In May 2024, I delivered a presentation to the Swedish Bhutan Society and assembled friends in dance, anthropology, museum exhibition, ethnographic research, remote exploration, and the fine arts. The talk, “Mystical Dances in the Kingdom of Bhutan,” was in three parts. Part 1 appeared in September. Here I will share Part 2: “Cham Dance is Deity Yoga in Action,” and in December, the concluding section will appear.

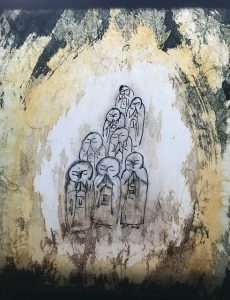

A masked shaman dancing in a trance to connect with a power from another plane of consciousness is one of the very oldest activities known to humans. The depiction of a dancing sorcerer is perhaps the most ancient image of a human. Dancing-induced divine interaction was depicted in art before hunting, fighting, or agriculture. In fact, masked dancing shamans appeared during a period of art depicting mostly animals. Along with abstract symbols.

Deity yoga in Vajrayana Buddhist monastic practice is the proper name for an elaborate sequential technique to self-generate oneself as a deity, and also to generate a deity sitting before oneself. It is abstracted, effective, and enriched through a thousand years of monastic practice. I understand it in ways parallel to the way the Catholic Church has enshrined the archaic practice of virgin worship in the refined and elegant image of the Virgin Mary. One issue that Protestants had with Catholics was the predominance of virgin worship.

I was raised in a Catholic home. My Mother was a devotee of the Virgin Mary. I know many sublime prayers, songs, poems, paintings, and sculptures about the Virgin Mary. Just beautiful. Indeed, the rosary—the source of the prayer, “Hail Mary”—is an exalted, effective, and widely adopted meditation technique. It remains true to its essence: veneration of the Virgin.

Vajrayana deity yoga is similarly a refined and widespread meditation technique that evolved from the most ancient acts of intentional mental transformation. Cham takes this base of realization and adds a layer of whole-body activity. This becomes a kind of ecstatic dance. A combination of ritual elements prepare the mind in an environment sympathetic to the sustained awareness of another dimension of consciousness. One’s identity as a human body sheds in the course of concentrating the mind, and directing the energies of the body toward an ever-more-essential level of personal continuity, from which the dancing deity emerges. There is a psychic trust, a trance, that the encounter with unknown energies—within and without—will provide wisdom benefiting people, however wild, daemonic, tantric, or primal the dance.

Here is a simplified outline of deity yoga as a Vajrayana practice:

1. Generating oneself as a deity

2. Generating a deity in front of oneself

3. Imagining a moon at the heart of the deity in front

4. Imagining the letters of the mantra to be repeated around the edge of that moon

5. Performing the deity mantra

In Vajrayana Buddhism, deity yoga is perhaps the fundamental defining practice of the monks. It is ancient, originating from Vajradhara, a primordial buddha inhabiting another dimension of existence. It is usually and mostly done sitting in meditation posture, legs folded. It is a difficult, highly technical kind of apex meditation, a culmination of years of gradual mental training. Of concern to anyone meditating is the matter of sustaining the state of mind, the freedom, indeed bliss, of recognizing the ephemerality of the world, the translucent emptiness of cyclic cosmic creativity. Deity yoga finally, like most advanced mystical practices, is about the simple and complete participation with consciousness itself.

The 12th century monastic dance treatise The Snow Lion’s Attributes is a treasure of the Drikung Kagyu monastic order. It details the purpose, history, and philosophy behind the cham dances. It states plainly: “Cham is the apotheosis of mystical attainment.” Cham takes everything that I’ve been writing about here—not as the conclusion, but as the base of the manifestation of the tantric deities.

