies and values are crumbling. A new Myanmar is quickly emerging. Is Theravada in Myanmar ready to reform or risk extinction?

Before and since the violent military coup in Myanmar in 2021, we have seen an unholy alliance between Buddhist nationalists and the military. Although the majority of Myanmar’s population are Buddhists, we have a long-standing fear of a Muslim takeover that is introduced to us as children. Although this fear is unsubstantiated, it is widespread. Being a pariah nation under decades of socialist dictatorship that practiced a closed-door foreign policy may have exacerbated religious conservatism, xenophobia, and islamophobia. Whenever something shameful involving the Buddhist clergy is reported, we shrug and blame the “bad apples,” the individuals. This, we insist, has nothing to do with Buddhism. Gradually, questions have been raised as to whether Buddhism as an institution has been responsible for helping successive military regimes in Myanmar to claim political legitimacy. Finally, there is the question of the concept of kamma—or at least the way that Theravada Buddhism in Myanmar has interpreted and taught kamma—and whether it is being used to justify a culture of impunity.

In the Myanmar Theravada tradition, at least as understood and practiced by the majority Buddhists, kamma is a form of determinism that is dictated by the “good” or “bad” kamma one has accumulated in past lives. This position creates two main problems. One is victim-blaming: if a person suffers from an injustice or an affliction, for example sexual violence, it is because of “bad kamma” the person earned from their behavior in past lives. The second issue is that of justice and accountability: this kammic position says that the wheel of kamma will take care of the wrongdoings of a person, so there is no need to seek external justice. Punitive justice is seen as an undesirable form of revenge instead of a deterrent. Instead of seeking punishment, the victim is advised to forgive and move on.

There are many cases of mismanaging domestic abuse or sexual violence through traditional arbitration or local justice systems that are dominated by this Buddhist worldview. Many military dictators have enriched themselves with wealth plundered from the country. However, the soldiers who risk their lives on the frontline believe that they deserve it because of their good karma. Why should we be complaining, right? People do go to court or seek alternative routes to justice, but this traditional view is the most prevalent attitude among the general public when it comes to questions of justice and accountability. The question now is: has the teaching of Buddhism in this way unwittingly strengthened a culture of impunity in Myanmar?

In the book Rethinking Karma: The Dharma of Social Justice, editor Jonathan Watts writes:

This lack of engagement with social injustice has created a moral myopia within traditional Buddhist societies towards the fundamental forms of structural and cultural violence underpinning the more visible acts of violence and oppression. The common understanding of karma often serves to perpetuate structural and cultural violence, such as sexism, classism, and political oppression.

(Watts 2014)

What is your experience in your own country and your own society? How do engaged Buddhist approach justice and accountability? How do we address impunity? Shouldn’t kamma, which means action, be redefined as our own agency to break down mechanisms of structural and cultural violence?

Venerables, ajahns, and kalyana-mittas: some of you might have visited Myanmar and met my friends and colleagues there. Many of these young Buddhists, who are trying their best to foster social change in their communities, are now joining the revolution. Some of them have taken nonviolent action, but many are now participating in the armed resistance. Some have become high-ranking revolutionary military officers. It is sad, but I can tell you that I am very proud of them. My respect for them has never changed. Young people are being forced to choose this path—not because they enjoy violence. In these difficult days, I am re-examining and rethinking my own position. I used to think that I would rather die than be forced to fight in a war. Having grown up on the frontlines, I am no stranger to conflict and I hate war. But now I am asking myself: what I will do if violence knocks on my door? If my loved ones are the victims of a brutal military campaign, will I flee? Will I pray and meditate? Or will I take arms to protect them?

Since the time of the Buddha, there have been wars. How do Buddhists engage in violence? Any killing or harming other beings, not only human beings, is considered akusala; unwholesome. And yet, in our daily lives, we enjoy eating meat. We let poor people, the butchers, commit the killing. We outsource our bad kamma to the lower castes or classes. We let the poor people sin and suffer in their later lives on our behalf. And we get away with that! How does that work? How do Buddhists reconcile such dilemmas and contradictions?

In his interview for the Insight Myanmar Podcast, Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi raised the following questions related to the gray areas of applied sila and moral dilemmas faced by Myanmar in the midst of this crisis:

[In] going against the precept, you’re doing so because there’s an overriding moral obligation or commitment under that situation to protect the life of people in danger. This doesn’t involve reinterpreting the precept such that it loses its moral force; it’s understanding there are different moral obligations in play. . . . For example, what does one do if you were to find yourself in a kill-or-be-killed scenario? What types of force are permitted if this is might be the only way to stop rape? Or torture? Or death of children? And if one decides to use force in such circumstances, what will the karmic consequences be? And can one commit violence without having ill will?”

