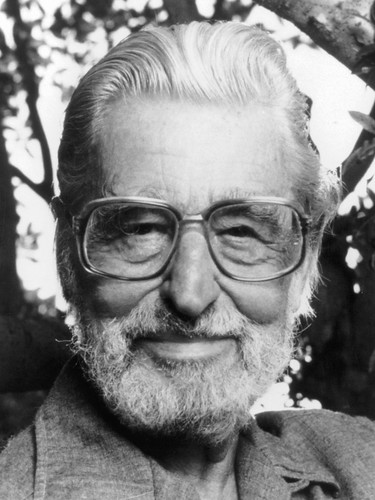

Of the all the editorials that have been written about Trump’s proposed border wall between the United States and Mexico, none in my humble opinion rivals the 1984 satirical tale penned by Dr. Seuss in The Butter Battle Book.

I’m not saying Dr. Seuss’s story offers the most subtle or sophisticated analysis, but then again I don’t really think subtlety or sophistication are called for on this particular issue. As Albert Einstein probably never said, “If you can’t explain it to a six year old, you don’t understand it yourself.”

Although Seuss is still best known for wacky classics such as The Cat in the Hat and Green Eggs and Ham, you don’t have to be a lit. prof. to have noticed what the legendary graphic artist Art Spiegleman pointed out: there are “political messages . . . embedded within the sugar pill of Dr. Seuss’s signature zaniness.” (Minear, 2001, iv)

In fact, there seem to be so many of these messages that when Michael Kazin, the long-time editor of Dissent magazine, drew up a list of the most influential American progressives of the 20th century—a list, it’s worth mentioning, that included Martin Luther King, Jr., Emma Goldman, César Chávez, John Dewey, W. E. B. Du Bois, Michael Harrington, and Betty Friedan—he concluded that “for broad and continuing appeal among both young and old, one individual stands apart: Dr. Seuss.”*

Seussian politics

Seuss certainly wasn’t afraid to step into the political ring.

As Richard Minear illustrates in Dr. Seuss Goes to War, for a two-year period during World War II Seuss penned hundreds of cartoons that made explicit the political views that he would later take underground in his fiction. Interestingly enough, during this time he railed against many of the same tendencies that have reared their ugly heads again in recent years: isolationism, racism, anti-Semitismand, long before it became official American policy, what he called “America-firstism.”

In the spring of 1974 as the Watergate scandal neared its climax, on a dare from the newspaper columnist Art Buchwald, Dr. Seuss also made a highly political re-write of his recently released children’s book, Marvin K. Mooney Will You Please Go Now!

By simply replacing each mention of Marvin K. Mooney with the name Richard M. Nixon, he made his story read like this:

Richard M. Nixon will you please go now!

The time has come

The time is now.

You can go on stilts.

You can go by fish.

You can go in a Crunk-Car if you wish.

Richard M. Nixon, I don’t care how.

Richard M. Nixon! Will you please GO NOW!

Nine days after Seuss’s re-write was nationally syndicated, Nixon announced his resignation and the good doctor took full credit, writing to Buchwald: “We sure got him didn’t we? We should have collaborated sooner.” (Morgan and Morgan, 273).

Dr. Seuss for current use

If you ask me, the political themes in Seuss’s stories are more relevant now than they were at the time he wrote them.

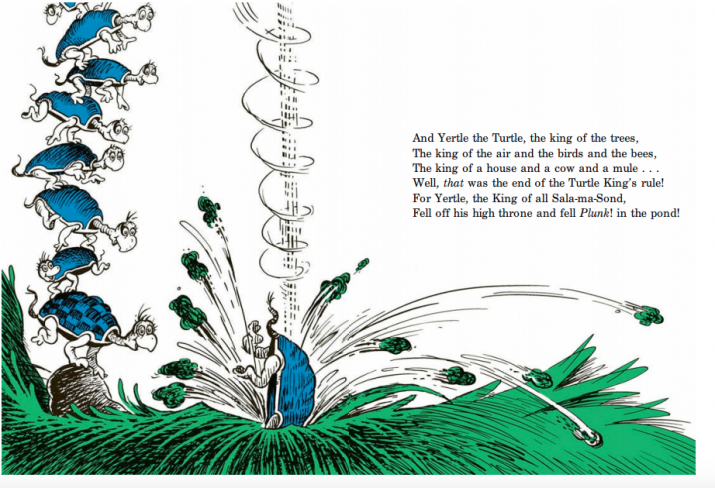

For instance, it’s hard to read Yertle the Turtle these days without seeing Trump as the tyrannical turtle who builds himself a Trump Tower-like throne out of his fellow turtles so that he can appropriate more and more of the commons. It’s also hard to imagine that some hard-working turtles like Mack, the lowest turtle on the turtle-pole, won’t finally topple President Yertle from power in an insurrection that will seem as natural and inevitable as Mack’s rebellious burp.

