How disappointed are we in old age when joints just don’t move as easily as they used to? How about when the body refuses to obey us when we are ill or bedridden? How often have we vented, “My body isn’t listening to me!” to express our disappointment and often our deep and intense fear about our bodies?

Such innocuous, common phrases are symptoms of a more basic misunderstanding. Just like the illusion of the self, the true story is often counter-intuitive. Our minds are not detached pilots of our bodies, like drivers in deteriorating cars. To enjoy a broader vision of healing and leave behind the fear and frustration when our bodies are in pain or damaged, a more holistic approach is required.

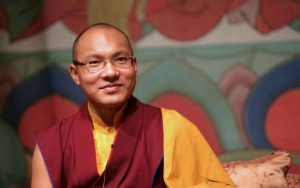

Venerable Analayo, who teaches at the Numata Center for Buddhist Studies at the University of Hamburg, has examined Buddhist ideas on healing by studying the early Buddhist texts, and from 1–2 July 2014, he presented his findings at a conference at the University of Leeds. The conference’s aim was to propose a new and more satisfactory model of the mind-body relationship, and to articulate a vision of healing that could transcend the notorious mind-body dualism that has plagued Western thought since Plato.

What one could call Cartesian (or more technically, substance) dualism—the idea that mind is separate from body—is a multidisciplinary problem that has spanned philosophy, counseling, pastoral care, psychology, and the medical field. Because of its immense influence on generations of thinkers, substance dualism is entrenched in popular discourse. Despite alternative models in Western philosophy that date back even earlier than René Descartes, substance dualism is the dominant mode via which we speak about ourselves. The idea that the mind is somehow disembodied and detached from the actual function of the body has become intuitive in Western society.

“The possibility of approaching the mind and body relationship without conceiving of them in a dualistic mode is in itself a very enriching notion,” says Ven. Analayo. “The very existence of this alternative in Buddhist thought and tradition can facilitate critical reflection on the advantages and disadvantages of positing the two as a dichotomy, as in the West we are often used to doing.”

When Ven. Analayo first encountered Buddhism and discovered that this dichotomy was not there, the impact on his thinking and practice was significant. “A discourse in the fourth of the five collections in the Sutta Pitaka, the Anguttara Nikaya [AN 4.157], reports the Buddha distinguishing between those who are physically healthy and those who are mentally without disease, concluding that the latter are much more difficult to find. In a way, then, health in its supreme sense is reached with full awakening,” he adds.

“Another lovely passage that addresses the Five Aggregates comes up right away at the beginning of the Samyutta Nikaya [SN 22.1]. An elderly lay follower receives the advice from the Buddha: ‘Although the body may be sick, the mind should not be sick.’ This neatly sums up the Buddhist attitude towards disease, namely avoiding what leads to mental affliction.” Ven. Analayo often recalls this phrase when experiencing health problems himself.

“According to the central doctrine of dependent arising, a division is made between consciousness on the one side and name-and-form on the other,” he continues. “Here, ‘name-and-form’ stands for the body together with ‘name’ as the active parts of the mind that are responsible for our ability to name things [these are feeling, perception, volition, contact, and attention]. This much should already suffice to say that a body-mind dichotomy is not a Buddhist concept.”

“The need to take care of the body is a recurrent theme in the discourses and the Vinaya. Walking meditation, for example, is recommended for good digestion. But the spotlight is on mental health, and this is crucial not only from a soteriological perspective, but even of considerable importance when we are sick. Mindfulness itself has a healing property,” advises Ven. Analayo. “Suppose I have an accident and some of my bones are broken—of course I will try to get professional medical help to set them so that they can heal. But the entire healing process will go better if I am able to handle the situation with mindfulness and patience, perhaps thinking of loving kindness. So I don’t think it is helpful to posit a black-and-white contrast between medical and mental healing. Both have their proper place and are best employed in wise co-operation, as the situation demands.”

Ven. Analayo’s counsel about metta (loving kindness) and the transformative powers of spiritual practice reflects the ongoing integration of mindfulness and neuropsychology into Western culture, including corporate workplaces.

Western religion or theism, with its soul and resurrection doctrines, is sometimes seen as a co-conspirator in the mind-body dualism narrative. But in my encounters with pastoral theology and chaplaincy during my university years in the late 2000s, I noticed a marked shift away from the mind-body dichotomy (which dominates Western thinking, often regardless of religious affiliation). This shift is gradual, but from what I’ve seen in the pastoral care models of different faiths, the patient or client is taught to work in harmony with their body, allowing the distinction between body and mind to dissolve rather than seeing the body as something “other,” to be mastered or rebuked. By moving away from the framing of terminal illness or old age as a conflict against the “person” and his or her failing body (for example, leaving behind the combative, victory-or-defeat language of “losing the battle against cancer” or “succumbed to old age”), the client is able to cultivate nonattachment to the body while at the same time making peace with their physical afflictions without giving in to resentment, fear, or anger.

The doctrinal understanding of mind in the Buddhist traditions is counter-intuitive and requires meditative insight to grasp fully. Even then, there are unanswered questions. If the mind-body dichotomy is an illusion or a false reification, how long will it take Western culture to let go of it? And will Buddhism have any influence at all on this cultural shift in the West (for all we know, it might end up as a mere bystander)?

“Personally, I let go of this concept very quickly,” says Ven. Analayo, smiling. “How long it will take in general terms is hard to gauge. But however long it takes, I do believe that Buddhist thought has the potential to make a very active contribution to this cultural shift.”

Most major religions do not dispute the entirety of the contemporary medical system (although genetic engineering is an exciting frontier of debate), but merely suggest that it should be integrated with the individual’s spiritual needs. For millennia, it was common for devotees across Asia to approach a Buddhist shrine to pray for robust health. Often, these appeals were made to the Medicine Buddha of the Eastern Paradise, Bhaishajyaguru. Buddhism teaches that the body must be nourished and cared for because it is the fleshly vehicle we use to reach liberation. However, the true power of Bhaishajyaguru is to cure worshippers of the Three Poisons, namely greed, hatred, and delusion. The highest form of healing is thus the transformation of the mind.

For more information, see:

UK Association for Buddhist Studies Conference 2014: Buddhism and Healing