(Insight Myanmar Podcast 2022)

The revolution has dramatically changed Myanmar society. That’s what a revolution should do. It is not all about bad and tragedy only. It is tragic, but the light of many stars shines out of this deep darkness. In times of great suffering, there are also great compassion and great sacrifices. In such times, many contradictions, many difficult questions and taboos about Theravada Buddhism in Myanmar that have long been swept under the carpet have come out in the open. Young people are not taking such nonsense anymore. We Buddhists must either confront the difficult questions and seek understanding, if not answers, or we risk losing an entire generation. That could well be the end of Buddhism in Myanmar. I know I am being dramatic, but it almost becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of which Myanmar Buddhists live in fear. We, the older generations, owe the young these answers if we want to see our lineages and teachings continue. On so many occasions, Ajahn Sulak has reminded us that Buddhism must be relevant for the modern world. When it came to difficult questions, to reformation, and to reinterpretation, Phra Buddhadasa Bhikkhu never shied away. He bravely and brilliantly reimagined a political model. The same can be said for Dr. B. R. Ambedkar and the movement to liberate the Dalits of India. There is so much we can learn from the Ambedkarites

In confronting the key issues raised by this conference—peace, planet, and pandemic—there is so much that needs to be done. We need mass mobilization and mass movements. We need solidarity beyond the narrow scope of nation states. I am at a loss for words to express how grateful I feel for the solidarity, compassion, and generosity shown by INEB and Jungto Society for Myanmar and for other members of INEB who are in need.

Let me conclude with this final quote. In his recent interview with Buddhistdoor Global, Venerable Punyum Sunim said that we must still keep doing the right things we are already doing, without expectation or attachment for whether our actions will come to fruition or not. He says:

No matter how beautiful the Buddha’s teachings are, they are effectively useless unless they can lead people to lift themselves out of their suffering.

(Lewis 2022)

Therefore, let us work together to help ourselves, to help our planet, and to help other beings!

Thank you very much for your attention!

References

Asrar, Shakeeb. 2017. “Who Is Selling Weapons to Myanmar?” Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/9/16/who-is-selling-weapons-to-myanmar

Buddhadasa Bhikkhu. 1993. Dhammic Socialism by Buddhadasa Bhikkhu. Bangkok: Thai Inter-Religious Commission for Development.

Fifield, Anna. 2013. “Contractors Reap $138B from Iraq War.” CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2013/03/19/business/iraq-war-contractors/index.html

Insight Myanmar Podcast. 2022. “Episode #104: The Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi Returns”. https://insightmyanmar.org/complete-shows/2022/5/14/episode-104-the-venerable-bhikkhu-bodhi-returns

Justice For Myanmar. 2020. “Human Rights Activists Respond to Kirin’s Myanmar Sales “Surge”, Which Netted Approximately USD$22.77 Million in Q1 2020 Profits for the Myanmar Military”. https://www.justiceformyanmar.org/press-releases/human-rights-activists-respond-to-kirins-myanmar-sales-surge

———. 2021a. “How Oil and Gas Majors Bankroll the Myanmar Military Regime”. https://www.justiceformyanmar.org/stories/how-oil-and-gas-majors-bankroll-the-myanmar-military-regime

———. 2021b. “UN Security Council Members Complicit in Arms Sales to Terrorist Myanmar Military Junta”. https://www.justiceformyanmar.org/press-releases/un-security-council-members-complicit-in-arms-sales-to-terrorist-myanmar-military-junta

Lewis, Craig C. 2022. “Ven. Pomnyun Sunim: Buddhism in a Divided World” in Buddhistdoor Global. https://www.buddhistdoor.net/features/ven-pomnyun-sunim-buddhism-in-a-divided-world/

Myanmar Now. 2022. “Korean Police Investigating Illegal Sale of Warship to Myanmar”. https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/korean-police-investigating-illegal-sale-of-warship-to-myanmar

Papas, Mike, Cliff Willmeng, and Tre Kwon. “Capitalism Breeds Pathogens: An Interview with Epidemiologist Rob Wallace” in Left Voice, 9 July 2021.

Watts, Jonathan S., ed. 2014. Rethinking Karma: The Dharma of Social Justice. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

See more

2022 Public Symposium | Seoul, Korea (INEB)

The 20th Biennial INEB Conference in South Korea (INEB)

International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB)

Jungto Society

Jungto Society International

Related news reports from BDG

Engaged Buddhism: 20th Biennial INEB Conference Concludes in South Korea with a Commitment to Action, Peace, and Change

Engaged Buddhism: 20th Biennial INEB Conference Commences in South Korea

Engaged Buddhism: INEB to Host Public Symposium: “Roles of Spirituality & Faith in a Divided World”

Engaged Buddhism: INEB’s SENS 2023 Transformative Learning Program to Commence in January

Engaged Buddhism: INEB Launches Sangha for Peace to Tackle Regional Religious and Ethno-Nationalist Tensions

INEB, Clear View Project Launch Humanitarian Appeal for Buddhist Monastics in Myanmar

Related features from BDG

Ven. Pomnyun Sunim: Buddhism in a Divided World

Compassion and Kalyana-mittata: The Engaged Buddhism of Sulak Sivaraksa