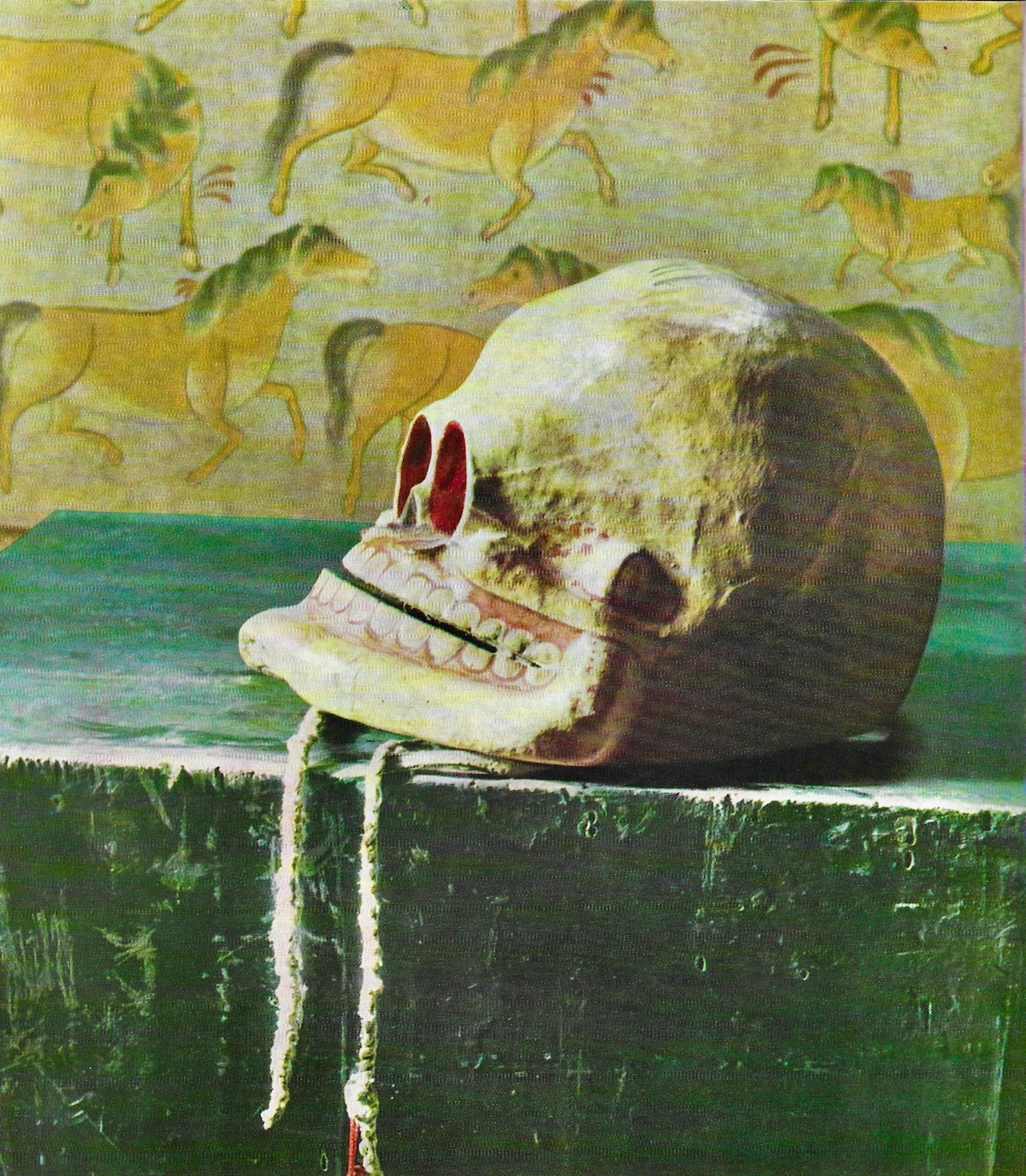

Image courtesy of the Werner Forman Archive

In 1691, Mongolia was subjugated by Qing dynasty China and remained so until 1911, when the Qing fell. Mongolia declared independence in 1921 and for a few years was led by the popular and powerful Bogd Khan (r. 1911–24). With his death in 1924, the Soviet Union achieved their goal of dominating Mongolia, establishing the People’s Republic of Mongolia in 1928. Soviet-style rule and Russian culture prevailed in Mongolia until 1991, when the Soviet Union fell. In 1992, a new constitution was written and the name “Mongolia” adopted. The first elected non-communist leaders appeared in 1993 and 1996. Mongolia is now a market economy and a major source of highly valued rare earth minerals used in manufacturing electronic devices.