It’s also pretty tricky to read The Lorax now without seeing Trump as the entrepreneurial Once-ler who is carelessly decimating a fragile ecosystem of Truffula trees, brown Bar-ba-loots and climate-change activists like the Lorax himself in his relentless quest to “bigger” the profits he and his cronies make off their useless Thneeds.

But, as I mentioned, at this particular moment in time—with all the talk of the border wall and the summits with Kim Jong-Un—the Seuss story that seems the most prescient of them all is also his most controversial: The Butter Battle Book.

The Butter Battle Book

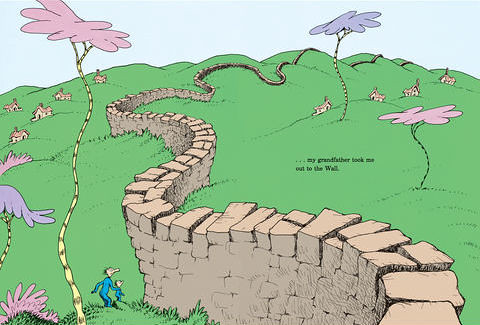

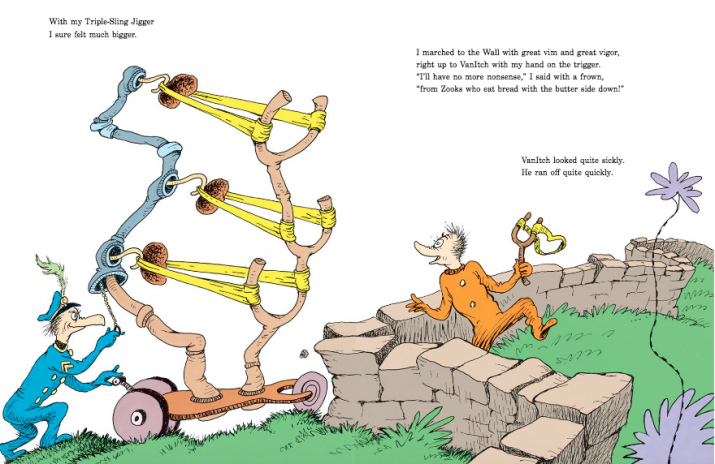

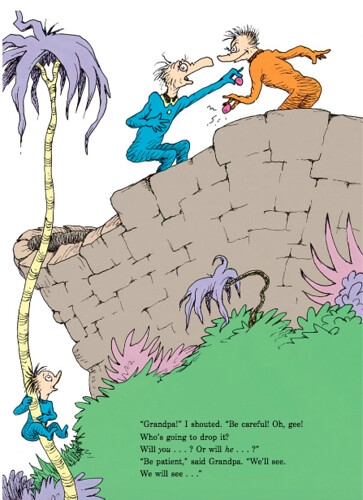

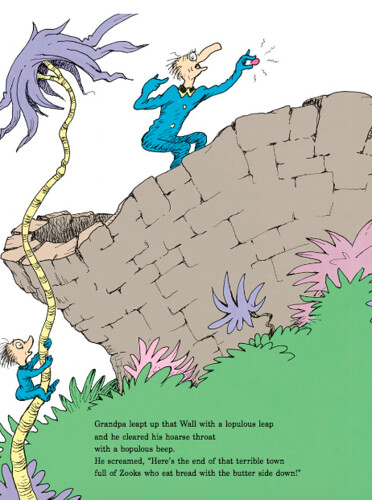

Published in 1984, The Butter Battle Book is the story of two strikingly similar societies of bird-like creatures who build a wall between one another and engage in an arms race that ends in a nuclear standoff.

