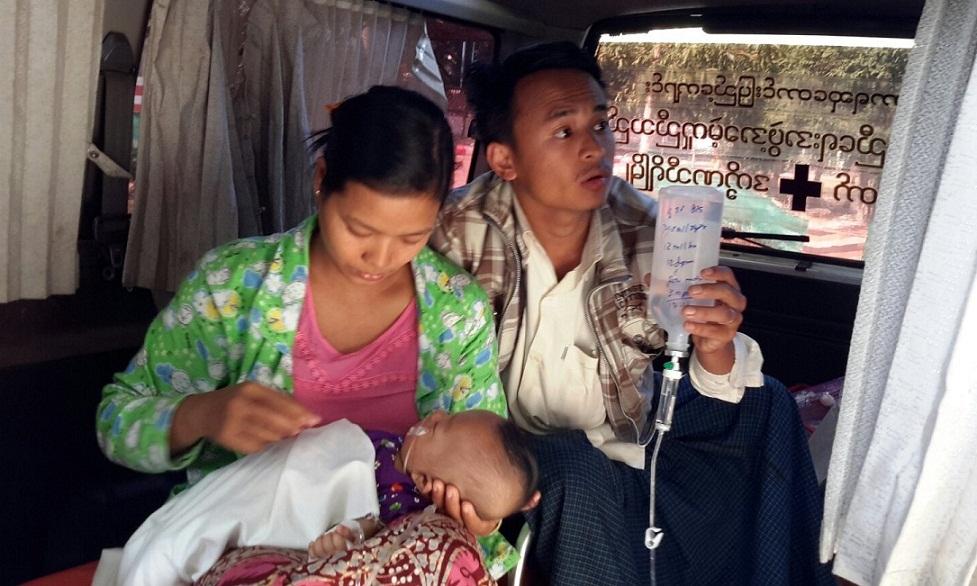

The ambulance pulls up at the gates of Htantabin Monastery in Myanmar’s capital, Naypyidaw, where Sayadaw Kaywala waits patiently. As the door opens, he bends to extend a comforting hand to the curled-up body lying on the stretcher. Ma Myi’s wrinkled face breaks into a gentle smile as she receives his blessings. Words of gratitude are unnecessary. A worker loads an oxygen cylinder into the ambulance and soon it is off, on a 250-kilometer journey to Ma Myi’s hometown, Pekon.

A used van that has been reconditioned and fitted with an old air-conditioner, a stretcher, a first aid box, some basic equipment, and a hook for a drip, this “ambulance” is doing her last laps, just like Ma Myi. With each bump and pothole on the rugged road, the old frame rattles from the worn-out suspension. For 70-year-old Ma Myi, diagnosed with blood cancer, it does not matter. All she wants is to be able to spend her last days with her children and grandchildren and to die in her own bed, at home. Were it not been for this old ambulance, Ma Myi would probably have had to spend her last days in hospital.

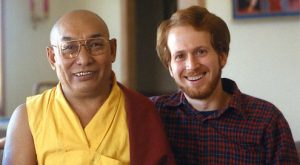

Sayadaw Kaywala, who is chief abbot of Htantabin Monastery, explains: “In Myanmar, many poor people who are sick have to travel long distances to reach health facilities, by carts, public buses, or boats. Even when they arrive, they may receive no treatment because of a shortage of medical equipment or staff. It is unbearable to see the elderly, the babies, and the handicapped having to endure such difficulties just to get medical treatment. With what the monastery could afford, we started this free ambulance service. The doctors have said Ma Myi’s case is hopeless, but at least she can have her last wishes fulfilled.”

the author

But Htantabin Monastery does not only provide for the needs of the living. There is also a “Nibbana van”—a term used in Myanmar for vehicles that deliver corpses. On average, the monastery delivers around ten corpses a month from the hospitals back to the deceased’s home villages, some as far away as the Myanmar-Thailand border. In Myanmar, where it is considered taboo to transport corpses, privately owned businesses charge exorbitant prices for such services. Even the government municipal service charges 50–80,000 kyats (10,000 kyats=US$8), with private hospitals demanding 100,000 to 500,000 kyats, all well beyond the means of most poor households. Funerals are also a financial burden—they can easily cost more than 20,000 kyats.

