Welcome, dear readers, to another month of taking metta off the meditation cushion and out into the world.

April’s showers found me goat-sitting for a young family with a nod to the world’s most famous fictional nanny: Metta Poppins. May’s flowers found me growing organic produce for a market garden supplying subscription veg bags, as well as local restaurants and a weekly farmers’ market stall.

I dropped off my leopard-print suitcase—my 21st century Mary Poppins carpetbag, as I regularly change my spots—in the static caravan where I would be staying, and immediately changed into what I fondly call my play clothes. Back in primary school, we had a second set of outside clothes so we didn’t have to worry about getting our good clothes dirty during playtime.

It was a sunny nearly-summer’s day, and the team I was joining were busy planting seedlings. The seedlings had been sown from seed a few weeks’ prior, propagated in the polytunnel, and then hardened off outside on rows of wooden pallets. It was time to get them into the ground to grow fully and ready to harvest.

Watching the team run a tape measure along a 20-meter zero-dig bed—one of dozens in regimented rows over several hectares—and checking crop plans on their devices, muttering various measurements to each other along the lines of, “Four rows with a 30-centimeter gap for this one, no sorry, a 25-centimeter gap between plants but 30 centimeters between rows, staggered, one cell only, rake the wood chips back onto the path first, mix in some manure, and make sure to use the dowels to plough the rows first so they don’t go off-line and follow the drip hoses. Then lance them in, and mesh them over,” sounded like a foreign language to me.

And it looked even more foreign, like all the crop farming I had experienced so far during my year of volunteering on organic farms shrunken down to maximize space, diversity, and nutrition, and all the gardening I’d ever done blown up to minimize maintenance, interference, and effort.

Our first lunch break together gave me some indication of the new agricultural planet I had landed on. Market gardening appeared to be its own happy medium between large-scale farming and smaller-scale horticulture, and I later discovered that organic market gardening in particular only accounts for some 2 per cent of agriculture in the U.K. My first impression was of a very diverse group of people all working together to feed the soil and their community in more sustainable ways. In conversation, it emerged how many had attended some form of Steiner education and/or practiced biodynamic agriculture—one of the first forms of modern organic farming.

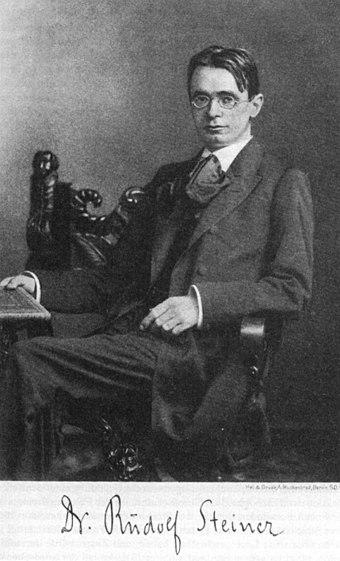

If the name Rudolf Steiner is new to you, he was an Austrian social reformer who founded an esoteric spiritual movement called anthroposophy at the start of the 20th century. This gave rise to an education movement, known as Steiner or Waldorf schools, an agriculture movement, known as biodynamics, a medical and beauty product company, known as Weleda, and a social care movement, known as Camphill communities for children and adults with developmental disabilities.

Attending my first formal team meeting gave me another indication of the new workplace planet I had landed on. After an update that the neighboring micro-dairy was struggling financially and about the pressures that the young woman managing it found herself under, we were asked to help where we could. When I raised my hand to check what form that help could take having never met her, I was told simply, “Be as kind as you can.”

This was music to my metta meditator’s ears as well as to my bruised and battered volunteer’s heart. I had secretly wondered whether any form of organic farming was actually sustainable, rather than simply an extension of the unsustainable modern workplaces that seemed to both deplete its people and the planet by rating competition above cooperation.

Previous articles for this column over the past year have explored all the weird and wonderful motivations (other than an interest in organic farming) of the volunteers I was encountering. But I also had yet to come across a genuinely sustainable organic farm, one that was sustaining itself and the planet in cooperative ways.

Between us, dear readers, rather than wonderful new ways of living and working I had probably encountered more weird and sometimes downright wicked ways of living and working on this volunteering voyage of discovery: mental health struggles, addiction, illness, animal cruelty, domestic violence, debt, discrimination, burnout, and so on.

Some days, I secretly wondered whether I had simply swapped all the outdated ways of living and working in a city for all the outdated ways of living and working in the countryside, only with a prettier backdrop and a better tan!

Over the next few weeks, I mucked in as best I could, laughing at and learning from my almost hourly mistakes. The team patiently corrected me as I clumsily sowed tray after tray of seeds, watered tray after tray of seedlings, planted tray after tray of hardened off plants, hoed row after row of ripening crops, and harvested crate after crate of produce. The sheer scale and turnaround of the plots and polytunnels from one day to the next felt like a kaleidoscope quilt constantly rearranging its patchwork.

