Even the most secular-minded practitioner of mindfulness will be affected by this ritualized time of the year that is Christmas. It evokes childhood memories and family customs and there are choices to be made—you could spend it in a fog of general overconsumption or you could find ways to stay clear, conscious, and connected and actually enjoy it more.

I wrote my PhD thesis on ritual—many years ago—and my curiosity in this area has persisted. The title of my thesis was “Gestures towards emptiness: an exploration of ritual with reference to Buddhist tradition and innovation.” Shortly after starting this arts-based research, I got hit by type 1 diabetes, the start of a lifetime of injecting insulin. I became interested in the ritualized elements of diabetes management, particularly pricking my fingers up to ten times a day to take readings of my blood sugar levels. I made artwork using handmade paper as blotting paper for the remaining blood on my fingertips.

The phenomenon of repetition, one of the hallmarks of ritual, grew into one of my enduring fascinations. Repetition reassures us on a visceral level of our place in an ordered universe. Doing the same thing at the same time, like the first cup of tea in the morning, puts the world right. This could either be a largely unconscious act, keeping us in automatic mode, or it could be the cue for waking up into a more sensory and alive presence. How does the tea actually taste this morning? Mindfulness fights the dulling aspects of repetition while using it as the structural bedrock for regular practice that liberates insight and creativity.

“Mindfulness isn’t difficult; we just need to remember to do it,” Sharon Salzberg famously said. We forget, again and again, but slowly our brains rewire and we are able to stay present more of the time. Life appears in brighter colors and sharper outlines and we feel more intimately connected with it. So we do our best to remember. More recently I resolved again to take the pricking of my finger as an opportunity to drop into more heart-based awareness, thus using a daily and often wearisome reoccurrence to my advantage.

During my training as a mindfulness teacher, the question of ritual was raised; the trainer was quite adamant that there was no place for ritual in secular mindfulness. What she may have meant was that there is no collective recitation of articles of faith, no chanting of hymns or mantras, and no wearing of special garments signifying ecclesiastical hierarchies. But for a sharing at the end of the course we were asked to bring an object that symbolized our inspiration for living mindfully. We sat in a circle around a central arrangement of flowers, rocks and lit candles. One by one, we talked about our aspirations and then placed our own little stones, photos, alarm clocks, etc. into the mandala. A poem was read. In the ensuing silence there was a palpable sense of significance and connection.

Rituals are a brilliant vehicle for discovering and celebrating our values, thus keeping them alive and consciously operational in everyday living. They are also a direct and powerful way to strengthen a sense of belonging and community. It would be very hard to maintain connection with one’s values without at least occasionally being mirrored by like-minded people. I think that rituals are therefore going to play a significant part in the flourishing of the mindfulness movement, and it will be interesting to see what shapes they will take. I am part of a small group of people, mainly former students of mine, who meet weekly for meditation and take turns offering some light facilitation. The meditation usually leads into some verbal sharing, with a lovely sense of spaciousness and deep listening. Not a meeting passes where there isn’t some expression of appreciation and gratitude for what we are doing. Is this just a habit or edging towards ritual? The traditional chanting of the “refuges,” which is part of Buddhist meetings, has the same purpose—it is essentially a way of acknowledging the value of the meeting and to ensure its continuity.

Rituals are a brilliant vehicle for discovering and celebrating our values, thus keeping them alive and consciously operational in everyday living. They are also a direct and powerful way to strengthen a sense of belonging and community. It would be very hard to maintain connection with one’s values without at least occasionally being mirrored by like-minded people. I think that rituals are therefore going to play a significant part in the flourishing of the mindfulness movement, and it will be interesting to see what shapes they will take. I am part of a small group of people, mainly former students of mine, who meet weekly for meditation and take turns offering some light facilitation. The meditation usually leads into some verbal sharing, with a lovely sense of spaciousness and deep listening. Not a meeting passes where there isn’t some expression of appreciation and gratitude for what we are doing. Is this just a habit or edging towards ritual? The traditional chanting of the “refuges,” which is part of Buddhist meetings, has the same purpose—it is essentially a way of acknowledging the value of the meeting and to ensure its continuity.

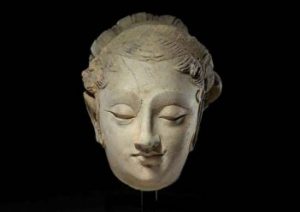

The festive period may or may not provide suitable conditions to clarify and celebrate our values as mindfulness practitioners. Christmas has many functions: it is a holiday, an opportunity to strengthen bonds with family and friends, a religious festival, or a retail opportunity. On a mythical level it is similar to ancient solstice rituals, celebrating light and new life. The birth of a child connects us with hope during the darkest period of the year—it reminds us that there are beginnings inherent in endings. Human beings have arrived at such understandings about life and death with or without religion. One of the central tenets—if that is the right word—of the mindfulness movement is that by embracing our inevitable pain and fears, we create the conditions for the arising of well-being. Dark inner states of mind can shift: when we live mindfully, we will eventually enjoy new-born, shining, infectious inner gladness and joy.

There is a well-researched link between happiness and meaning. The merriness of your Christmas depends on how close to your deeper values you steer. Rich food, alcohol, and extravagant presents probably don’t quite hit the spot for most people, if they are honest. The season can throw meaninglessness, old psychological wounds or family conflicts into stark relief, and it can all feel like hard work. And being alone at this time can be equally, if not more, challenging. It is emotionally draining to try to be merry when, underneath the jokes, we sense unhappy voices from the past, aching to be heard.

Here is a little gift for you: a 10 min guided meditation on “Adoring the Inner Baby.” May it contribute to enjoying a mindful and kind, and therefore truly “Merry Christmas.”

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

A Time of Giving: A Christmas Meditation on Generosity for Buddhists

Metta’s First Follower

From Vesak to Solstice: Connecting Through Festival

You Can Change the Past: Using Active Mindfulness to Rescript Difficult Memories