Welcome back, dear readers, to another Living Metta experiment in taking metta off the meditation cushion and out into the world.

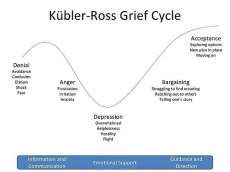

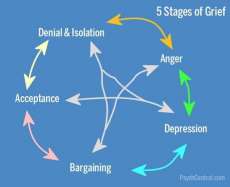

At the time of this writing, the collective grief process feels as though it has exhausted various stages of denial, sadness, bargaining, and arrived at full-blown anger. These psychological stages of grieving were first formally defined by a Swiss-American psychiatrist named Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in her 1969 book On Death and Dying.

During World War Two in her native Switzerland, Elisabeth helped refugees and later carried out relief work in Poland with the survivors of the Majdanek death camp. Listening to their stories planted the first of many seeds of what would become her life’s work.

During Elisabeth’s psychiatric residency in the US in the early 1960s, she noticed how terminally ill patients were often written-off by doctors and instead asked how they were coping with impending death. Those conversations surfaced patterns which eventually blossomed into a non-linear, five-stage model of the grief process: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

I first discovered Elisabeth’s work while watching black-and-white film footage of some of those interviews. How she held a space of genuine curiosity and compassion for each patient, who was otherwise being overlooked. was extraordinary. In my own life, Elisabeth’s acceptance of everyone’s ultimate uncertainty—death—helped me vto alidate my own and others’ feelings when nothing or no one else could.

Fast forward to 2020 to all the collective anger currently surfacing. Some reasons are obvious and others are anything but. Some expressions are justified and others are anything but. Some outcomes are peaceful and others are anything but.

In the microcosm of my daily life quarantining alone in Liverpool, collective anger took an unexpectedly criminal turn outside my window. In years to come when I’m asked how I spent the lockdown, my answer will probably be perfecting the art of police reporting.

It started innocently enough on the first evening of the UK’s official lockdown, with neighbors playing an impromptu game of twilight football in the street. I thought nothing of it until they started using where I live as their goal. The thump-thump-thump on the window got my attention, and I popped my head out the door expecting to have to ask the local kids to be more careful.

What I encountered instead was a group of unfamiliar young men in their 20s in a celebratory mood. Considering the shock and panic that most of my neighbors were feeling that night behind closed doors, it was confusing to be greeted with wide grins and wild shouts. I asked them to please move their goalpost, and they looked surprised to see me as no one else was daring to open their door anymore. It was a strange moment of dissonance between their mouths expressing apology and their body language expressing anything but. Something felt really off and in the following weeks I discovered why.

While most people and businesses were busy adapting their activities to the lockdown, so were criminals. While most people stayed behind locked doors, those looking for trouble suddenly found that they had the city streets to themselves.

From my front-row seat indoors to the quarantine circus coming to town outside, I watched the clowns escalate from football matches to water balloon fights, to scrambler bike meetups (unlicensed off-road motorcycles), to drug deals, to street parties, to street punch-ups.

I didn’t feel comfortable with the growing snitch culture baiting the public to inform on or shame anyone breaching COVID-19 guidelines (which weren’t actual laws but weekly shifting sands). My compromise? Hanging a “smile, you’re on CCTV” sign in the window to beware of the meditator bearing witness, and only calling in happenings that might land someone in hospital on the police’s non-emergency number. As the weeks went on, each conversation became more surreal than the one before: one evening the football was played riding scrambler bikes; another evening water balloons were thrown at the windscreens of oncoming long-haul trucks delivering food to the local shops overnight. Probably the funniest was trying to describe how two drunken street party guests were attempting to scale my opposite neighbor’s roof without a ladder.

I opened with, “I know we’re all climbing the walls these days, but. . .” The operator deadpanned: “So you’re saying that you’ve sighted actual Spider-men in the area?” I answered: “Exactly! Only they’ve been drinking in the Sun since midday, and haven’t realized their suction isn’t working.” We both laughed and said almost in unison, “This will not end well.”

It was easy enough to maintain equanimity and let the police handle any potentially serious incidents until three young boys I’d never seen before March were suddenly spending whole days in the street unsupervised, lapping up attention from the usual suspects. That triggered every kind of anger inside me watching the grooming slowly progress day after day. Like watching TV without the sound, I only had my Spidey-sense to rely on to pinpoint what to report as patrols always seemed to pass when all was quiet.

One evening, I heard gunfire outside. I ran to the window and saw the clowns shooting paintball air rifles at each other. My brain struggled to take in what my eyes were seeing: every parked car, house, and even the street itself were spattered in what looked like bird droppings. When they started aiming at the young boys playing, I drew my line in the shifting sands, and called 999 and anyone else I could think of at the city council, the housing associations, and social services. The reassuring news was that my reports weren’t the only ones and there were additional steps the city could try; the heartbreaking news was no one official could identify the young boys.

The following afternoon, there was an actual shooting in the street.

In complete contrast to the examples of police brutality in the media lately, dozens of officers and vehicles arrived on the scene to peacefully cordon off and canvas the street. I watched in awe from the window at how quickly they reclaimed control of the out-of-all-control situation. For 24 hours, five officers simply stood their ground within the cordon and later set up a mobile police station. No words. No movements. No aggression. It was a master class in the power of holding a collective space by being fully present.

While the mystery of the young boys remains, and the clowns still make an occasional guest appearance, the street remains relatively peaceful now. I looked out of my window the other day at the roof the Spider-men tried to scale three weeks previously and saw the most unbelievable sight of all: a teenage girl sat atop that same roof with her eyes closed in full lotus position. Beware of the meditator indeed!

Sadly, I can’t report the same for the rest of Liverpool this past month of easing lockdown, with dozens of daily shootings, stabbings, fires, robberies, domestic disputes, road traffic accidents, and drug busts. Some of those are to be expected in any city and some are due to criminals exploiting these unprecedented times. What saddens me most are the crimes committed due to people not knowing how to channel the anger stage of our collective grief process—and those manipulating that to their advantage.

Each time I hear a siren, a helicopter, or an (inner or outer) argument now, I remember the calm I witnessed during those 24 hours under police cordon and silently draw an inner line to hold a space for the acceptance stage for us all.

And so, my fellow metta-scientists, please do all you can this month to hold a space of genuine curiosity and compassion, as Elizabeth Kübler-Ross would, with whatever stage you—and the world outside your window—currently find yourself in.

See more

Dr Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s final appearance on Oprah (YouTube)