From Core of Culture

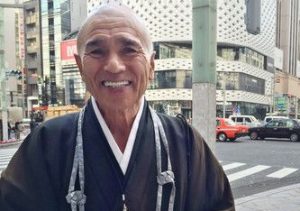

One characteristic of an ancient dance is that it has survived political change. Political change in Mongolia has been brutal. Buddhism was introduced into Mongolia in the late 16th century, and flowered during the Qing dynasty. By the early 19th century, nearly a third of all adult males in Mongolia were Buddhist monks. Today, no monastery in Ulaanbaatar has resident monks; they return to their homes at the end of each day. I was able to visit Mongolia in 2012, assisted by the able Arts Council of Mongolia. We gathered a representative group of dancers of all stripes, including monks and ballerinas, to gain a grasp of the fundamental dance ecology of contemporary Mongolia. Much has changed in Mongolia since 2012, but the basic factors at work affecting dance traditions and professions remain at play.

Buddhist ritual dance is not in a healthy state in Mongolia, and there are reasons why this is so and factors that can be explained. It is a surprising fact that all of the former Soviet satellite countries, including the Islamic “stan” states, have glorious opera houses, ballet companies, opera companies, and symphony orchestras. The State Opera House in Ulaanbaatar is beautiful, with a Mongolian mandala motif on the domed ceiling. Sergelen Bold, a ballet star trained in Perm, who made a name for herself portraying Giselle, was the director of the State Ballet in 2012. Like so many other ballet companies in the world, it was running on a shoestring. She explained how people love ballet, and numerous ballets with Mongolian themes have been produced over the decades. She told me how the opera and ballet were events where important people gathered. I saw a Mongolian-themed ballet and opera. The style of ballet is reminiscent of Russian dancing in the 1970s. It has an archaic quality.

Photo by Werner Forman.