Only those monks who have already achieved competency in deity yoga are permitted to become cham dancers. Cham is yoga, a danced yoga. Yoga, used here, simply means “meditation technique.” In some monasteries in India’s Spiti Valley, the dance master, or champon,must spend a year in solitary retreat meditating exclusively on one deity, before he can lead others in the dancing. The dance forms of cham are said to have originated with the founder of Buddhism in Tibet, the great wizard Padmasambhava, whose legend is connected with mystical dance traditions in Swat, Nepal, Bhutan, and Tibet. Dance provides order and structure to wild forces. Dance itself is an instinctive force—as any dancer knows—and has the power to completely transform the mind, becoming its own state of consciousness.

The Buddhist teaching says: “When the mind becomes the practice, this is deity yoga.” The cham dancer goes beyond this: the mind becomes the body; the body becomes the practice of insubstantiality, manifesting a dancing deity with whole-body intelligence. Awareness of a higher consciousness, coupled with skillful techniques of body and mind, result in the deities—and their virtuous powers—being given life for an appearance in this world; one that is sure to dissolve with the end of the ephemeral dance. Otherworldliness pervades the patterns of the dance, which, like any mandala, are portals of higher consciousness.

Dance is the most effective way to sustain a complex meditative state, but is not easy to do. In Nepalese Newar Buddhism, the word “dance” means meditation: the famous dancing-deity paintings are paintings of meditation. Monastic cham dances, especially those of the Drikung Kagyu order, are models of the mind, examples and instructions for meditation. In one particular Mang Cham of 36 dancers, the entire form of the mandala falls apart in lapses into chaos, the courtyard full of random individual movement. Then, through a process, the dancing mandala is re-formed.

There are practices used in cham performance that do not apply to seated deity yoga. First among these is the dance itself, the choreography, the endless repetition of mandala circles. It is difficult to express for how long the monks dance. Over a three-day ceremony, any given monk would have danced for at least 10 hours. There is rehearsal before the actual ceremony. There are many purposes and roles of the dance in cham. Foremost among them is the ability to sustain an exalted state of mind—deity yoga—as the deity moving himself in the manner of divine being: shining, proud, luminescent, beneficent, protective.

The basic activity of visualization meditation is the appearance of a vision within oneself, that becomes, after a time, the only object of consciousness, replacing the identity of a human body or the ego-based self. Then, the vision is let go, dissolved, and a state of emptiness and bliss results. Traditions of cham vary, but many teach the skill of expanding the deity within to become coextensive with their own physical body; so the human body is conceived as the deity’s. Then the monk is instructed to expand the deity beyond their own physical form, and “swim along with the deity.”

Performing cham also differs from seated deity yoga—which is a sequential, constructive activity—by using also the direct projection of a deity from mind-to-mind, which delivers the deity fully realized, apprehended in its totality. This mind-to-mind projection of images is a known skill in Buddhism. I have been the recipient of it a few times. Complex visions appear all at once. Even things that exist in time—such as a dance—in a split second can be apprehended in full. In Bhutan, during their great annual Thimphu Tsechu dance ceremony, the dancers’ final preparatory step before entering the courtyard, is the Je Khenpo himself, the patriarch of Buddhism in Bhutan, who—forehead to forehead—projects a deity visualization into the mind of each dancer, one by one, as they enter the dance ground. Now the dance can begin.

Cham is deity action. Riding the sound of mantra, performing mudra to activate energies, the mind becomes the body through dance, a humble monk becomes a shining protector, victorious in piercing through the illusory world. The 12th century treatise teaches the realization of “deity pride” of a protector deity: “Shake your head like a lion with prey in its mouth.” Cham destroys illusion. As my colleague of many years, Gerard Houghton, can attest, my reaction, when the last dancer exits, after a six-hour day of dancing, is always, “Don’t go!”

See more

Related features from BDG

Mystical Dances in the Kingdom of Bhutan, Part 1: A Black Magic Dance at the Core of Bhutan’s Founding

Mystical Dances in the Kingdom of Bhutan, Part 3: Treasure Dances, the Long Tradition of Mystically Revealed Tercham