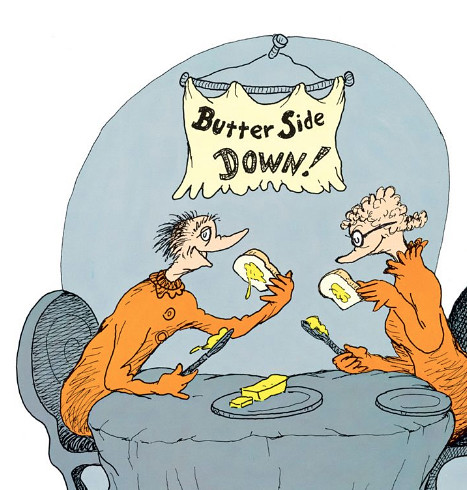

What leads the Yooks and the Zooks to construct the wall and then become embroiled in an arms race is typically absurdist Seuss fare: while the Yooks butter their bread butter-side up, the Zooks butter their bread butter-side down.

Given the Cold War context Seuss was writing in, it seems pretty clear that the Yooks were primarily meant to symbolize American supporters of the militaristic Reagan administration, while the Zooks were intended to represent Soviet supporters of the militaristic Andropov and Chernenko administrations.** It also seems pretty clear that the wall separating the Yooks and Zooks originally evoked the Berlin Wall.

But what’s equally obvious is Seuss-fan Tim Burton’s observation: “Like any good folktale, Dr. Seuss’s stories are timeless and they have cultural and sociological meaning that will always hold true.” (Fraga, p.169) After all, why would Seuss have chosen to write in allegories if he didn’t want his fiction to speak to situations other than the obvious ones he was writing them for? Like, for example, Trump’s border wall.

So let’s take the wall in Seuss’s story to symbolize the proposed border wall between the US and Mexico, and let’s take the Yooks as symbols of Trump supporters of the border wall, and the Zooks as symbols of the Mexicans on the other side of that wall. What can Seuss’s story tell us about the wall?

There are, I think, at least five main take-aways.

1) Similarities trump differences

Regardless of who we take the Yooks and Zooks to symbolize, what leads to the construction of the wall in the first place remains the same: which side of our bread we choose to butter. Which is also obviously symbolic. But of what?

The answer seems clear: cultural differences.

Seuss’s decision to depict the differences between the Yooks and the Zooks as something as arbitrary and absurd as the side of their bread they choose to butter is the key element in his critique. But it’s also what caused the story to be criticized for promoting “moral equivalence” by some conservative readers.***

Were the differences between American-style free-market capitalism and Soviet-style socialism during the Cold War (or are the differences between American culture and Mexican now) as trivial as the difference between what side of our bread we choose to butter?

At first sight, the answer seems obvious: of course not.

But that’s the whole point of the story. While acknowledging cultural differences, it deliberately minimizes their significance by setting them against the backdrop of overwhelming similarities. Of course, there are important differences between American and Mexican cultures today, just as there were important differences between American and Soviet cultures during the Cold War. But the story encourages us to stop pinch-zooming on the differences and instead pinch out so we can see the commonalities.

The Yooks and the Zooks have almost identical names; they look almost identical; they dress almost identically; they live in almost identical houses within an almost identical landscape; they have an identical fondness for eating buttered bread. And so on and so forth.

In other words, when we take a Google Earth view of things and consider all that the people of different nations have in common, it doesn’t really matter what arbitrary differences are seized upon to justify the building of walls: all such differences are as trite and absurd as the side of our bread we choose to butter.

As Seuss himself said, “What I was trying to say was that the Yooks and the Zooks were intrinsically the same. The more I made them different, the more I was defeating the story.”

Ironically, an empathic appreciation of these similarities is precisely what is obscured by the wall in this story, and the many walls in the world outside it. And unfortunately (and fortunately!) several research studies have shown that training in perspective-taking and empathy are precisely the skills needed to reduce generalized prejudice. For instance, Nic Hooper and his colleagues have shown that a very simple perspective-taking exercise (i.e. an exercise that trains one to adopt another’s viewpoint) significantly reduces generalized prejudice.

But walls create mental and emotional barriers to empathy that divide people into easily defined in-groups and out-groups, and exaggerate differences. What’s more, by preventing people from engaging in everyday, face-to-face interactions, they also prevent people from directly experiencing the many things they have in common with those who are different from them.

Finally, by excluding other perspectives walls subtract the human element from conflicts, thereby increasing prejudice and violence. All of which results in a vicious cycle: as a wall reduces empathy, it exacerbates exclusion and escalates conflict, which in turn further impoverish empathy while continually escalating conflict and exclusion. Which is probably why Seuss’s wall grows higher and higher over the course of his story.

