According to the Lord Buddha, man’s “being-in-the-world” may be analyzed in terms of two coexistent parts that are dependent upon one another in what we may call a psychophysical sense. The mind could not exist without the body, and the body could not exist without the mind.

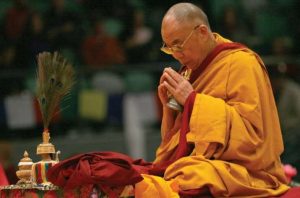

The culturally influential Thai monk Luang Phor Viriyang Sirintharo observed in the opening paragraph of his Meditation Instructor Course I. (p.1):

The body and the mind are intimately connected throughout the lifespan. A person cannot live his life solely with either existence. During a meditation session, the mind and the body must be co-functional. To study meditation, the meditator must begin with studying the correlation of this co-function.

Once we understand that meditation practice depends on observing the balance of correlating factors of the mind and body, the initial insight we have—the first thing we realize—is that a balanced meditation practice goes totally and directly against the common, conventional worldly current of desire. It goes against the current of nourishing the mind’s cravings, wants, and needs. It goes against a state in which the craving mind is always grasping after the things it wants but does not essentially or necessarily need.

The way of mindfulness goes against this way of common, conventional worldly thinking and acting. It goes against the worldly way of craving for desire, for the satisfaction of selfish needs. Therefore, to reap the benefit of this insight, we must be prepared to make a complete, 180-degree about-face. A paradigm shift to adopt the directly opposite view to the way that people-in-the-world are constantly concentrating on their own momentary cravings and normally seeing things (and people) as just being there to be used as objects of the senses; there for the satisfaction and nourishment of pleasure and happiness—as many would say, with a sensual “eat, drink, and be merry” attitude.

To repeat this point for the sake of emphasis, we must make a paradigm shift to be able to see things in the directly opposite way to which everyday people see themselves and the world. This might otherwise be called “seeing the world as a source of self-nourishment for its own sake.”

We must come to realize that the needs of the mind and the body, and the resultant arising of the uncontrolled development of increasing desires for such over-nourishment, are actually the worst enemies of our happiness. They lead us down an inevitable road of frustration, dissatisfaction, and disappointment—a road that invariably leads to certain suffering in the long term.

In other words, we must come to a clear understanding that an attitude of “I want what I want, right now! And I’m not going to be satisfied until I get it!” is not the right view. It is certainly not the way to happiness, because such a view’ is based on a wrong understanding of “happiness,” as being the “nourishment of self-centered, egocentric needs.”

The common worldly view is the wrong view.

And why is this so?

To explain we must (for the purposes of observation and mental analysis at least) separate a human being into TWO component parts and examine: “what is the body?” and “what is the mind?”

Let’s take “what is the body?” first. Once we’ve understood that everything depends on nourishment, then we must examine the nature of the body to see it. Not for what we might like it to be, but for what it actually is, which the Buddha describes in a well-known, detailed, discourse as follows:

“In this body, there are head hairs, body hairs, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, tendons, bones, bone-marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, pleura membranes, spleen, lungs, large intestines, small intestines, gorge, faeces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, skin-oil, saliva, mucus, fluid in the joints, urine and so on.” (MN.119)

Is this you? Do you see your “self” in this way? The way a surgeon who is equally well trained in the Dhamma might see the body as just the way it physically is? Do you see the body the way the Buddha sees the body?

No? Then how?

In the same dialogue, the Buddha uses an analogy to compare the body to a “fathom-length-long sack,” the kind that normally contains grain, open at both ends. But instead of containing grain, we can imagine it is stuffed full with the above-mentioned body parts. And we can ask ourselves how we would feel if our own body-sack were being shaken so that we might see each of our body parts as it slowly slipped and slid out. And falling, we could observe these individual body parts as they slowly ran down into a heap upon the ground. We would have ample time to examine and contemplate each of these body parts individually, falling and accumulating there in a pile, with each just one of the many component parts of our own physical body.

How would we feel then? Would we be enamored with the physical body if we examined it in this way, as just a composite of components aware of its nature as a mere compound of connected individual parts?

One who meditates on the body contemplates oneself as just such a body made up of individual parts. And that’s a good starting point, a good place for beginning to see the body as it really is, and not as one might want or imagine it to be. Especially as an independently imagined entity—as though you, yourself, were somehow intellectually or mentally separated from the physical “bag-of-bones body” itself.

Moreover, no matter how well the body parts may usually function together to sustain life and even to provide momentary pleasures, they are still just body parts that have, through a process of evolution, come together in order to sustain life.

Using a simile, again, for the sake of comparison, the Buddha goes on to add that it is as if:

“A skilled butcher or his apprentice, having killed a cow, would sit at a crossroad cutting it up into pieces . . .”

Thus the monk or meditator learns to contemplate the body as though it were just made up of component parts.

Elsewhere, the Buddha says that even a king’s chariot is not a unity but just made up of its individual parts.

In the same sutta as above, the Buddha also reminds us that this body is composed not only of component parts, but that the parts are made up of combinations of “matter, liquid, heat, and gas.” And this being so, we should know that this sack-full-of-elements, in accordance with bio-chemical laws, contains an ever-changing process of the arising and ceasing of solidity, liquidity, burning energy, and gaseous aridity, and has no fixed or permanent existence.

Imagine solidity turning, through heat, into liquidity, and burning as energy, and turning into invisible gaseous aridity within your own body. Imagine your body as continually consuming itself.

The body is just a sack of elements, ever-changing, burning up internally as sources of nourishment, and ever being replaced by new bodily sources of energy.

And how about you? Do you assume that you are a “fixed unity to be nourished” called a “self to be satisfied,” rather than just a simple aggregation of component parts, made up of elements, which in turn nourish the body parts with energy just to keep them functioning? How do you see your own body?

If you have never thought this through before, perhaps it is time to begin.

References

Viriyang, Luang Phor. 1999. Meditation Instructor Course I. Bangkok: Willpower Institute (private printing of internal handout.)

Related features from BDG

The Mind Refining the Mind

Doing What Has to Be Done

Impermanence and Nothingness