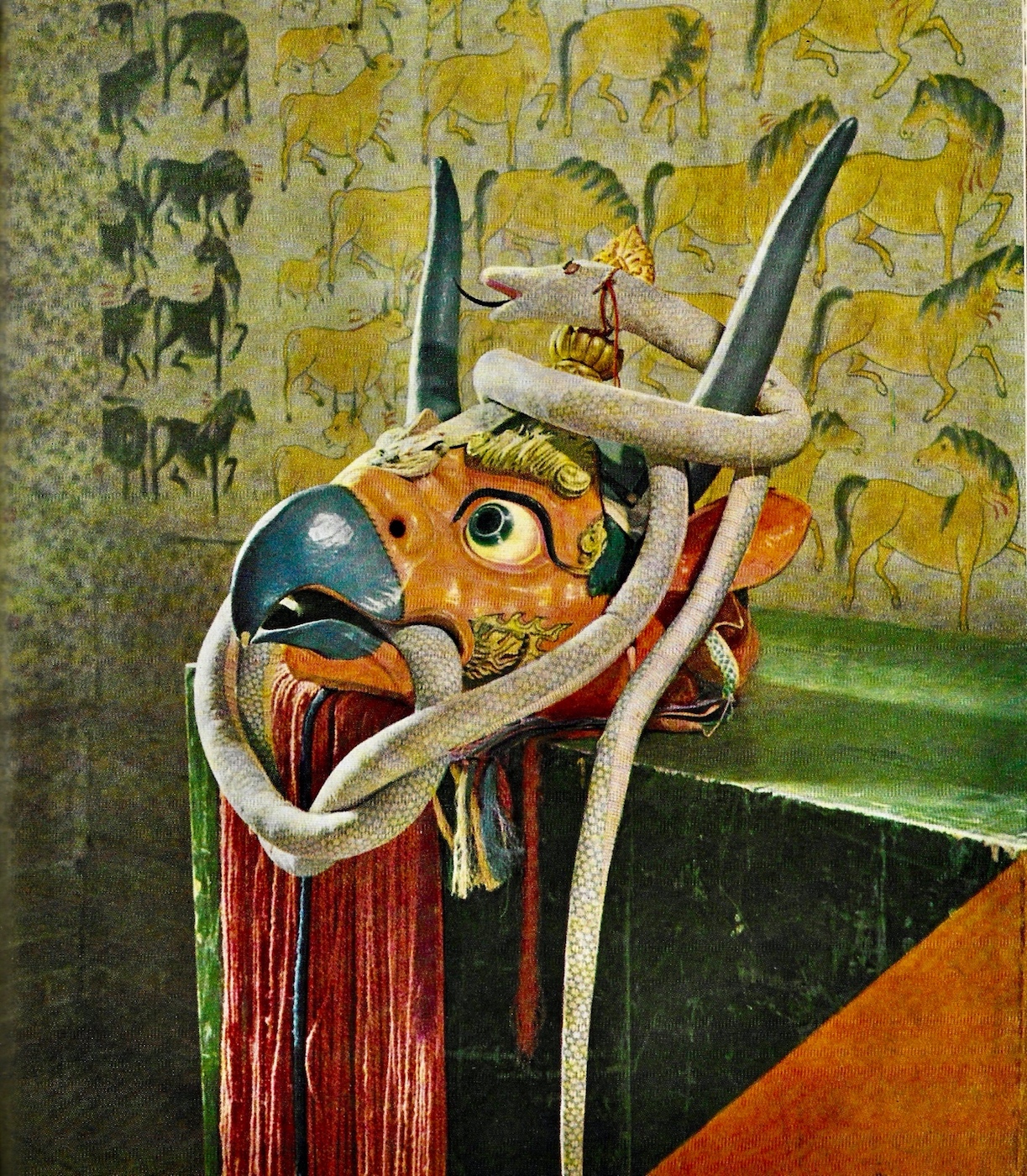

Image courtesy of the Werner Forman Archive

With ballet comes professionalism. During the Soviet decades, a robust business in theatrical shows, including dance, produced a class of highly trained professional dancers who could perform Mongolian folk dance, old court dances, and nomadic dances. And they could perform new dances. Tumen Ek is the pre-eminent traditional theatrical troupe in Mongolia. They are a living encyclopedia of Mongolian dances. As China and Russia also do, Mongolia teaches ballet to its professional folk dancers, resulting in “folk” dance that looks perfect, faces front, and also looks like like it is performed by ballet dancers, not villagers. Tumen Ek is a wonderful company. Thoroughly professional, precise choreographies and talented dancers. Mongolians, as a people, are very good dancers.

Tumen Ek is regularly involved in dance research projects. One important project, funded by a Dutch ballerina, documented dances in a remote nomadic area for the purpose of Tumen Ek learning these dances. The troupe is in fact a type of living repository of dances. Most dance research is recorded in books, some now in video.

Image courtesy of the Werner Forman Archive

It is a sign of the times that Mongolian ballet-trained professional folk dancers do a nomadic dance on a proscenium stage for a commercial performance. The nomads whose dance this is must have been honored that the most famous troupe in the country was coming to learn their dance! In the 1990s, when the monks desired to revive their tsam (Tib: cham) dances, it was the sad state that there had been no dancing for more than two generations and no one knew how to dance at all, much less how to properly perform ritual tsam. So the monks enlisted the professionals to help them learn how to dance and, beyond that, how to re-learn their tsam dances. As a result, the professionals learned the tsam dances.

Few things are so spectacular as tsam. Mongolian Buddhists transformed tsam’s characters, mask size and expression, costume elaboration, and pageantry, reflecting their nomadic roots and large outdoor celebrations. What could be better as the finale for a commercial theatrical folk dance performance than a spectacular tsam number before everyone goes home? The professionals began adding tsam to their roster of dances in commercial shows, using correct masks and costumes, and sometimes using ritual steps and sometimes using completely new choreography for the show. The Tumen Ek performance I attended ended with a dramatic tsam number, the country’s gods appearing at the end to give a blessing, facing front, not in a circle as tsam is traditionally performed. The Tsam number followed a female contortionist in a full-body unitard.