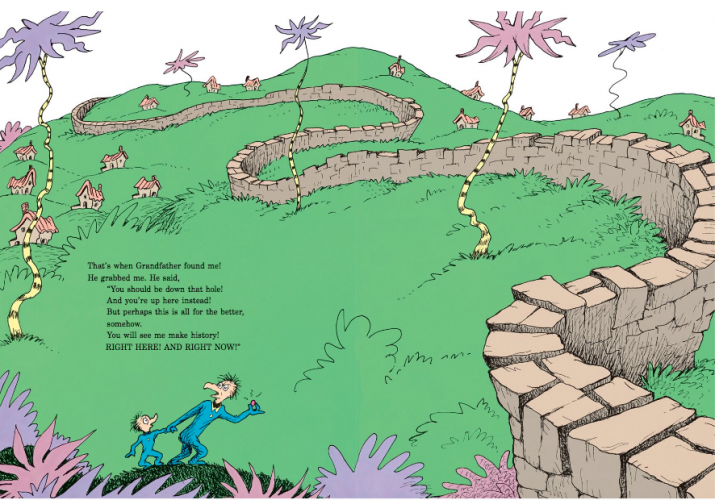

2) A “big beautiful wall” bolsters support for behind-the-scenes political goals

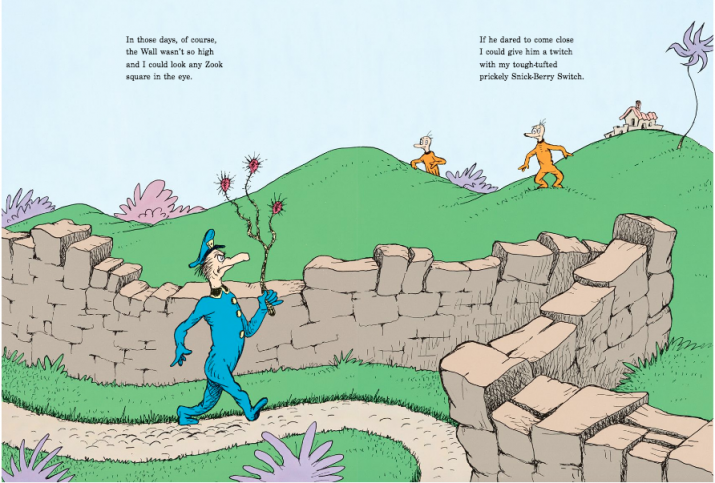

The Yooks’ “big beautiful wall” is also conspicuously plastered with propaganda. There is, for instance, a prominently displayed banner on the Yook side that proclaims in bold black letters: “Yooks are not Zooks. Keep Your Butter Side Up!”

The poster not only reminds Yook society of its irreconcilable differences with the Zooks but also contributes to the kind of internalized opposition that has been drilled into all Yooks, including Grandpa, from a young age.

This ideology of national moral superiority and contempt for cultural differences pervades every visible aspect of Yook society, relentlessly reinforcing prejudice. As Grandpa approaches the wall with a cannon-like “Kick-a-Poo-Kid” to bomb the Zooks, a crowd of Yooks enthusiastically egg him on, cheering, “Fight! Fight for Butter Side Up! Do or Die!”

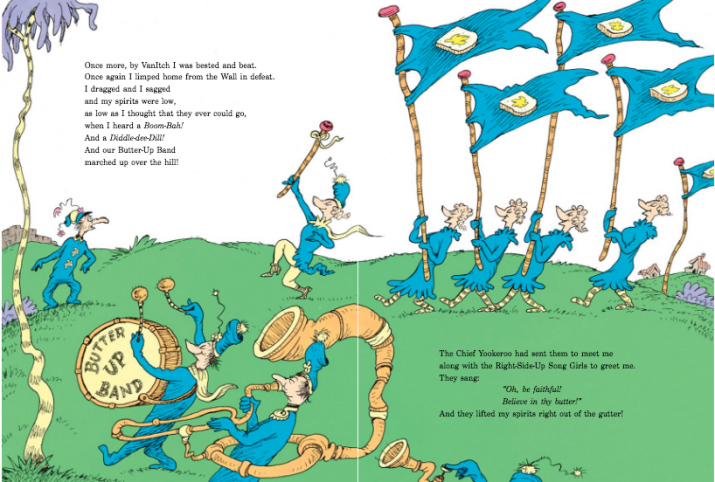

When Grandpa returns from the wall in defeat after being outmatched by the Zooks, he is met by the music of the “Butter Up Band” and the “Right-Side-Up Song Girls” who proudly fly flags depicting butter-side up toast, while singing “Oh, be faithful! Believe in thy butter!” The emphasis on faith has obvious religious connotations, but here again they are applied to the absurd and arbitrary symbol of buttered bread.

