Treacherous waters

At four o’clock in the morning of 5 February 1912, 13-year-old René Magritte (who in later life would become one of the most famous surrealist painters of the 20th century) was startled from his sleep. His youngest brother, who slept upstairs in the same room as their mother Regina, had woken up in the middle of the night and realized he was alone. The whole family began searching the house in vain for Regina. René’s father, Leopold, must have been especially puzzled by her disappearance since Regina had recently fallen into a severe depression and it was his custom, during these episodes, to lock her inside her bedroom at night. Then they noticed traces of footsteps on the threshold of the front door and on the pavement outside. René Magritte later recalled that they followed the footsteps to a bridge on the nearby River Sambre, where the footsteps disappeared. Two weeks later, his mother’s drowned body was fished out of the river, her face covered by her nightgown. She had found the key to the bedroom, unlocked herself, and thrown herself into the river.

Almost 50 years later, when René Magritte was asked by a journalist how his mother’s suicide had affected him, he admitted that “these are things that one does not forget. Yes, that marked me.” Yet he denied that her death had had any lasting influence on him. “It was a shock,” he said, “but I don’t believe in psychology any more than I believe in will power. Psychology doesn’t interest me. It tries to explain a mystery. The only mystery is the world.” (Scutenaire 1982, 67–68)

Nevertheless, the image of his mother’s death recurs in many of his paintings, perhaps most notably in The Musings of the Solitary Walker (Les Reveries du Promeneur Solitaire) (1926), which depicts a man wearing Magritte’s signature bowler hat walking next to the very river where his mother drowned herself, with the bridge from which she threw herself in plain view in front of him and the image of a naked female corpse behind him.

From renemagritte.org

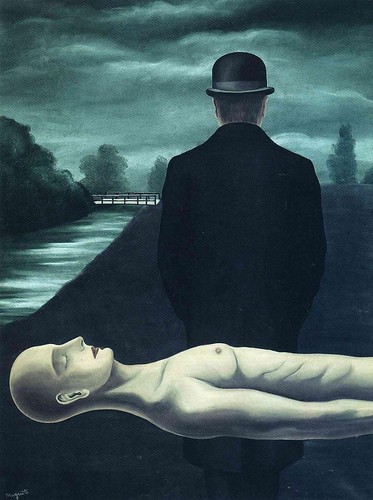

What’s more, although nobody knows for sure whether Magritte had heard that his mother’s body was found with her nightdress covering her face, given that shrouded faces and bodies became a recurring motif in many of his later paintings, it seems safe to assume that he did. In his somber painting The Invention of Life (1928), for example, we see a female figure that bears a very strong resemblance to his mother standing next to a figure shrouded in grey fabric.

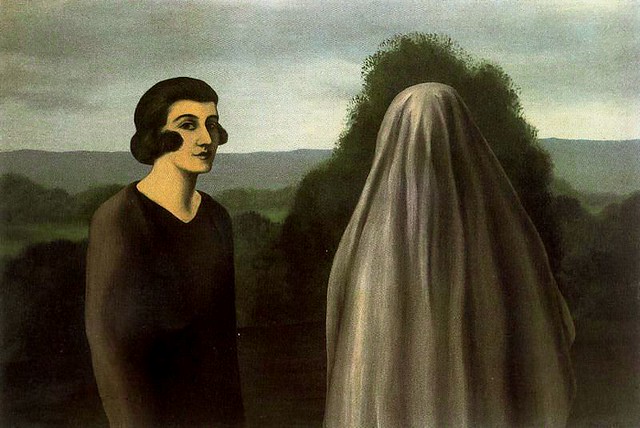

The same year he also painted two canvases entitled The Lovers which also feature figures shrouded in fabric:

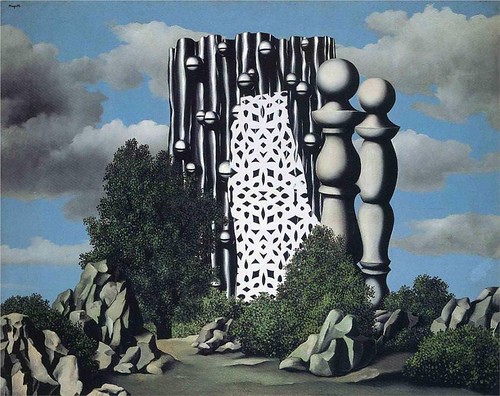

Moreover, when viewed through a biographical lens, his painting The Invention of Geometry (1937) (which was originally titled Maternity) might also be taken to suggest that from a young age Magritte may have felt like a parentified child who had to figuratively carry his mother in a relationship where the usual parent-child roles were reversed.

