Image courtesy of the Ministry of Culture, Nara Prefecture

Japanese culture maintains some of the most ancient extant forms of performance and ritual in the world, among them the well-known Noh and Kabuki. These forms have even older, pan-Asian influences and roots that extend to Mongolian exorcistic rituals; to geisha performances featuring the old dances mixed with the latest musical trends; and even to traveling freak shows, acrobats, jugglers, and comics. The oldest known agricultural rites involved irrigator-sorcerers who controlled the water for everyone’s benefit; these archaic practices, too, link directly to the ancient rite of Okina, preserved today within Noh theater. The impact and action of Okina is simple: a blessing for life, for food, and for peaceful continuity. This archaic blessing has never stopped in recorded history—our ancestors’ voices of goodwill and protection continue to resound as we begin 2022.

exhibiting archaic characteristics, such as a detached jaw

and real hair. Photo from Core of Culture

The White Old Man is an Asian archetype, of which Okina is an expression. He appears throughout China, Central Asia, the Himalayas, and South Asia. He is the oldest man, the most ancient ancestor, and he smiles as he performs the dance-prayer for prosperity, health, and peace accompanied by words that are not comprehensible today. These words come mostly in the form of a dialogue between three elemental deities who comprise a performance of the Okina rite: Senzai, Okina, and Sanbaso. Much like a priest or monk, the high-level Noh and Kyogen* actors allowed to perform Okina observe fasts and perform specific prayers in advance. Offering and drinking sake, they make an altar room for the Okina masks out of the usual green room for preparation.

Date unknown. Photo by SB Klein, UCI

Among Japanese performance forms, three lend themselves to understanding complex ancient transmissions and aggregations of dance forms over the millennia. These are the ceremonial dances of Bugaku, the ancient rite of blessing Okina, and the Shinto priestess’ miko dances. I’ve written on bugaku elsewhere for this journal: The Very Long Life of Bugaku.

The miko are elusive and very few Westerners have close contact with that esoteric and very old tradition. Dr. Elizabeth Tinsley of the University of California, Irvine, has lived with and practiced the miko traditions. Her experience is rare. Regarding Okina, quite a lot of specific information is recorded as far back as the 12th century, detailing transmissions going back to the 10th and even the eighth centuries, when certain pan-Asian traditions entered Japan through Korea—a cultural epoch resulting from the superabundance of cultural exchange during China’s Tang dynasty. Chinese traditions of dance, architecture, religion, and governing ethics had been arriving in Japan since the sixth century. Indigenous Japanese Shinto practices and shrines were the first port of religious adoption, and the site of entertainments such as Sangaku, Sarugaku, Okina, and Noh. Okina retains elements of Central Asian exorcism, Shinto, animism, agricultural rites, Buddhism, and the cultural cosmopolitanism of the Tang.

Image courtesy of the Ministry of Culture, Nara Prefecture.

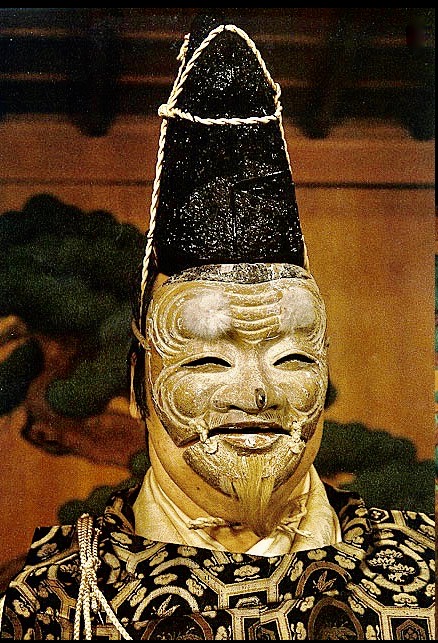

Today, Okina is kept alive within the repertory of Japanese Noh plays. It is, however, not a Noh play. It is an ancient rite performed by Noh and Kyogen actors. Two clear signs of antiquity appear in Okina masks, which are in two parts, with a detached jaw. The mask also has real hair affixed to it. These two attributes connect to a long history of ritual performances throughout Asia using a similar mask in a similar ancestral deity role.**