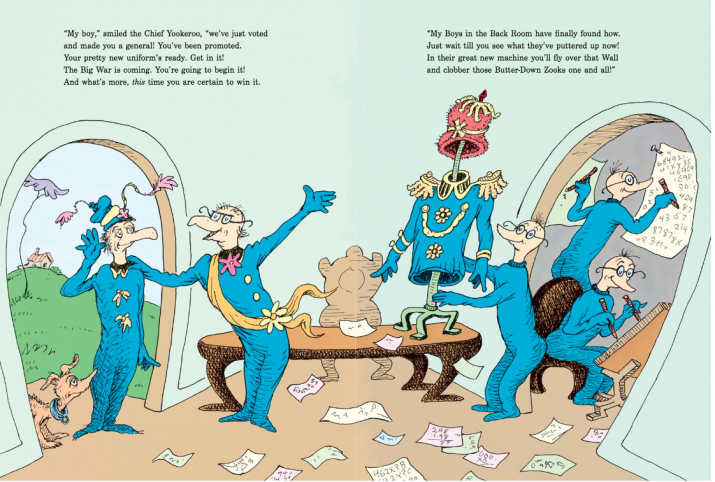

When Grandpa finally consults the office of the Chief Yookeroo, we discover the source of all this propaganda. Emblazoned on a coat of arms above the president’s office desk is a piece of white bread smeared with bright yellow butter, butter-side-up.

But why, according to Seuss, is the office of the Chief Yookeroo engaging in all of this social conditioning? Because bigotry and an old-fashioned good-versus-evil narrative are extraordinarily helpful in drumming up the kind of nationalistic fervor that bolsters support for behind-the-scenes political goals.

Duh.

In the story, these goals are mainly related to the weapons industry. During each of his visits to the Chief Yookeroo, Grandpa receives a more expensive and advanced weapon with which to defend the border. Each is produced by the bespectacled “Boys in the Back Room,” a cabal of weapons manufacturers whose office literally adjoins the Chief Yookeroo’s.

In other words, Grandpa (a member of the military) is given new weapons by a president (the oval office), which is produced by the Boys in the Back Room (the weapons industry). Together, they form a three-sided relationship that is sometimes referred to as the “iron triangle” of the military-industrial-congressional complex.

Of course, the situation in the US today is a bit different. The Boys in the Backroom are not only weapons manufacturers but corporate oligarchs quietly privatizing what is left of the commons. The main political problems of the day have also changed. Today, they include widespread suspicions of collusion with Russian agents to influence the election results in the Republican’s favor, the opioid crisis, terror, crime, and the economic decline of the working and middle classes.

But the function of the wall remains the same—it attributes all of these political problems to a demonized other or them. A wall makes it seem like drug-smuggling from Mexico is the big problem. But is heroin from Mexico responsible for the American opioid crisis? Or are economic destitution, social anomie, poor healthcare, pill mills, and the over-prescription of painkillers the real culprits?

A wall makes it seem like the crime and terror problems are the fault of the “tough hombres” supposedly flooding over the southern border. But is this accurate? New immigrant populations are not only disproportionately law-abiding, but economically and educationally aspirational. Aren’t the real problems decades of flawed Middle East policy and homegrown, mostly white young men with easy access to guns?

A wall makes it seem like undocumented, job-stealing immigrants are responsible for the economic decline of the middle and working classes. But don’t Mexican immigrants actually supply low-wage labor in agriculture, construction, cleaning, maintenance and so on? The precarious economic predicament of the middle and working classes seems more closely related to low wages, broken unions, unfair access to education, massive debt, and soaring housing and healthcare costs.

But a “big beautiful wall” tells a much simpler story.

On the right side of the wall we have the safe, law-abiding, hardworking citizens of the USA. And on the wrong side, we have the dangerous, criminal parasites who are to blame for all the problems on the right side.

This is the story that propelled Trump to power. It was the cause of the longest government shutdown in US history. And it’s the reason we’re going to keep hearing about the wall for a long time to come.