Image courtesy of the Werner Forman Archive

Buddhist monks, who no longer have political power or wealth, cannot compete, even in the realm of producing costumes and masks. In fact, the professional company Tumen Ek is doing the country a service by archiving, researching, and performing Mongolian dances. Dashi Choeling, a large monastery within Ulaanbaatar, years ago allowed a circus to use a part of their compound. It has never been returned to them. Mongolian tsam is well known for a large dance with 108 dancers. This is an enormous production to revive. In the 2000s, a tour operator who also brokered museum exhibitions on Mongolia, produced his own version of the 108 dancer tsam. There were impressive costumes, but people from all walks of life were enlisted to fulfill the 108 roles, neither monks nor professional dancers. Yet, in some way, the 108 dancer tsam had been reconstructed. The monks were not happy about it, even as other monks advised the production. It was not a religious ritual ceremony. It was the performance of a masquerade.

The monks would like the performance of tsam by professionals to stop, primarily because it tells a wrong story of tsam; it misuses tsam and confuses people about what the art form really is. Having a circus ensconced in a monastic courtyard does little to clarify matters. Painter Urdiingin Yadamsuren, who, from 1965–75, recorded in painting all of the 108 Mongolian tsam dance figures, made this astute observation: “The described performance is a religious ceremony but it has traditional, masquerade, and dance-art meaning.”

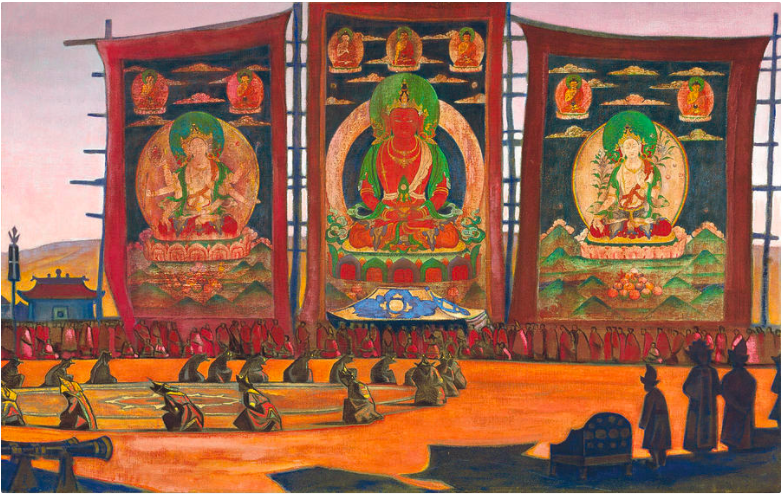

Image courtesy of the Institute of the Roerichs, Moscow

The spectacular nature of Mongolian tsam is on display in the Zanabazar Fine Arts Museum, where four life-sized models of tsam dancers tower over a display that includes four colossal embroidered thangkas, which are displayed outdoors and on monastery walls during tsam ceremonies. In the Chojin Lama Museum, which features temples in the Chinese, Tibetan, and Mongolian styles, one temple is full of tsam masks, and images of Black Hat dancers adorn the ceiling. Scholars at Mongolia’s Arts University research tsam from a textual basis of Soviet-style higher education, and so without knowledge of true religious tsam history and practice.

A fine account of Mongolian Buddhist tsam masks is a beautiful book by the indomitable German anthropologist Werner Forman, Lamaistische Tanzmasken: Der Erlik-Tsam in der Mongolei with Jamba Rintshcen, published in Leipzig in 1967. It is available online for a reasonable price. I cannot read German so I miss out what Forman has to say, within the larger context of performed, transformed, debased, painted, and marketed iterations of Mongolian tsam. Like the nation’s painter Urjingiin Yadamsuren, Forman conducted his artistic ethnography in the Soviet era, making it all the more meaningful to preservation. Forman’s photography and personal lens admiring tribal cultural expression make the photographs artifacts in themselves. This article features a number of photographs from Forman’s book used with permission from the Werner Forman Archive.

Image courtesy of the Werner Forman Archive

There remains a Buddhist monastic yogic dance in Mongolia, just barely. Tsam appears to exist in other ways in Mongolia, and in part what is seen is what happens when a dance is popular, and has artistic features that outlive its religious function. Hawaiian Hula dance similarly has multiple manifestations apart from its original role as a sacred act.

With special thanks to the Werner Forman Archive. Images taken from Lamaistische Tanzmasken: Der Erlik-Tsam in der Mongolei by Werner Forman and Bjamba Rintschen. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig. 1967.

See more