In the 13th century, Noh first appeared as Sarugaku Noh. Sarugaku is the Japanese term for traveling variety show-style entertainment imported from China in the eighth century, called Sangaku. This style of show included acrobats, martial artists, farce and parody, and comics in a fight. It had songs, dances, freak show elements, and superstitious spooky tales. It also had the White Old Man giving danced blessings and a dialogue with the deities.

By the 10th century, Sarugaku had become a distinct Japanese form, featuring dances, comics, short skits with dialogue, exorcistic dramas, and was increasingly incorporating elements from indigenous Japanese danced agricultural rites called Dengaku. Okina, Kyogen, and Noh derive from Sarugaku, which evolved from Sangaku, a pan-Asian variety show of traveling entertainments common in China since earliest times. Composer Ryuichi Sakamoto calls Okina “a multi-cultural symbiosis.”

From left to right: Senzai, Sanbaso, Okina.

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum, New York

Kyogen is Noh-style comedy directly evolved from Sarugaku. Noh became Noh after the child prodigy Sarugaku actor Fujiwaka was discovered by the Shogun Yoshimitsu. His tutelage of Fujiwaka resulted in Zen Buddhism and metaphysical aesthetics imbuing Noh with a transcendence distinguishing it, fundamentally, from Sarugaku. Fujiwaka became Zeami. Zeami’s father created Sarugaku Noh by adding ghost stories to reanimate famous figures; Zeami put this all into a poetic Buddhist metaphysical context. The sparse dialogue structure in Noh harks back to Sarugaku as well. The incomprehensible conversation among deities in Okina is a divine prototype.

According to Zeami, the 13th century founder of Noh, in the 10th century the patriarch of Sarugaku, Hada no Kokatsu, created 66 Sarugaku dances for the peace and prosperity of the Emperor Murakami’s reign. These 66 dances were maintained with authenticity by Zeami’s contemporary Hada no Udiyasu. Udiyasu selected three of these 66 dances and created a three-dance set of most auspicious dances. He called this three-dance set Shiki-sanban, another name for Okina. Zeami saw the Sarugaku Shiki-sanban’s three dances, including Okina and Sanbaso.

The third deity dance he saw is now performed by the deity Senzai. Okina’s three deities offering dance-prayers of blessing for peace and prosperity is the survival of a very ancient rite. In Noh theater, Okina is performed for auspicious occasions, such as New Year. It is not a Noh play. It precedes all the performances, offered first, as a rite, conducted by select Noh and Kyogen actors. Okina is a conduit to the seed essence of their art, older than their art, symbolizing, representing and expressing ancestral belief and goodwill.

Toriyama Seiken. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum, New York

Two Noh actors and a Kyogen actor enter the stage, unmasked. Only in Okina is the mask put on the actor’s face onstage. The act of making the human into a deity is an essential part of the rite. Both the Okina and Sanbaso masks—White Old Man and Black Old Man, respectively—are put on and taken off onstage. The third deity carries the masks onto the stage as the three enter, and has a dialogue with each of the other two deities once they have donned their masks. This dialogue is written in divine language that cannot be understood. Some scholars consider it to be terribly corrupted Tibetan. Okina’s dance is ceremonial and dignified. Sanbaso’s dance is robust and moves over the land. Both are smiling, both are as old as you can imagine. The oldest voice is a blessing and encouragement for today.

Now, Okina returns another year to wish us all peace and abundance, having come from far across space and even farther across time. Wishing you a happy New Year.

* A Noh-style form of comedy.

** Dance as Knowledge, Part Two: Wu Nuo (BDG)

See more

Related features from BDG

The Very Long Life of Bugaku

Dance as Knowledge, Part Two: Wu Nuo

reading this was a great way to enter the new year