3) Guilty but not to blame

Grandpa’s visceral response when he first mentions the Yooks’ practice of bread-buttering is arguably the most important moment in the entire story. To Grandpa, the Yooks’ style of bread-buttering is not only “horribly terrible,” but a sign that all Yooks have “kinks in their souls.” Everything else in the story flows from this knee-jerk reaction.

It’s the reason they build the wall. It’s the reason Grandpa joins the border patrol. It’s the reason he ultimately attempts to exterminate the supposed source of his disgust. And it is, I imagine, something akin to what many Trump supporters felt when they first saw Trump coming down that escalator ranting that Mexican immigrants are “drug dealers, criminals, rapists.”

Grandpa has a prejudicial response, there’s no doubt about that. In fact, his beliefs are a classic example of “the fundamental attribution error” (the tendency to judge the behavior of others based on supposedly dispositional characteristics, such as genes or personality, instead of their history and circumstances). This, in turn, is the central process that underlies generalized prejudice (Hooper et al, 2015; Levin et. al, 2016).

So Seuss makes it clear that Grandpa is guilty. But he also seems to imply that Grandpa is not exactly to blame. After all, as we have seen, Grandpa’s prejudicial associations have been relentlessly hammered into him by the wider Yook culture, and that culture is inside him, just as our cultures are inside each of us.

As the main implicit bias tests (the IRAP and IAT) reliably show, within a few milliseconds of seeing someone we judge them, often in a prejudiced way. Based on gender, race, ethnicity, religion, class, sexuality, age, disability, or nationality, we judge and we stereotype. All of us. Women judge women in a stereotyped way; overweight people judge obese people in a stereotyped way, and on and on it seems to go.

Why?

Steven C. Hayes provides one answer: “Because you grew up in a culture that trained the prejudiced judgements over and over and over.” (Hayes 2016) To different degrees, we all have the common stereotypes drilled into our heads, and there’s some pretty depressing evidence that shows that once we learn them, they never really disappear. (Devine 1989) There’s also some inconvenient evidence that when we encounter new information that conflicts with older stereotypes, we tend to resist that information. (Moxon, Keenan, & Hine 1993; Watt, Keenana, Barnes & Carins 1991) As if that weren’t dispiriting enough, we seem to remember stereotypes better than new information (Bodenhausen 1988) and often interpret ambiguous information in a way that confirms our existing stereotypes. (Duncan 1976)

Some social scientists have accounted for the tenacity of stereotypes by suggesting that they reduce the burden of problem-solving and understanding a complex social environment. (Macrae, Milne, & Bodenhausen 1994; Banah & Greenwald 2013)

Others have suggested that they are a product of natural selection that supported early humans in assessing the relative safety or danger of strangers.***** Bias, they hypothesize, was the mechanism that helped us decide who or what was a threat.

For instance, in the bestselling book Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People, Mahzarin Banaji and Anthony Greewald cite research showing that by three months of age, babies gaze longer at a face from their own racial group than at one from a less familiar racial group. Commenting on this research, they write, “Human babies appear to enter the world ‘prepared’ to form preferences, including complex social ones. And familiarity always seems to be the basis for the preferences they express.” (Banah & Greenwald 128) This seems to have survival value because it aligns the child with those who are like it or are more likely to offer safety, a clear sign, according to the authors, that “even in these early months babies do not occupy socially neutral space.” (Banah & Greenwald 128)

In short, as unfortunate and embarrassing as it may be, whether we like it or not, there seems to be a little bit of Grandpa in all of us. Even those of us who are the most self-righteous. Like the grandson or even arguably Grandpa in Seuss’s tale, we come by our prejudices honestly, through no fault of our own. Nevertheless, as Steven C. Hayes puts it: “A war on prejudice could certainly safely start with the person one sees when brushing one’s teeth. We could stop running from our own objectification and dehumanization of others, and admit the presence of these everyday cognitive processes.” (Hayes, et al, 2002, 300)

4) Avoid avoidance

But The Butter Battle Book is also a cautionary tale about the ludicrous, apocalyptic lengths to which some people will go to avoid simply allowing their discomfort with difference. The guns, the bombs, the wall—in The Butter Battle Book, they’re all built because Grandpa simply can’t tolerate the disagreeable feelings of fear and distrust that whelm up inside him when he thinks of those whose cultural practices differ from his own.