At the very least, it seems safe to assume that the image of his mother’s lifeless body continued to resurface in Magritte’s mind from time to time over the course of his life.

With this in mind, it also seems clear that many of Magritte’s most famous paintings are, among other things, ways of managing this difficult experience. While most of us are lucky enough not to have traumatic memories, almost all of us have a memory or two that causes us some discomfort: that attempted kiss that was rejected, that moment of public embarrassment, those hurtful words spoken in the heat of anger. Might Magritte have something to teach all of us about how to respond to the disagreeable, unpleasant, or even traumatic mental images that can arise in our minds?

The treachery of images

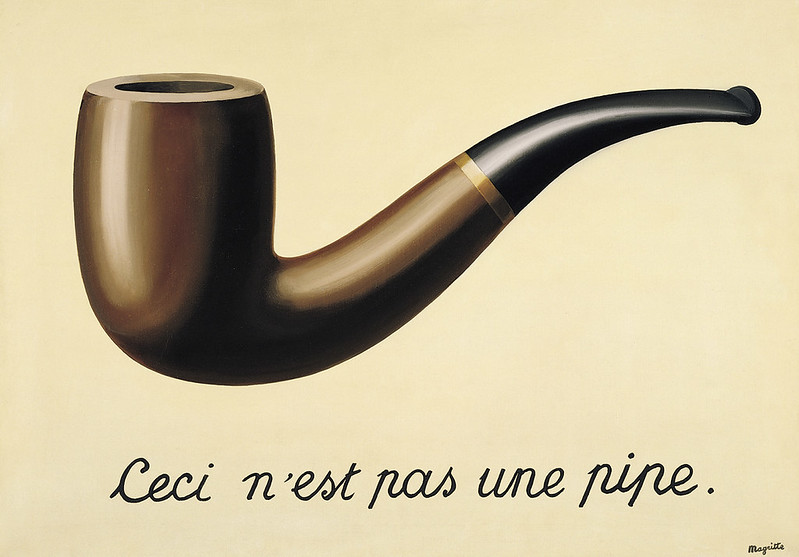

Throughout his adult life, Magritte remained fascinated with the way images bewitch us into believing that they are the things they refer to. Here, for example, is one of his most famous paintings, completed just a few months after the masked paintings included above.

There are, of course, many things that can be said about this iconic painting, which is one of the most famous of the 20th century, but perhaps the simplest and most banal interpretation is, practically speaking, the most helpful: if we take the words in the painting at face value (“This is not a pipe”) then at the simplest level the painting may be understood as an invitation to acknowledge that the image of a pipe is not an actual pipe; it is just what it is (i.e. an image) and not what it refers to (i.e. a real pipe).

As Magritte himself pointed out in a cartoon he penned just a year after this painting, “Everything tends to suggest that there is little connection between an object and that which represents it.” (Magritte 1929, 26)

While responding to the image of a pipe as though it were an actual pipe does not seem anywhere near as treacherous as the dramatic title of his iconic painting suggests (i.e. The Treachery of Images), there are other mental images that could be treacherous indeed, for instance the image of one’s mother’s drowned body or any other negative image that might keep resurfacing in our minds.

Viewed in this way, the painting might be understood as a sort of aide-memoire that Magritte used to remind himself (and us) that just as a mental representation of a pipe is not an actual pipe, so the mental representation of one’s mother’s shrouded corpse is not actually one’s mother’s shrouded corpse. In other words, working with less treacherous images, like pipes, might be viewed as a sort of practice ground for working with more treacherous images, like that of one’s mother’s lifeless body.

By remaining aware of this crucial distinction between mental representations of events and the events themselves, one might be spared from having to relive and re-experience the emotional charge and physical shocks associated with the disagreeable or outright traumatic images arising in the mind. If one allows oneself to be tricked by these treacherous images, on the other hand, one might relive everything one felt then (e.g. the intense shock and grief the young Magritte must have felt when they discovered his mother).