“How can a person with a daily income of 3,000 kyats afford all this?” the 56-year-old Sayadaw asks. “In our Burmese tradition, funeral rites are very important as it means the passing into another life. Most people prefer to conduct the funeral at their own home so the family, relatives, and friends can observe the wake. We not only perform the religious rites, but often help out with the funeral expenses so that they can have a dignified funeral ceremony.”

According to a World Bank report, in 2013 public health spending in Myanmar accounted for only 1.8 per cent of GDP, among the lowest in the world. Private, out-of-pocket health-related expenditure amounted to 68.2 per cent of the total, compared with only 27.2 per cent for public spending, or less than US$1 per person annually. With the low priority given to public health care, many essential services, including emergency care and the ambulance service, have been forced to take a back seat. Until 2012, at many public hospitals these did not even exist. With poor funding, public hospitals are also lacking in medical supplies, bedding, sanitary facilities, surgical instruments, equipment, and even doctors. As such, they have only been able to provide basic care. The burden of health care has thus fallen on the patient, via a cost-sharing system requiring them to pay for at least some of the equipment used during treatment. In a country where many live below the poverty line, the poor have often had to seek other options or forgo treatment altogether.

In 2010, Sayadaw Kaywala started a life-saving project to supply free oxygen cylinders to poor patients. In a room filled with cylinders, Sayadaw recounts: “Initially, the Oxygen Centre was only for the poor families who could not afford the treatment at the hospitals. Over the years, the number of patients coming to the hospitals in Naypyidaw has increased significantly. [So] the doctors approached us for help as there is not enough equipment. For example, the Naypyidaw General Hospital has 1,000 beds, but only about 20 oxygen units.”

Each month, Sayadaw Kaywala receives some 300 requests from the three hospitals in the area, and from around 15 home patients requiring palliative care. From 40 cylinders, the Oxygen Centre has expanded its operations to more than 200 three-foot and 100 six-foot cylinders, and is probably the largest center of its kind in Myanmar. Even so, it can barely meet the increasing demand. The cylinders are sent in batches each week to be refilled in Yangon, about 200 miles away. All the costs of operation and maintenance, refilling and transport, are borne by the monastery. In addition, there is the cost of retrieving the cylinders after use, sometimes from very remote locations. With no support from the government, the work is carried out by volunteers and funded by both local and foreign donors.

Over the last two years, as a result of increased government funding, Myanmar’s public health care has improved, albeit slowly. Since August 2014, emergency care and certain services such as some blood tests are provided free. For many, the possibility of a better future looks promising with the 2015 landslide victory by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy. But there is no miracle pill for development. After decades of stagnation and neglect, the country’s infrastructure is fragmented and decayed. For the poor in this Golden Land, the monasteries and monks remain the main source of support, not just for spiritual guidance, but for medical services, education, food, housing, and other needs. From free medical treatment to ambulance services, monasteries like Htantabin serve as the backbone of Myanmar’s ailing health service.

When asked if it would not be more practical to switch to oxygen concentrators, which are more compact and easier to operate, Sayadaw replies pragmatically: “Remember this is Myanmar. Many villages still do not have electricity. And where there is, it is sometimes on and sometimes off.” International human rights law can require governments to provide basic health care, education, and housing, but changes in Myanmar will take time. “When you are sick and dying, you cannot wait,” Sayadaw remarks. “The poor people have suffered unbearable hardship for a long time. If the monasteries don’t take the lead, they will suffer more. The monks and monasteries are filling the gaps that have been neglected by the government. The wealthier people can afford to go to neighboring countries like Singapore for treatment. Some even borrow money to escape across the border to Thailand to seek treatment. The poor who come to us are helpless and desperate. They have no other means. Most of them live on a hand-to-mouth basis daily. They have no savings, no insurance, and no welfare assistance. We cannot turn them away. It is not the Buddhist way.”

See more

2.15 World Development Indicators: Health Systems (The World Bank)