Rather than open up to that discomfort and unhook from his prejudicial thoughts, he literally tries to wall himself off from his reactions and eliminate those whom he takes to be the source of his disgust. This is Grandpa’s version of aversion.

And it doesn’t work. In the fictional world of Dr. Seuss, it never does.

Seuss’s magnificent oeuvre is, among many other things, an encyclopedia of disastrous attempts to avoid unwanted thoughts and unpleasant emotions. In fact, one of the most consistent themes in his fiction can be summed up in two succinct words: avoid avoidance.

For instance, after the narrator of I Had Trouble in Getting to Solla Sollew encounters some adversity, he tries to do away with all feelings of distress by setting off in search of a utopia called Solla Sollew, where there are no troubles at all, or at least very few. Needless to say, he never gets inside Solla Sollew. Instead, he gets himself into a lot more trouble than he had before he set off in search of this illusion.

After the narrator of Oh, the Places You’ll Go falls into a slump, one of the ways he tries to “un-slump” himself is by killing time in “the waiting place.” Not only does this deepen and prolong his slump, it prevents him from getting where he wants to go.

In The Sneetches, the plain-bellied Sneetches who have no stars upon thars try to cope with their status-anxiety and hurt feelings by spending vast sums of money to have stars surgically added to their bellies, and then removed, added, removed, and added again. It gets them nowhere and costs them every cent they own.

In Gertrude McFuzz, a plain-looking bird who has only one shabby tail-feather feels jealous and inadequate when she compares herself to the lavishly-feathered Lolla Lee Lou. In an attempt to eliminate these feelings, Gertrude overdoses on pill-berries and winds up growing so many tail-feathers she can barely move.

The list goes on.

But no other story in the Dr. Seuss canon comes close to The Butter Battle Book in depicting the dire negative consequences that can come of emotional avoidance. In their dogged attempts to avoid their mutual feelings of fear and distrust the Yooks and Zooks not only build a wall and engage in chemical warfare, but they push one another to brink of mutual nuclear extermination.

As far as I can see, Dr. Seuss never actually implies that experiential avoidance is bad or wrong. He simply observes that it doesn’t work. And that it makes things worse. In some cases, much much worse.

5) Mindfulness as an antidote to prejudice

So what’s the alternative?

To win power, obviously. To get the office of the Chief Yookeroo and other offices like it that bestow such extraordinary powers of influence.

But at the level of the individual? If Grandpa hadn’t gotten entangled in his prejudicial thoughts (i.e. taken them to be the truth) and tried to eliminate his prejudicial feelings (i.e. by walling himself off from the Zooks and then trying to exterminate them), what might he have done? Several research studies have shown that mindfulness-based approaches, like acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), can dramatically reduce prejudice. (Hayes et al 2004; Lillis & Hayes 2007; Masuda et al 2007)

Michael Levin and his colleagues summarize the main mindfulness-based interventions that all of these successful studies implement: they “encourage an alternative approach to relating to prejudiced thoughts and feelings in which individuals take an open, aware, and compassionate stance toward their prejudice reactions and are taught to simply notice them for what they are (i.e. a thought or feeling) without giving into, agreeing with, acting on, judging, or fighting them.” (Levin et al, 2016, p.189)

In other words, if Grandpa were to have tried this approach, he might have simply noticed that his mind was handing him the thought that the Zooks’ bread-buttering practice meant that they were “horribly terrible” people with “kinks in their souls.”

And from a quiet distance, with a lot of curiosity, he might have simply watched that thought and seen it for what it is: just a thought, an unfortunate but impersonal product of social conditioning and natural selection. Not the truth and not his fault. But something he is certainly response-able for; in other words, something to which he is able to respond in the way he chooses.

So he might have checked in with himself to see how he wished to respond. And he might have reminded himself of his heart’s deepest desires for how he wanted to be and behave as a human being in general, and more specifically as a grandfather in this situation, with his grandson looking on.

And then, as disagreeable as it might have seemed, rather than trying to eliminate or surrender to his feelings of fear and distrust, he might have summoned some curiosity and self-compassion, and simply allowed these feelings, perhaps asking himself every once in a while: “What is this?” and “Can this be allowed?”

And perhaps, for a moment, he might have also slipped out from behind his own eyes and looked at the world from behind Zook eyes, and then, while he was there, taken the elevator first down and then back through some of the possible incidents and accidents that led them to butter their bread butter-side down in the first place.