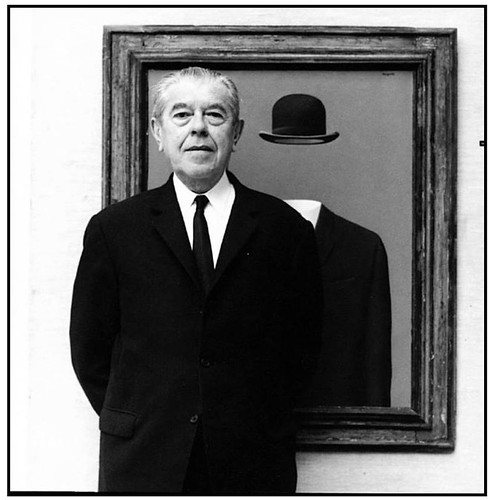

1967. From wikipedia.org

Magritte himself once said, “As for the mystery and enigma in my painting, I would say that it is the best proof of my break with the absurd mental habits that generally take the place of an authentic feeling of existence.” (Bennett-Goleman 2001, 130). One of the many “absurd mental habits” he may be referring to here is precisely the habit of taking the images that arise in our minds literally. This “absurd mental habit” takes the “place of an authentic feeling of existence” because it would have us relate to the dead, static images in the graveyards of memory, rather than the vital and “authentic” mystery of the world.

Liberating us from “absurd mental habits” and restoring “an authentic feeling of existence” was precisely Magritte’s project as a painter. As he said, “I want to breathe new life into the way we look at the ordinary things around us. But how should one look? Like a child, the first time it encounters a reality outside of itself. I live in the same state of innocence as the child who believes he can reach out from his cot and grasp a bird in the sky” (Magritte 2016, 122)

Perhaps this way of looking at the ordinary things around us is precisely what becomes available when we learn not to take treacherous images literally. Only then can we see the ordinary things around us not through the filter of our habitual, preconditioned associations, but anew, through fresh eyes, as if for the first or last time, with a sense of wonder at their presence, their mystery, and strangeness.

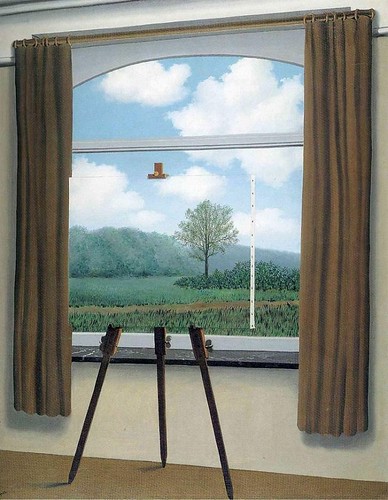

Yet Magritte also seems to acknowledge that it is neither possible nor perhaps even desirable to live in this state of innocent wonder all the time. Indeed, in some of his later paintings, he seems to suggest that getting hoodwinked or duped by treacherous and not-so-treacherous images is, to some extent, inevitable. Consider, for instance, the following painting as well as its title.

As you can see, except for the thin strip of vertical white canvas, the landscape outside the window is virtually indistinguishable from the landscape painted on the canvas itself. Among other things, perhaps Magritte is suggesting that it is the human condition to confuse our images or symbolic representations of events (i.e. the canvas) with the actual events they represent (i.e. the landscape outside the window) to the point that we can barely distinguish which is which because we habitually collapse the distinction between the two. And this is perhaps Magritte’s way of reminding us that there are good grounds to give ourselves a break when we do, from time to time, get taken in by the treachery of images.

Exercise: “This Is Not a Pipe”

1) Get into a relatively comfortable position and, with eyes open or closed, pick an object to focus on, like your breathing, some sounds, a syllable, a phrase, a physical object, or a pleasant feeling.

2) Now simply concentrate on your object and resolve to maintain your focus on it.

3) Notice what images arise in the mind.

4) Notice when your mind tricks you into relating to an image as though it is real, as though it is the object or event it represents. Each time this happens, make a mental note to yourself: “This is not a ________________.” If, for example, the image of a pipe arises in your mind, say to yourself verbally or non-verbally, “This is not a pipe.” If the image of your mother’s drowned body arises in your mind, say to yourself, “This is not my mother’s drowned body.”

5) Once you have dis-identified from the image, or de-literalized it, remind yourself, “This is the human condition” and, with a lot of warmth and kindness, invite the attention back to whatever you have chosen to focus on in the here-and-now and, without trying, simply stay with the mystery and enigma of what is so. Freed momentarily from the “absurd mental habits that generally take the place of an authentic feeling of existence” allow your bare attention to “breathe new life into the way you look at ordinary things.”

References

Bennett-Goleman, Tara. 2001. Emotional Alchemy. New York: Three Rivers.

Scutenaire, Louis. 1982. René Magritte et le surréalisme en Belgique. Bruxelles: Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique.

Magritte, René. 1929. La Révolution Surréaliste. No.12, 15 Décembre.

Magritte, René. 2016. René Magritte: Selected Writings. Ed. Kathleen Rooney. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.