The satisfaction I felt bringing what was ready to eat to the local weekly farmers’ market stall surprised me as, strictly speaking, we hadn’t produced a finished product as most people would understand the idea, rather we had nurtured a natural process.

Other than as another pair of hands to help with the never-ending unseen steps from seed to belly, why was I actually here in particular and still volunteering in general? As I sat with these questions in meditation and held them in my heart and mind while working alongside the team, the first inner metta seeds were sown.

The daylight hours quickly lengthened and garden conversations quickly deepened in the approach to the summer solstice. It dawned on me that my predominantly female teammates had been made to feel either unwelcome or exploited or had inherited outdated problems entering into farming. And it turned out the land we were regenerating was both a former dairy and landfill site for all the earth excavated to construct the nearby town’s giant supermarket.

Listening to their experiences as a fellow woman nearly two decades older than most, it saddened me greatly that so-called glass ceilings were still growing strong, even in plastic polytunnels and under open skies! And yet many of the most inspiring coworkers I had met in the workplace and the most inspiring organic farmers I had met in the past year were in fact men.

Regular readers will know that while I generate metta for all the world’s problems, I also aspire to generate down to earth solutions. . . . Regenerative metta, if you will. As I sat with this sense of inner and outer depletion and gender paradox, and held them in my heart and mind while working alongside the team, the first inner metta seedlings germinated.

Learning the basic principles behind zero-dig, min till (minimum till) and biodynamic growing watered my inner metta seedlings. Essentially, I was learning how to first nourish the soil, which in turn nourished the produce, which in turn nourished the eaters, all by increasing non-interference and biodiversity, and by keeping the process as local as possible.

While I could write a year’s worth of articles on all the practical techniques I learned and the stirring conversations I had this May, what stood out and spoke to me most is a combination of the two: actual stirring.

When our head grower mentioned that her mentor meditated for pest control, such as slugs or rats, my metta meditator’s ears pricked up. And when her mentor arrived for one of his weekly visits with a wooden tripod to hang over a giant bucket containing water, compost, and a spoonful of biodynamic preparation, I watched in awe as he stirred so fast as to create a vortex in seconds first in one direction to break down the chaos of outdated ways of doing things and then in the other direction to build up a new order. I happily volunteered to “stir” these intentions for the whole site first thing opening up mornings and last thing closing down evenings.

Our head grower then sent me to a “stir” at the neighboring struggling micro-dairy, where we all sat in a circle each stirring our own bucket for an hour as the big drum they would normally use had sprung a leak. I went with an open mind, and came away convinced when, after the hour, the water definitely felt thicker, not unlike churning milk into butter.

We then chose different sections of the land to “brush”—that is, dip a brush into the water and flick it up to the sky so sunlight could shine through the droplets, and then quickly flick it across the earth in front of us to spread beneficial bacteria and good intentions across the land. Ideally, this is done in the late afternoon when biodynamics consider the earth to be inhaling, as opposed to exhaling in the morning.

The inner metta seeds sprouting their first seed leaves delighted in being brushed, undoing all that was no longer working and inviting in what might, as well as blessing and nourishing the soil and its microbiome to eventually bless and nourish our digestive microbiomes.

As with the market garden’s quick growth cycle, the inner metta harvest from that afternoon’s stir was ready for the next farmers’ market too.

Our head grower and I were busy serving customers when the energy vampire described in “Metta’s Long Corridor” reappeared from the most unsustainable placement I had encountered in my year of volunteering.

It was my first time seeing her since February, and I had since heard about and encountered several vulnerable souls she had predated and depleted over the years.

As she attempted her outdated form of (shit-) stirring with a seemingly gracious offer to take any unsold produce off our hands as a donation for her current crop of volunteers, I silently remembered all the seeds of chaos and scarcity she had sown during our time together.

Our head grower looked pointedly down at our nearly depleted market stall table with her growing smile, while I bit back a snigger that the only two remaining items for sale were bunches of fresh garlic.

Karma can be a bitch, but she’s also a poet.

And, so dear readers, whatever vortex of outdated chaos may be growing in your own lives just now, please trust that at any moment the stir can unexpectedly turn in a new direction with some compost, community, and a spoonful of metta.

Or, to metta-morphose, Bob Marley’s song “Stir It Up:”

Since I’ve got you on my mind

Now you are here

(stir it, stir it, stir it together)I said it’s so clear

To see what we could do, metta

Just me and youCome on and stir it up, little darlin’!

Stir it up, come on, metta!

Related features from BDG

Engaged Buddhism – Inspiring Food Justice Ventures

The Soul of Soil: A Portrait of Frith Farm

Ajahn Sucitto, Down to Earth

Dharma’s Garden – Nourishing the Local Community through Homesteading

On Slugs and Karma