And then, rather than getting hijacked by his conditioning, he might have acted in alignment with what he saw and what he valued.

Doing better

Just a few weeks before he died, Dr. Seuss was asked whether, after all the books he’d written, he had left anything unsaid. (Morgan and Morgan 1996, 286–87)

He cocked his head and said, “Let me think about it.”

Two days later, on a sheet of yellow copy paper, he wrote the following sentence: “The best slogan I can think of to leave with the kids of the USA would be: We can . . . and we’ve got to . . . do better than this.”

Then he crossed out three words: the kids of.

As his widow Audrey Geisel said of the note, “He wasn’t talking to children. He was talking to humanity.”

* The Seussian Left (Dissent)

** During the first half of the 1980s Cold War, tensions were rising and the threat of nuclear annihilation seemed terrifyingly real. In 1984, the year the book was published, President Reagan was investing heavily in nuclear weapons as well as the infamous strategic defense initiative popularly known as “Star Wars.” In the previous year, nuclear war had also been beamed into American living rooms via ABC’s broadcast of The Day After, a widely watched movie depicting America after nuclear attack.

*** For instance, in a 2004 article, John J. Miller refers to the The Butter Battle Book as a “perfect emblem of the moral equivalence that neutered so many liberals during the Cold War.” Writing in The National Review in 2012, Ross Douthat criticizes the premise of the story for being “morally dubious” mainly because of its “naïve moral equivalence.”

**** Hooper, Nic et. al. “Perspective taking reduces the fundamental attribution error.” Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. Volume 4, Issue 2, April 2015, pp 69–72.

***** David Myers explains in The Powers and Perils of Intuition, “We fear what our ancestral history has prepared us to fear . . . snakes, spiders, and humans from outside our tribe.” Myers theorizes that “risk intuition” was a survival mechanism that allowed early humans to quickly distinguish a tribe member from a potentially threatening outsider.

References

Banaji, Mahzarin R. and Anthony G. Greenwald (2013). Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People. Delacorte Press.

Bodenhausen, G. V. 1988. “Stereotypic biases in social decision making and memory: Testing process models of stereotype use.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 726–37.

Devine, P. G. 1989. “Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 5–18.

Duncan, B. L. 1976. “Differential social perception and attribution of intergroup violence: Testing the lower limits of stereotyping of Blacks.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 590–98.

Fraga, Kristian. 2005. Tim Burton Interviews. University Press of Mississippi.

Hayes, S.C., Niccolls, R., Masuda A., Rye, A.K. 2002. “Prejudice, terrorism and behavior therapy.” Cognitive and behavioral practice 9, 296–301.

Hayes, S. C., Bissett, R., Roget, N., Padilla, M., Kohlenberg, B., Fisher, G., et al. 2004. “The impact of acceptance and commitment training and multicultural training on the stigmatizing attitudes and professional burnout of substance abuse counselors.” Behavior Therapy, 35, 821–35.

Lillis, J., & Hayes, S. C. 2007. “Applying acceptance, mindfulness, and values to the reduction of prejudice—A pilot study.” Behavior Modification, 31, 389–411.

Macrae, C. N., Milne, A. B., & Bodenhausen, G. V. 1994. “Stereotypes as energy-saving devices: A peek inside the cognitive toolbox.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 37–47.

Moxon, P. D., Keenan, M., & Hine, L. 1993. “Gender-role stereotyping and stimulus equivalence.” The Psychological Record, 43, 381–94.

Hayes, Steven C. “Overwhelmed: why Trump is happening now.” Psychology Today. 3 April 2016.

Masuda, A., Hayes, S. C., Fletcher, L. B., Seignourel, P. J., Bunting, K., Herbst, S. A., et al. 2007. “The impact of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy versus education on stigma toward people with psychological disorders.” Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2764–72.

Minear, Richard. 2001. Dr. Seuss Goes to War: The World War II Editorial Cartoons of Theodor Seuss Geisel. New York: The New Press.

Morgan, Judith and Neil Morgan. 1996. Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: A Biography. Boston, MA: Da Capo Press.

Watt, A., Keenan, M., Barnes, D., & Cairns, E. 1991. “Social categorization and stimulus equivalence.” The Psychological Record, 41, 33–50.

1. This story was about the Cold War 2. All of your “similarities” are extremely vague 3. Suess died in 1991, the first official mention of the border occurred in around 2015